Scroll to:

Socioeconomic determinants of access to preventive healthcare services challenges and policy implications: A systematic review

https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2025-32-4-96-114

Abstract

Background. Socioeconomic determinants have a great influence on the access of preventive health care services.

Objective. The purpose of this systematic review is to assess barriers, facilitators, and policy implications for healthcare equity from the global data.

Methods. A systematic review was carried out across different regions and income classes. Data from studies regarding socioeconomic factors, healthcare system characteristics, and equity metrics were analysed. The statistical methodologies used were regression analyses, concentration indices, and inequality measures to measure the barriers and facilitators.

Results. The results suggested that financial constraints were the primary barrier to equity in low- and middle-income settings, supplemented by geographic inaccessibility and cultural factors. In the high-income settings, there were significant socioeconomic inequities despite the implementation of universal health coverage frameworks. The facilitators were universal health coverage, community-based interventions, and targeted reforms. Prominent trends of pro-rich utilization and gender disparities dominated, while equity-sensitive policies revealed success in closing healthcare gaps. Concentration indices had a significant inequity with moderate CI: 0.062 to high CI: 0.29.

Conclusion. The study shows multifaceted effects of socioeconomic determinants on access to health care, and there is a need for context-specific and equity-sensitive policies. There is a requirement to overcome financial and geographic barriers, improve health literacy, and integrate community-driven approaches in achieving universal healthcare accessibility.

Keywords

For citations:

Chaudhary Ch., Singh V., Singh S. Socioeconomic determinants of access to preventive healthcare services challenges and policy implications: A systematic review. Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2025;32(4):96-114. https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2025-32-4-96-114

INTRODUCTION

Role of Preventive Healthcare in Health Systems

Preventive healthcare services are one of the essential components of modern health care systems. They help to reduce the disease burden with proper identification of diseases, provision of appropriate intervention, and healthy behaviors [1]. Such services involve various measures such as screenings, vaccinations, health education, and lifestyle counseling. Some benefits that come along with such services include improved health status of the population and reduced health care expenditures [2]. The benefits have been well established; however, preventive care remains inaccessible, as it depends on multiple determinants like socioeconomic, geographic, and systemic determinants [3][4]. Such inequity prevents optimal effectiveness in the utilization of preventive approaches and escalates health inequities at both intra and inter population levels.

Socioeconomic Determinants and Access to Healthcare

Socioeconomic factors such as income, education, and employment determine access to preventive care services. People from a lower-income background are confined by financial issues, poor health literacy, and access to fewer health facilities, which prevent them from making use of preventive services [5]. In addition, geographic disparities face challenges, especially in the rural and remote settings where infrastructure and access to providers are inadequate. In low- and middle-income regions, the social determinants include gender, norms, and stigma, influencing healthcare-seeking behavior [6–8]. Together, they make up this complex set of barriers and hinder equal health care services.

Global Scenario on Preventive Healthcare Disparities

Globally, the distribution of preventive healthcare is characterized by striking inequalities that disproportionately affect low- and middle-income countries. These have been exacerbated by fragmented systems, resource constraints, and inadequate policies. High-income countries, with otherwise strong health systems, are also experiencing lack of access, primarily from socioeconomic stratification and work-related disparities [9–11]. All these measures, such as universal health coverage, community-based programs, and policy reforms oriented toward integrating preventive service delivery into primary healthcare, have varying degrees of effectiveness and much that is unexplained about the impact and constraint of these efforts in various contexts [12][13].

Need for Equity-Focused Policies and Interventions

Equity in preventive care access is a foundational means of achieving universal health coverage and, by extension, sustainable development goals. The multifaceted barriers require a holistic approach to bring together financial protection, infrastructure building, and culturally sensitive interventions [14]. All health systems must focus on catering to the needs of populations that are underserved: socioeconomic and geographic disadvantages are not acceptable reasons for depriving people of necessary service [7][12]. Systematic assessment and monitoring of equity-oriented policy interventions are also critical components to identify gaps and strengthen healthcare delivery [11]. This review, therefore, aims to systematically examine the influence of socioeconomic determinants on access to preventive healthcare services across diverse income settings, with the primary intention being that the analysis of barriers, facilitators, and equity considerations would shed light on critical insights into global disparities and offer evidence-based recommendations for policy and practice.

The aims of this systematic review is to assess barriers, facilitators, and policy implications for healthcare equity from the global data.

METHODS

Study Design and Hypotheses

This systematic review was based on the PRISMA reporting guidelines [15] and was designed to evaluate the effects of socioeconomic determinants on access to preventive healthcare services worldwide. It was hypothesized that lower SES, geographic barriers, and cultural factors significantly impede access to preventive healthcare. On the other hand, policies such as UHC and community-based interventions were hypothesized to reduce disparities. Both cross-sectional and cohort studies were considered to give a proper review of the current trend as well as the temporal association.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Peer-reviewed, cross-sectional, and cohort studies published in English were considered for review. Cross-sectional studies were chosen because they capture the snapshot of the disparities in access to healthcare, while cohort studies gave insights into the temporal and causal associations. Studies were included if they examined the association between socioeconomic determinants such as income, education, or employment and access to preventive healthcare services. Only those studies with clearly defined outcomes concerning utilization of preventive care were chosen. The rationale for focusing on cross-sectional and cohort studies was to ensure a robust quantitative analysis of trends and associations.

Exclusion Criteria

Excluded studies included interventional studies, qualitative studies, conference abstracts, and studies that had no adequate data on socioeconomic determinants or health care access.

Information sources

A systematic search was conducted across seven databases: PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, Embase, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, and ProQuest. The analysis of literature sources covered 10 years (from 2014 to 2024).

Search strategy

Boolean operators and MeSH keywords were used to create specific comprehensive search strategies for each of the databases. The selected terms were “socioeconomic determinants”, “health care access”, “preventive health care”, “disparities”, and “inequities”. Each database search string was modified considering the indexing system of the database to keep the sensitivity and specificity at optimal levels. Specific filters for cross-sectional and cohort studies were applied when available; only studies published in the English language were considered.

Selection process

The PECOS framework was constructed to systematically define the scope and inclusion criteria of the review:

- Population (P): All age groups from diverse socioeconomic backgrounds across high-, middle-, and low-income countries;

- Exposure (E): Socioeconomic determinants such as income, education, and employment;

- Comparison (C): Different socioeconomic strata or geographic locations;

- Outcome (O): Preventive health care service delivery, such as screening, vaccination, and health education;

- Study Design (S): Cross-sectional and cohort studies.

Data Extraction Process and Items Extracted

Data extraction was conducted using a structured and standardized template developed to ensure comprehensive and consistent collection of relevant information across studies. The protocol followed focused on extracting data on the following: study characteristics, demographics of the population, exposure variables, outcomes, and methodological details. The protocol followed in the data extraction process included the year of publication, country, income classification, study design, cross-sectional or cohort, sample size, and follow-up duration (where applicable). Population demographics captured mean or median ages, gender distribution, socioeconomic variables, and geographic location.

For exposure variables, all the socioeconomic determinants information was extracted in detail, like income levels, education status, employment types, and geographic disparities. The outcome variables included measures of access to preventive healthcare services, such as utilization rates of screenings, vaccinations, and health education programs. Barriers and facilitators to access, as reported by the studies, were documented to provide context to the findings. In addition, any equity considerations, such as pro-rich or pro-poor trends, were systematically recorded. Details about the methodology, including statistical analyses that had been conducted (e.g., regression models, concentration indices), and any controls or adjustments for confounding variables were noted. Where applicable, information on policy implications or recommendations was retrieved from the studies. Independent data extraction by two reviewers was conducted to avoid mistakes and bias, and differences in opinion were resolved by discussion or consultation with a third reviewer.

Study risk of bias assessment and Reporting bias assessment

For the evaluation of risk of bias in cohort studies, the ROBINS-I tool [16] was utilized while focusing on confounding, selection bias, and outcome measurement domains. For cross-sectional studies, the AXIS tool [17] was applied to assess study quality with regard to sample selection, data integrity, and objectives. Both tools were used by two independent reviewers, and disagreement between the two was discussed.

RESULTS

Study selection

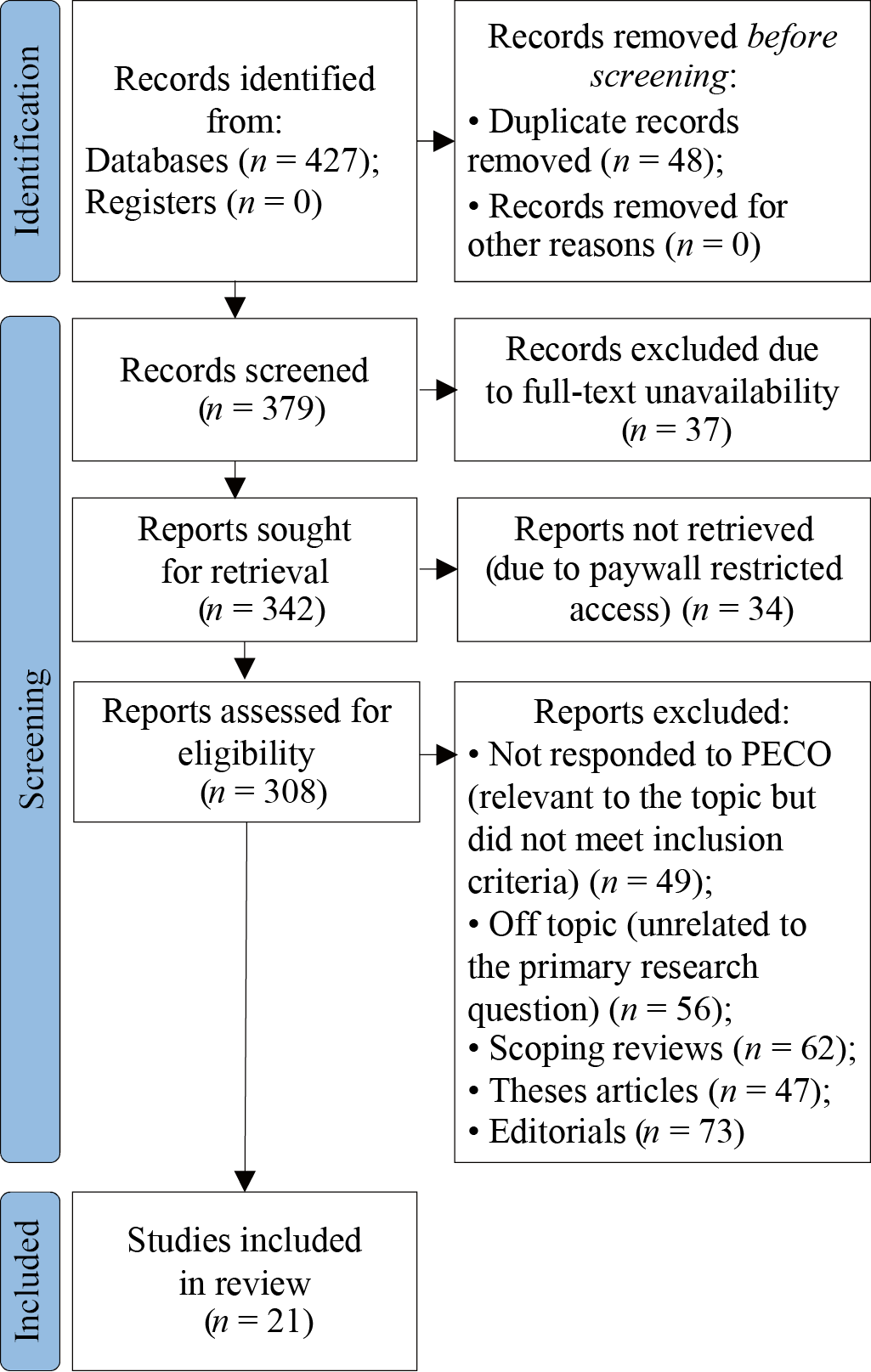

A total of 427 records were identified through database searches with no additional records from other sources. The removal of 48 duplicates left 379 to be screened. From the screening, 37 were excluded based on title and abstract. Then, full-text retrieval was sought for 342 reports, but only 34 were inaccessible because of access issues. In total, 308 reports underwent eligibility assessment. It was established that 287 were excluded, reasons for which were non-relevance to PECOS criteria (n = 80), failure to align with the main research question under investigation (n = 60), and other methodological issues (n = 147). A total of 21 studies [18–38] was included in the review.

Results of individual studies

Baseline variables assessed (Table 1)

The studies were spread across different geographic locations and populations, with large variability in sample sizes, study designs, and population demographics. Cohort studies, such as the Swedish study [18], had sample sizes of more than 126,000 epilepsy cases and controls, while much smaller cross-sectional studies, such as the one conducted in the USA [27], included only 108 participants. These differences point to different scopes of studies. Age distributions were also quite heterogeneous, with some studies targeting older populations, such as China [21], where participants aged 65+ were targeted, while others included broader age groups, such as South Korea [23], which covered workers aged 15+. Gender representation was also diverse, with studies from Germany [24] achieving near gender parity, contrasting with male-dominated samples, such as in Morocco [29], where 74.7% were male. The follow-up periods of the study further showed heterogeneity in methodologies. Register-based cohort studies like in Sweden [18] were 15 years, which allowed for longitudinal analysis, while most cross-sectional studies did not have follow-up periods, which limited the temporal inferences. These differences indicate methodological considerations that influence the depth and applicability of findings.

Socioeconomic Factors and Access to Healthcare (Table 2)

Income and education were the frequent factors determining access to healthcare. Brazil [20] and Mongolia [22] highlighted horizontal inequities where income inequalities really dominated usage rates. In studies from China [21] and Kenya [30], there was generally a split between urban-rural areas, which has proven to be a multiplicand of geography and poverty.

Barriers to Access to Health Care

Financial costs were another main hindrance among the studies. South Asia [33] and West Africa [34] have reported cost as a primary barrier of access to health service. Likewise, insecurity in employment also linked up to unmet healthcare need among South Koreans [23]. Geographical accessibility and the availability of a healthcare service were significant obstacles in such a distant location like Tibet [38].

Access Facilitators

Government policies and health care delivery systems were instrumental in reducing the barriers to access. Universal health coverage systems, as observed in Europe [25] and Australia [28], had a strong effect on the reduction of unmet needs for health care. Other interventions included community-based health interventions in Mali [34] and public health insurance schemes in China [38].

Outcome Measures

Most studies [24][26][28][35] often measured outcomes such as health care use or unmet needs. Examples include measurements of unmet surgical needs in slum populations in India [26] and health-related quality of life in Vietnam [35]. More subtle insights into policy effectiveness were obtained from measuring health inequalities by employing advanced statistical indices in Australia [28] and Germany [24].

Methods of Evaluation

Logistic regression models were commonly applied, such as in South Korea [23] and Kenya [30], to analyze factors determining unmet health-care needs. Concentration indices, applied in Mongolia [22] and Nepal [33], assessed horizontal inequity. The use of multilevel regression techniques helped break down individual and contextual factors determining health care access in some European studies [25]. These methodological differences underpin the different analytical intensity and purpose of the studies included.

Policy Implications

The results highlight the need for targeted health policies that focus on inequities. For instance, infrastructural development of public healthcare systems in low-income regions is recommended by African [19] and Asian [30] studies to reduce inequalities. Similarly, integrating financial services into healthcare delivery is envisioned to reduce socioeconomic barriers, as explored in North America [27]. The European [25] and Australian [28] studies have shown that universality is effective in reducing inequalities, and other regions can draw scalable models from them.

Barriers to Access (Table 3)

Barriers to access healthcare were multi-dimensional, and differed considerably by income category and health system characteristics. Low-income settings were characterized by pronounced financial and geographic barriers, and were observed in settings with fragmented systems and low availability of providers [22][31]. Rural populations faced compound challenges because of geographic inaccessibility and infrastructure deficits [38]. High-income settings also identified inequities, often in relation to SES, type of employment, and insurance status, where precarious employment was a common feature that resulted in unmet health needs despite universal healthcare arrangements [23]. Gender and cultural norms also worsened inequities in some settings, especially where traditional roles and beliefs restricted women's utilization of health services [29][34].

Health System Characteristics and Healthcare Provider Availability

Generally well-integrated, but with much variability in accessibility based on SES and regional disparities, most universal health care systems in developed economies are represented [18, 24]. Middle-income countries evidenced weaknesses in public-private integration and regional segmentation, allowing inefficiencies in resource utilization and poor services delivery [20][36]. In Low income settings, decentralized and/or fragmented systems were seen in shortages of skilled medical staff, especially for secondary and surgical services [31, 34]. Community-based health centers and traditional medicine practitioners were widespread in rural settings, but the quality of service was often low and services were not standardized [35].

Cultural and Behavioral Factors

Behavioral factors, including health literacy and stigma, were common in both low- and high-income countries. In lower-middle-income countries, stigma about disability [32] and epilepsy [18] resulted in delayed or avoided use of health services. Health literacy gaps were particularly pronounced in urban slums and among rural populations, further limiting access to available healthcare resources [19][29]. In high-income countries, self-perceived health needs and insurance complexity influenced healthcare-seeking behavior, particularly among the elderly [24, 28].

Facilitators to Access

Targeted policy interventions and health system reforms were facilitators. UHC and public insurance systems played a crucial role in reducing inequities, especially in high-income countries with established structures [18][25]. Community health workers and free essential medicines were instrumental in increasing access in lower-income settings, especially among rural and nomadic populations [34][38]. Incorporation of financial services into clinics for low-income populations was promising in reducing SES-based barriers in high-income countries [27].

Equity Considerations

Equity in healthcare utilization remained a major concern with continued disparities across SES, gender, and geographic divisions. Pro-rich and pro-urban utilization trends were observed in those countries with fragmented systems and a lack of public healthcare coverage [22][33]. In high-income countries, SES-sensitive policies reduced some disparities but were not enough to remove inequities [23][28]. Gender-sensitive reforms and focused interventions for marginalized groups brought positive effects in regions with strong disparities along gender and regional lines [29][36].

Long-term effects and policy implications (Table 4)

By income classification, long-run impacts of health policies were heterogeneous, whereas high-income regions with UHC frameworks in place showed better health outcomes together with reduced unmet needs even as SES-related disparities lingered, indicating a need to better fine-tune reforms [25][28]. Middle-income countries demonstrated evidence for targeted reforms, such as Brazil's Family Health Strategy, in reducing inequities and improving access in more vulnerable populations [20, 37]. Low-income areas experienced important implementation challenges that related primarily to workforce shortages and limitations in infrastructure, but community-based interventions did show promise in overcoming geographic and cultural barriers [34, 35].

Comparison across various regions revealed that decentralization and community engagement best suited low-income settings, whereas high-income countries relied on integrated systems with SES-sensitive policies. Middle-income transitional models tried to balance the problems of equity and efficiency through innovative supplementary insurance and localized interventions approaches [36][38].

Statistics

Various statistical methodologies were used in evaluating access and equity in health care. Logistic regression models and odds ratios dominated high-income and middle-income researches in the identification of predictors for unmet needs [23, 24]. Concentration indices and inequity measures, such as the Relative Index of Inequality (RII), were used to quantify disparities in both utilization and access across SES strata [22, 28]. Descriptive statistics and chi-squared tests were the most common analysis tools used in low-income settings to assess community-based interventions and regional inequities [3438].

Bias assessment observations

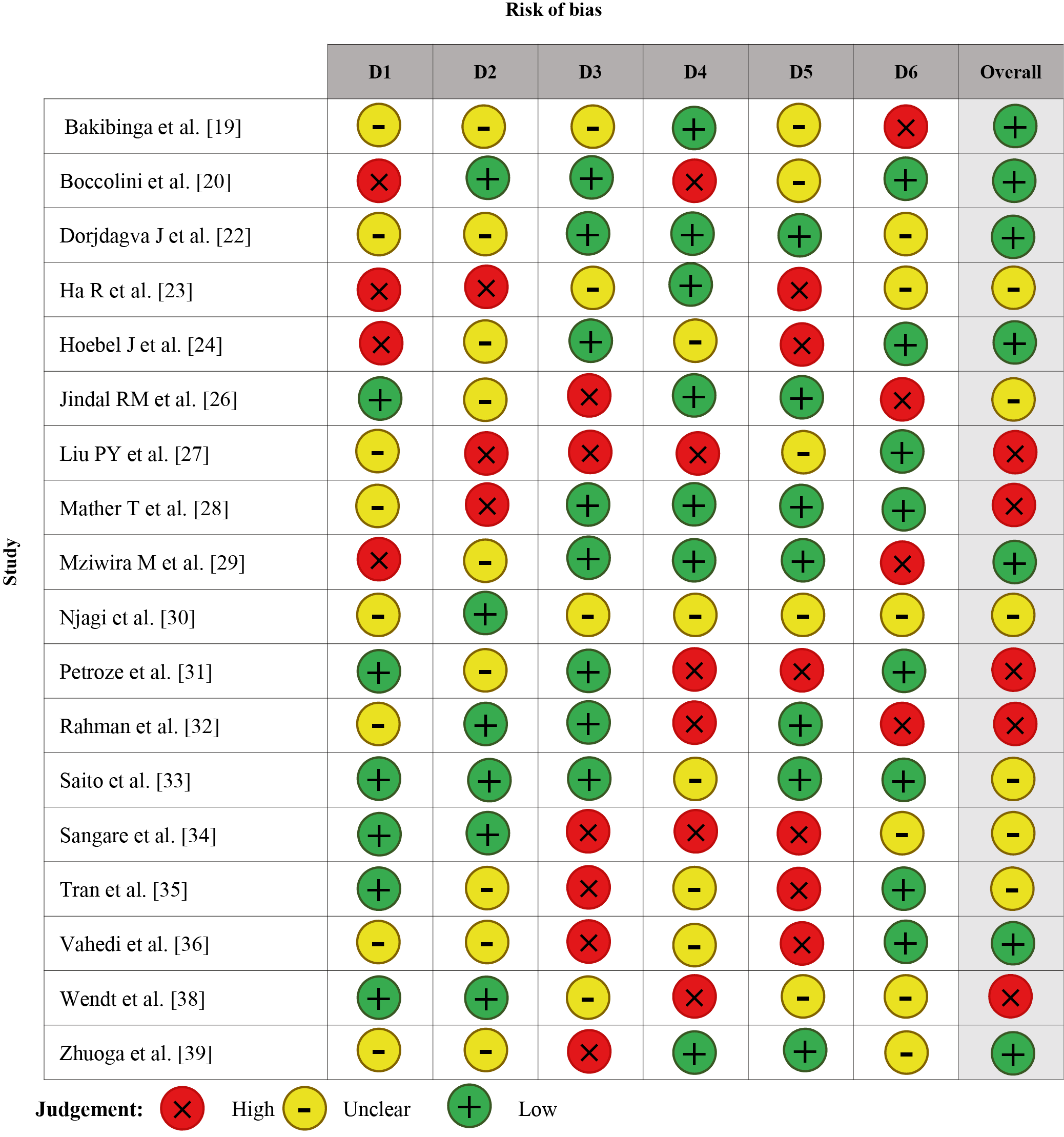

For the cross-sectional studies (Figure 2), Bakibinga et al. [19] demonstrated moderate selection, performance, and reporting biases with low overall bias. Serious or moderate biases were detected by Boccolini et al. [20] and Dorjdagva et al. [22] in individual domains but remained low overall bias. Ha et al. [23] and Hoebel et al. [24] had serious concerns with respect to multiple domains with the respective moderate and low overall bias. Jindal et al. [26], Njagi et al. [30], and Tran et al. [35] showed moderate bias in several domains, thereby having moderate overall risk. Other studies like Liu et al. [27] and Petroze et al. [31] have serious bias in the detection and attrition domains, leading to high overall bias. Sangare et al. [34], Vahedi et al. [36], and Wendt et al. [38] had moderate to serious detection and attrition biases, which gave rise to moderate to serious overall risks.

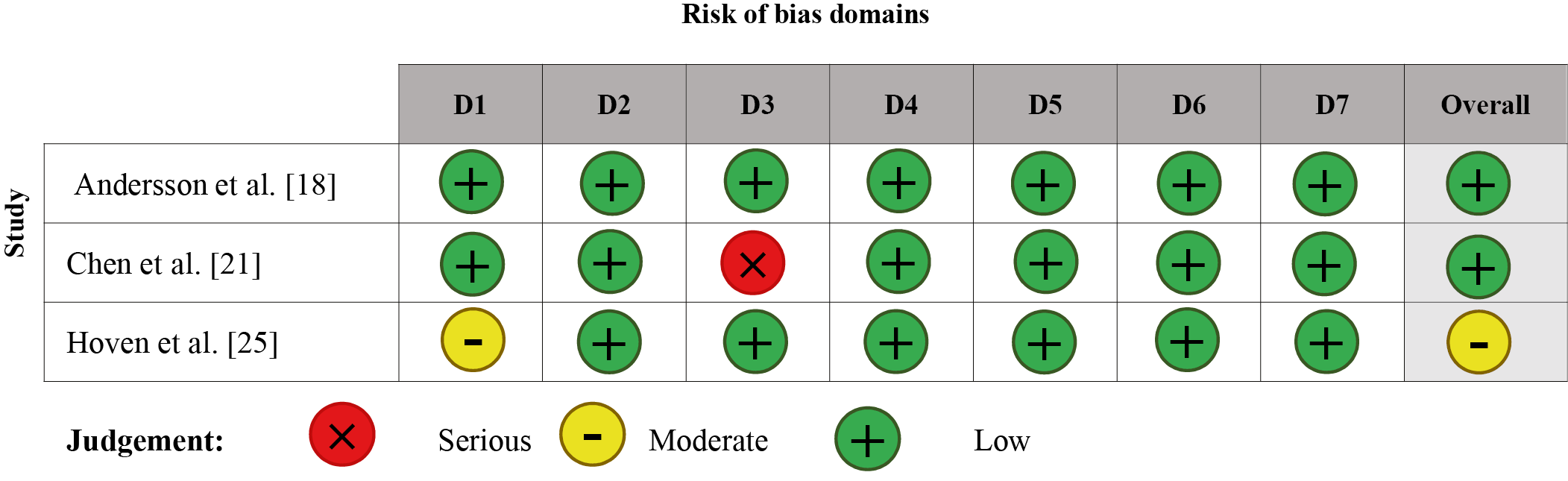

For the cohort studies (Figure 3), Andersson et al. [18] showed low bias in all domains with a low overall risk. Chen et al. [21] showed serious detection bias but retained a low overall bias because of minimal concerns in other domains. Hoven et al. [25] showed moderate selection bias but low bias in other domains, culminating in moderate overall bias.

Fig. 1. Description of the different stages of article selection process for the review

Note. The block diagram was created by the authors (as per PRISMA recommendations).

Рис. 1. Описание этапов отбора статей для проведения обзора

Примечание: блок-схема выполнена авторами (согласно рекомендациям PRISMA).

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of the included studies

Таблица 1. Исходные характеристики исследований, включенных в обзор

|

Study ID |

Year |

Location |

Study Design |

Sample Size |

Mean Age (in years) |

Male : Female Ratio |

Follow-up Period |

|

Andersson et al. [18] |

2020 |

Sweden |

Register-based cohort study |

126,406 epilepsy cases, 379,131 controls |

18+ years |

Matched for controls |

2000–2015 |

|

Bakibinga et al. [19] |

2021 |

Nigeria, Kenya, Bangladesh, Pakistan |

Cross-sectional |

7002 households, 6856 adults |

Varies by site |

Varied; ~50% male |

None |

|

Boccolini et al. [20] |

2016 |

Brazil |

Cross-sectional |

60,202 |

18+ |

47.1% male |

None |

|

Chen et al. [21] |

2022 |

China |

Commission Report |

Varied datasets used |

65+ for focus on older adults |

Not specified |

Longitudinal aspects from 1990s onward |

|

Dorjdagva et al. [22] |

2015 |

Mongolia |

Cross-sectional |

44,510 individuals (2007/2008), 47,908 individuals (2012) |

18+ |

Not specified |

None (cross-sectional) |

|

Ha et al. [23] |

2019 |

South Korea |

Cross-sectional |

2,003 workers |

Varied: Workers aged 15+ |

Varies; Male and Female Workers analyzed separately |

None (cross-sectional) |

|

Hoebel et al. [24] |

2017 |

Germany |

Cross-sectional |

11,811 participants |

64.3 |

5702:6109 |

None |

|

Hoven et al. [25] |

2023 |

Europe (Multiple Countries) |

Multilevel Poisson Regression Analysis |

31,616 respondents |

68 (Men), 67 (Women) |

14,429 Men : 17,187 Women |

Retrospective analysis with subsequent wave follow-up |

|

Jindal et al. [26] |

2020 |

India |

Cross-sectional, community-based |

10,330 individuals in 2066 households |

Above 14 years |

78.4% male (Household heads) |

None |

|

Liu et al. [27] |

2021 |

USA |

Cross-sectional survey |

108 participants |

22–31 years (55%) |

20% Black, 57% Hispanic |

None |

|

Mather et al. [28] |

2014 |

Australia |

Cross-sectional |

2,05,709 |

61.91 |

49.56% male |

Long-term cohort (45 and Up Study) |

|

Mziwira et al. [29] |

2022 |

Morocco |

Cross-sectional |

537 elderly individuals |

68.45 |

74.7% male |

None |

|

Njagi et al. [30] |

2020 |

Kenya |

Multilevel analysis of survey data |

33,675 households |

Varies (adults) |

Not specified |

None (cross-sectional) |

|

Petroze et al. [31] |

2014 |

Rwanda |

Cross-sectional, cluster-based |

3,175 individuals |

21.9 |

1:1.13 (Male : Female) |

None |

|

Rahman et al. [32] |

2024 |

Bangladesh |

Cross-sectional |

3,563 |

42.91 |

58% male |

None |

|

Saito et al. [33] |

2016 |

Nepal |

Cross-sectional household survey |

9,177 individuals in 1,997 households |

Not explicitly provided; categorized into <30, 30-59, 60+ |

1.01:1 (Male : Female) |

None |

|

Sangare et al. [34] |

2021 |

Mali |

Cross-sectional |

520 participants |

38 |

1.34 |

None |

|

Tran et al. [35] |

2016 |

Vietnam |

Cross-sectional |

200 respondents |

44.9 |

38% Male |

None |

|

Vahedi et al. [36] |

2021 |

Iran |

Cross-sectional |

13,005 respondents |

15+ |

Not specified |

None (cross-sectional) |

|

Wendt et al. [37] |

2022 |

Southern Brazil |

Cross-sectional |

1,300 |

46 |

Not provided |

None |

|

Zhuoga et al. [38] |

2023 |

Tibet, China |

Cross-sectional |

11,092 (2013) & 10,397 (2018) |

16+ years |

Balanced (Exact not provided) |

None |

Note: compiled by the authors.

Примечание: таблица составлена авторами.

Table 2. Socioeconomic factors and access-related information

Таблица 2. Социально-экономические факторы и информация о доступности медицинских услуг

|

Study ID |

Geographical Region |

Socioeconomic Determinants |

Type of Healthcare Service |

Access Barriers |

Access Facilitators |

Outcome Measures |

Policy Relevance |

Study Population Characteristics |

Methods of Assessment |

|

Andersson et al. [18] |

Europe |

Income, education |

Neurological care |

Low SES, limited neurologist access |

Public healthcare system |

Hospitalizations, income disparity |

SES-based epilepsy outcomes |

Adults with epilepsy |

Chi-square, logistic regression |

|

Bakibinga et al. [19] |

Africa, Asia |

Household budget, education |

Primary care |

Cost, poverty, location |

Universal Health Coverage (UHC) |

Healthcare expenditure, unmet needs |

Targeting slum-based inequities |

Slum residents |

Gini coefficients, regression |

|

Boccolini et al. [20] |

South America |

Income, education, social class |

General health screening |

Lack of private insurance, low income |

Unified Health System (SUS) |

Healthcare underutilization prevalence |

Reducing underutilization |

Adults aged 18+ in Brazil |

Multivariate logistic regression |

|

Chen et al. [21] |

East Asia |

Education, Income, Urban/Rural |

Primary, Long-term, Geriatric Care |

Health Literacy, Urban-Rural Divide |

Universal Health Insurance, LTCI |

Health Outcomes, NCD Burdens |

Ageing Policy, Health Systems |

Older Adults |

Qualitative and Quantitative |

|

Dorjdagva et al. [22] |

East Asia |

Income, Urban/Rural Divide |

Outpatient, Inpatient, Primary Care |

Financial Barriers, Regional Segmentation |

Social Health Insurance |

Horizontal Inequity, Utilization Rates |

Health Equity and Access |

Adults 18+ |

Erreygers Concentration Index |

|

Ha et al. [23] |

East Asia |

Employment Type, Income Level |

Hospital-based Services |

Precarious Employment, Long Hours |

Permanent Employment |

Unmet Healthcare Needs |

Labor Policy, Healthcare Access |

Workers (Permanent and Precarious) |

Multivariate Logistic Regression |

|

Hoebel et al. [24] |

Europe |

Education, occupation, income |

Medical, dental, mental |

Financial, geographic |

Insurance (Statutory and Private) |

Perceived unmet needs, health inequalities |

Improving health equity in aging populations |

Elderly population (50–85 years) |

Logistic regression, odds ratios |

|

Hoven et al. [25] |

Europe |

Employment history, occupational status |

General practitioners, specialists |

Cost, unavailability of services |

Universal healthcare access in Europe |

Barriers to healthcare based on employment |

European healthcare policy implications |

Retrospective data from adults (52–80 years) |

Multilevel regression analysis |

|

Jindal et al. [26] |

South Asia |

Income, education, housing type |

Surgical services |

Financial constraints, trust issues |

Free/subsidized healthcare |

Surgical met/unmet needs |

Address unmet surgical needs in urban slums |

Low-income slum population |

SOSAS, descriptive and bivariate analysis |

|

Liu et al. [27] |

North America |

Financial stress, poverty |

Prenatal care services |

Financial stress, social risks |

Clinic-based financial services |

Interest in financial services |

Integrating financial services |

Low-income prenatal patients |

Multivariate log-binomial regression |

|

Mather et al. [28] |

Oceania |

Income, education, SEIFA Index |

Medical and dental consultations |

SES-based disparities |

Universal healthcare |

Health inequality via RII |

SES-sensitive health policies |

Adults aged 45+ in Australia |

Relative Index of Inequality (RII) |

|

Mziwira et al. [29] |

North Africa |

Education, employment, marital status |

Primary healthcare |

Gender disparities in health access |

Government healthcare programs |

Chronic diseases, healthcare utilization |

Improve elderly healthcare policies |

Elderly population (60+) |

Structured interviews, anthropometric data |

|

Njagi et al. [30] |

Africa |

Wealth, education |

Inpatient, outpatient services |

Cost-related unmet need |

Health financing mechanisms |

Unmet healthcare needs due to cost |

Health equity in Kenya |

Kenyan households |

Multilevel logistic regression |

|

Petroze et al. [31] |

Sub-Saharan Africa |

Income, rural vs urban |

Surgical, primary, and secondary care |

Low surgical workforce density |

National health insurance |

Injury-related surgical needs, disabilities |

Strengthen surgical care in LMICs |

Mixed rural and urban |

SOSAS survey tool |

|

Rahman et al. [32] |

Asia |

Wealth quintile, occupation, region |

Government and private healthcare |

Cost, family support, facility absence |

Government hospitals, wealthier regions |

Healthcare access within 3 months |

Disability-inclusive health programs |

Persons with disabilities in Bangladesh |

Multilevel mixed-effect logistic regression |

|

Saito et al. [33] |

South Asia |

Household economic status, education level, marital status |

Public, private, and traditional healthcare providers |

Economic burden, underutilization of public services |

Free essential drug provision at public facilities |

Healthcare utilization across provider types, horizontal inequity index (HI) |

Strengthening public healthcare access for the poorest |

Urban households; demographic distribution of need factors (age, sex, morbidity) |

Concentration index, decomposition analysis, horizontal inequity index (HI) |

|

Sangare et al. [34] |

West Africa |

Poverty, gender, education |

Community-based health interventions |

Cost, transportation, gender |

Community health workers |

Barriers to health access, perception of healthcare |

Health policy for nomadic communities |

Nomadic communities |

Survey and chi-squared tests |

|

Tran et al. [35] |

Southeast Asia |

Ethnicity, income, household expenditure |

Modern and traditional medicine |

Distance, quality, cost |

Community health centers |

Health-related quality of life, HRQOL |

Healthcare improvement in rural Vietnam |

Residents in remote/mountainous areas |

Descriptive and multivariate regression |

|

Vahedi et al. [36] |

Middle East |

Education, Income, Residence Type |

Outpatient Services |

Cost, Service Availability |

Complementary Insurance |

Unmet Need Prevalence, Causes |

Healthcare System Equity |

General Population 15+ |

Multivariable logistic regression |

|

Wendt et al. [38] |

South America |

Income, assets index, education |

Medical and dental consultations |

Low public health coverage for poor |

Family Health Strategy |

Health service accessibility disparities |

Addressing local inequalities |

Urban adults aged 18+ in Southern Brazil |

Complex measures of inequality (SII, CIX) |

|

Zhuoga et al. [39] |

Asia |

Income, education, employment status |

Inpatient care |

Geographic and financial |

NRCMS, government reforms |

Inpatient care utilization and unmet needs |

Improving equity in Tibet |

Residents aged 16+ in Tibet |

Concentration and inequity indices |

Note: compiled by the authors.

Примечание: таблица составлена авторами.

Table 3. Barriers, healthcare system features, and cultural aspects

Таблица 3. Препятствия, особенности системы здравоохранения и культурные аспекты

|

Study ID |

Country Income Classification |

Barriers to Access |

Healthcare System Characteristics |

Provider Availability |

Cultural and Behavioral Factors |

Facilitators to Access |

Equity Considerations |

Long-Term Impact |

Statistical Measures Used |

|

Andersson et al. [18] |

High Income |

Low SES impacting access |

Universal healthcare system |

Neurology-specialized care |

Access linked to SES |

Public insurance |

Epilepsy severity linked to SES |

Improved epilepsy outcomes |

Regression analysis |

|

Bakibinga et al. [19] |

Low and Lower-Middle Income |

Inequities in household budgets |

Fragmented in slums |

Limited in slum areas |

Healthcare-seeking behavior differences |

Targeted interventions |

Within-slum disparities |

Improved UHC metrics |

Gini coefficients, regression models |

|

Boccolini et al. [20] |

Upper-Middle Income |

Low education and income levels |

Public-private gaps in SUS |

Concentrated in urban areas |

Health literacy gaps |

Family Health Strategy |

Race, income, and class factors |

Reduced inequities in Brazil |

Adjusted Odds Ratios (AOR) |

|

Chen et al. [21] |

Upper-Middle Income |

Urban-Rural Divide, Cultural Barriers |

Integrated, Aging Focus |

Geriatric, Rehabilitation Shortages |

Family Care Traditions |

Age-Friendly Environments |

Urban-Rural, Gender, Income |

LTCI Integration Challenges |

Prevalence, Mortality Trends |

|

Dorjdagva et al. [22] |

Lower-Middle Income |

Financial Costs, Geographic Access |

Fragmented, Regionally Segmented |

Shortages in Rural Areas |

Stigma, Health-Seeking Behavior |

Government Strategies, Insurance |

Pro-Rich and Pro-Poor Inequity |

Policy Reform Needs |

Concentration Indices |

|

Ha et al. [23] |

High Income |

Precarious Jobs, Low Income |

Universal but Variable |

Varies by Employment Type |

Long Work Hours |

Permanent Worker Benefits |

Employment-based Inequities |

Workplace Health Policy |

Odds Ratios, Logistic Models |

|

Hoebel et al. [24] |

High Income |

Financial and social inequities |

Integrated with statutory/private insurance |

Available but urban-focused |

Health literacy, self-perceived needs |

Insurance systems |

Age, income, region |

Potential policy reform for aging |

Odds ratios, prevalence rates |

|

Hoven et al. [25] |

High Income |

Cost, employment adversities |

Universal but inequities persist |

Varies by country and region |

Employment-related access disparity |

Universal health coverage (UHC) |

Employment history and gender disparities |

Better integration of social and health policies |

Multilevel Poisson regression |

|

Jindal et al. [26] |

Lower-Middle Income |

Cost, lack of awareness, trust |

Universal free/subsidized care |

Surgical workforce shortages |

Mistrust in system, fear of surgery |

Community engagement, free programs |

Targeting marginalized groups |

Reduced unmet surgical needs |

Descriptive and bivariate analysis |

|

Liu et al. [27] |

High Income |

Financial stress, poverty |

Safety-net system |

Clinic-specific providers |

Stigma of poverty |

Integrated services in clinics |

SES-based health disparities |

Mitigation of poverty impact |

Adjusted Risk Ratios |

|

Mather et al. [28] |

High Income |

Area-based SES underestimates inequality |

Universal healthcare |

Ample |

Weaker SES-health link in elderly |

SES-independent policies |

Young vs elderly SES disparities |

SES-specific health policies |

RII across SES measures |

|

Mziwira et al. [29] |

Lower-Middle Income |

Gender-based disparities |

Government-supported |

Limited access in rural areas |

Traditional norms, gender roles |

Healthcare system reforms |

Gender-sensitive policies |

Enhanced elderly healthcare services |

Chi-square, Tukey's test |

|

Njagi et al. [30] |

Lower-Middle Income |

Cost-related barriers |

Devolved county systems |

Uneven across counties |

Perceptions of illness seriousness |

County-based health initiatives |

County variations |

Reduced regional disparities |

ICC, multilevel models |

|

Petroze et al. [31] |

Low Income |

Geographic, workforce, financial |

Decentralized, insurance-based |

Limited surgeons and infrastructure |

Stigma, limited health literacy |

National health insurance coverage |

Address rural disparities |

Improved injury-related care |

Population-weighted descriptive stats |

|

Rahman et al. [32] |

Lower-Middle Income |

Costs, lack of family support |

Government-driven, merit-based care |

Overcrowded and limited disability-friendly |

Disability stigma in LMICs |

Regional health programs |

Wealth quintiles |

Better disability health coverage |

Multilevel regression |

|

Saito et al. [33] |

Low Income |

Pro-rich bias in private healthcare utilization, limited public utilization despite free services |

Public sector financed through general government revenues; private sector operates on fee-for-service basis |

Limited public service uptake; higher utilization of private providers |

Stigma, limited awareness of free public services |

Free essential medicines at public facilities |

Addressing economic disparities in utilization |

Potential for reducing household financial burdens through better public health management |

Concentration index (CI: 0.062 for all providers, 0.070 for private), Horizontal Inequity Index (HI: 0.029 for all providers) |

|

Sangare et al. [34] |

Low Income |

Cost, transportation, cultural norms |

Poorly distributed facilities |

Sparse availability |

Gender preferences, lifestyle barriers |

Community healthcare workers |

Poverty and education gaps |

Targeted nomadic healthcare policies |

Descriptive stats, chi-squared tests |

|

Tran et al. [35] |

Lower Middle Income |

Cost, distance, poor service quality |

Community-based health centers, TM |

Community health providers |

Traditional vs modern medicine beliefs |

Local health centers |

Ethnicity, rural vs urban disparities |

Improved rural health outcomes |

HRQOL scores, multivariate regression |

|

Vahedi et al. [36] |

Upper-Middle Income |

Cost, Accessibility, Acceptability |

Under-resourced in Areas |

Varies by Region |

Postponement, Self-Medication |

Supplementary Insurance |

Economic and Regional Disparities |

Healthcare Reform |

Odds Ratios, Logistic Models |

|

Wendt et al. [38] |

Upper-Middle Income |

Healthcare disparity by wealth and SES |

Low local health services availability |

Variable in urban zones |

Diverse urban-rural behaviors |

Family Health Program |

Quartile-based wealth measures |

Targeted public health strategies |

Slope Index (SII), Concentration Index (CIX) |

|

Zhuoga et al. [39] |

Upper-Middle Income |

High-altitude logistics, financial hardship |

NRCMS with low professional density |

Sparse in rural regions |

Traditional beliefs, chronic disease focus |

Health reforms improving affordability |

Gender and region-sensitive needs |

Improved equity indices |

HI, concentration indices |

Note: compiled by the authors.

Примечание: таблица составлена авторами.

Table 4. Policy details, challenges, and global comparisons

Таблица 4. Детали проводимой политики, проблемы и сравнения на глобальном уровне

|

Study ID |

Policy Type |

Policy Level |

Target Population |

Implementation |

Cost-Effectiveness |

Success Indicators |

Equity Impact |

Case Examples |

Global Comparisons |

|

Andersson et al. [18] |

SES-based interventions |

National (Sweden) |

Low SES adults with epilepsy |

Ensuring equitable access |

Not assessed |

Improved care access for epilepsy |

SES-aligned care improvements |

SES-focused epilepsy care reforms |

SES and epilepsy in public systems |

|

Bakibinga et al. [19] |

Health equity-focused reforms |

Community and national |

Slum residents |

Identifying the poorest households |

Not explicitly evaluated |

Reduced healthcare inequality |

Addressing slum inequities |

CHE measurement approaches |

UHC challenges in LMICs |

|

Boccolini et al. [20] |

Universal health access |

National |

Poor and vulnerable Brazilians |

Persistent inequalities |

Not explicitly evaluated |

Higher access among poor |

Pro-poor access improvements |

Family Health Strategy outcomes |

Global SUS comparisons |

|

Chen et al. [21] |

Ageing, Healthcare Integration |

National and Regional |

Older Adults |

Fragmentation, Funding Gaps |

Qualitative Evidence |

Improved Health Outcomes |

Gender and Regional Equity |

LTCI Pilots in Cities |

HIC and LMIC Policies |

|

Dorjdagva et al. [22] |

Health Financing, Access |

National |

General Population |

Rural Accessibility, Financing Gaps |

Limited Data |

Reduction in Inequity |

Pro-Poor Outcomes |

Social Health Insurance Implementation |

Developing Countries |

|

Ha et al. [23] |

Worker Protection, Health Policy |

National |

Workers (Permanent, Precarious) |

Enforcement of Worker Benefits |

Not Evaluated |

Reduction in Unmet Needs |

Improved Worker Health Access |

None Provided |

OECD Nations |

|

Hoebel et al. [24] |

Health equity and access |

National |

Elderly |

Statutory vs private insurance inequities |

Not evaluated |

Reduced inequities in aging |

Age, region, income disparities |

Insurance reforms |

European aging policies |

|

Hoven et al. [25] |

Workplace and healthcare integration |

European (Multiple Countries) |

Adults with employment history |

Persistent historical adversities |

Not evaluated |

Reduced perceived barriers |

Work-related health disparities |

European comparisons |

Global healthcare access studies |

|

Jindal et al. [26] |

Urban healthcare interventions |

Local (Urban slums) |

Low-income urban population |

Awareness, infrastructure gaps |

Not evaluated |

Higher surgical utilization rates |

Reducing slum healthcare disparities |

Universal health programs in India |

Urban slum health globally |

|

Liu et al. [27] |

Financial service integration |

Local (Clinic-based) |

Low-income prenatal patients |

Coordination of financial services |

Not assessed |

Interest in financial services |

Reducing financial barriers |

Clinic-based financial services |

Clinic-based services in poverty |

|

Mather et al. [28] |

SES-based health reforms |

National |

Elderly Australians |

Sensitive SES measurements |

Not explicitly evaluated |

Reduced SES-based health disparity |

Improved SES-sensitive health outcomes |

RII evaluations |

Oceania SES studies |

|

Mziwira et al. [29] |

Elderly health policy |

National |

Elderly individuals |

Gender disparities, resource allocation |

Not evaluated |

Improved healthcare access |

Gender equity in healthcare |

Elderly care reforms in Morocco |

Elderly healthcare in North Africa |

|

Njagi et al. [30] |

County-level health financing |

County and national |

Marginalized Kenyan households |

Cost burden |

Not evaluated |

Reduced cost-related unmet need |

Regional equity in access |

County-based initiatives |

Kenyan health disparities |

|

Petroze et al. [31] |

Surgical care policy |

National |

General population, injured individuals |

Workforce and resource constraints |

Not evaluated |

Reduced injury-related unmet needs |

Geographic and income parity |

SOSAS application in Rwanda |

Surgical disparities in LMICs |

|

Rahman et al. [32] |

Disability-inclusive policies |

National |

Persons with disabilities in Bangladesh |

Disability stigma and infrastructure |

Not explicitly evaluated |

Better healthcare service access |

Disability-aware access reforms |

Regional healthcare models |

Disability studies in LMICs |

|

Saito et al. [33] |

Health equity and financial protection policies |

National |

Urban households in low-income settings |

High out-of-pocket payments, inadequate financial protection coverage |

Not evaluated |

Reduced inequities in healthcare utilization, increased use of public services |

Pro-poor utilization trends in public services |

Free essential drug provision as a starting point |

Comparison with public-private equity in Hong Kong, Bangladesh, and African nations |

|

Sangare et al. [34] |

Community-based intervention |

Regional |

Nomadic communities |

Mobility and poverty |

Not evaluated |

Increased access for nomads |

Access for marginalized groups |

Cultural-sensitive interventions |

Nomadic health globally |

|

Tran et al. [35] |

Rural health enhancement |

National |

Rural residents |

Distance and traditional medicine reliance |

Not evaluated |

Improved HRQOL |

Rural vs urban equity |

Community health initiatives |

Rural health challenges in LMICs |

|

Vahedi et al. [36] |

Healthcare Equity |

National |

General Population |

Financial Sustainability |

Not Evaluated |

Decreased SUN Rates |

Regional and Economic Equity |

None Provided |

Regional Studies in MENA |

|

Wendt et al. [38] |

Targeted equity programs |

Local |

Urban poor in Southern Brazil |

Healthcare access gaps |

Not explicitly evaluated |

Improved local health equity |

Wealth-based access parity |

FHS implementation results |

Local vs national health disparities |

|

Zhuoga et al. [39] |

Equity-focused healthcare |

National |

High-need residents in Tibet |

Geographic barriers |

Not explicitly evaluated |

Reduced unmet healthcare needs |

Income and region-sensitive equity |

NRCMS contributions |

Chinese equity in LMICs |

Note: compiled by the authors.

Примечание: таблица составлена авторами.

Fig. 2. Bias assessment across the cross-sectional studies included in the review

Notes: The figure was created by the authors; D1 — Selectioon; D2 — Performance; D3 — Detection; D4 — Attrition; D5 — Reporting; D6 — Other.

Рис. 2. Оценка систематической ошибки в поперечных исследованиях, включенных в обзор

Примечания: рисунок выполнен авторами; D1 — отбор; D2 — проведение; D3 — выявление; D4 — отсев; D5 — выборочное сообщение; D6 — другое.

Fig. 3. Bias assessment across the cohort studies and reports included in the review

Notes: The figure was created by the authors. Domains: D1 — Bias due to confounding; D2 — Bias due to selection of participants; D3 — Bias in classification of interventions; D4 — Bias due to deviations from intended interventions. D5 — Bias due to missing data; D6 — Bias in measurement of outcomes; D7 — Bias in selection of the reported result.

Рис. 3. Оценка систематической ошибки в когортных исследованиях и отчетах, включенных в обзор

Примечания: рисунок выполнен авторами; Домены: D1 — риск влияния вмешивающихся факторов; D2 — предвзятость при отборе участников; D3 — предвзятость при классификации вмешательств; D4 — смещение, связанное с отклонением от намеченного вмешательства; D5 — смещение, связанное с отсутствием данных; D6 — предвзятость в оценке результатов; D7 — выборочное представление результатов.

DISCUSSION

Impact of Healthcare Policies on Addressing Health Disparities

Healthcare policies tend to play a critical role in defining strategies and outcomes when addressing health disparities. Policies at all levels-national, regional, and institutional-impacted access to and quality of health care services. Such factors as funding mechanisms, insurance frameworks, reimbursement policies, and models of healthcare delivery determine the manner in which resources are equitably distributed and utilized. Thus, a complete understanding of the dynamics of these aspects should be sought by health managers in order to design and implement interventions that have the appropriate impact [39].

However, a few policies might indirectly worsen disparities through the resultant imbalance in the distribution of resources. An example is funding mechanisms that may not take into account the needs of underserved populations or marginalized communities. Such mechanisms, therefore, will perpetuate existing disparities [40]. Balancing these imbalances calls upon healthcare managers to advocate for inclusive funding models that specifically target vulnerable communities. In that regard, cultural competence will be integrated into policy frameworks such that healthcare services are responsive to diverse population needs [41]. This includes policies which require cultural competency training, support for interpreter services and culturally tailored care, all of which enables healthcare managers to provide more responsive and inclusive care.

Demographic trends, such as aging populations, require policy changes responsive to their distinct health-care needs. Policies that can support targeted approaches for the elderly may be able to empower healthcare managers to place resources effectively in designing services meeting those particular needs [42]. Policies that focus on patient-centered care can also greatly decrease disparities. This kind of care approach focuses on involving the patient in decision-making and incorporates social determinants of health into care. This provides health managers with a structured approach to address inequities [43]. The advancement of health information technology, including electronic health records and telehealth, offers opportunities to enhance access, communication, and outcome monitoring [44]. Making policies to adopt these technologies is essential to support healthcare managers in minimizing disparities across diverse populations [45].

Thematic Assessments Obtained in this Review

Studies conducted in high-income areas, such as those of Andersson et al. [18], Hoebel et al. [24], and Hoven et al. [25], continue to find SES and work-related differences are major contributors to problems related to the accessibility of care, regardless of having a universal care system in place. These findings were similar in their focus on SES-sensitive inequities but differed in their emphasis; for example, Andersson et al. [18] linked low SES with specialized neurological care gaps, whereas Hoebel et al. [24] emphasized disparities in health literacy among elderly populations. Hoven et al. [25] added a broader European perspective, highlighting regional and employment-based inequities.

In middle-income countries like Brazil (Boccolini et al. [20]) and China (Chen et al. [21]), urban-rural divides and gaps in public-private healthcare integration were salient themes. They converged on financial barriers and systemic inefficiencies as challenges but diverged in scope. Boccolini et al. [20] focused on underutilization through the Family Health Strategy, whereas Chen et al. [21] looked at long-term care needs and aging-focused health reforms. Both studies showed the relevance of integrated health policies but presented different challenges for specific populations. Low-income contexts from Mali (Sangare et al. [34]) and Kenya (Njagi et al. [30]) reported high geographical and cost-related barriers, consistent with a lack of infrastructure and insufficient workforce. Sangare et al. [34] pointed to cultural barriers as including gender roles, but Njagi et al. [30] referenced regional inequalities that are enhanced through cost-related barriers. Results were similar in indicating multiple layers of poverty, though they differed in focusing more on cultural or systemic aspects.

Community-based interventions studies, such as Petroze et al. [31] in Rwanda and Tran et al. [35] in Vietnam, emphasize the same kind of success into healthcare access among the rural and deprived populations. Both the studies emphasized the importance of the local health center and community involvement, though Petroze et al. [31] emphasized surgical care gaps, whereas Tran et al. [35] stated to integrate traditional and modern medicines. Methodologically, studies such as Dorjdagva et al. [22] and Saito et al. [33] of Asia applied more advanced measurements like concentration indices to the measurement of inequity. These statistical approaches made it possible to have relatively comparable insights into pro-rich trends in utilization, with analyses of similar rigor. However, the context of inequities—financial costs in Mongolia [22] versus provider shortages in Nepal [33]—emphasized contextual variability.

Misinformation and Health Care Decisions

Our review findings indicated that structural barriers include socioeconomic disparities, and Reyna et al. [47] pointed out cognitive processing and misinformation in healthcare decision-making. Reyna et al. [47] determined how misinformation shapes perceptions of health care, and "gist" processing influences decisions more strongly than factual knowledge. This dimension was absent in our review; however, it emphasizes that public health strategies must address misinformation in order to improve the uptake of preventive care services.

Economic Crises and Health Inequities

Our review identified financial resource constraints as an important obstacle for access to healthcare, particularly for low- and middle-income settings. Broadbent et al. [48] extended this by examining the wider ripple effects of economic crises; for example, cost-of-living crisis, on population health, pointing out how policy intervention, such as welfare provision, can help mitigate vulnerable populations. While our review looked specifically at direct financial barriers from the healthcare system, Broadbent et al. [48] took a broader macroeconomic view, highlighting the role of integrated policies in tackling health inequities.

Equity in Public Health Practice

Both our review and Liburd et al. [49] highlighted the role of health equity in public health practice. Liburd et al. [48] noted the need for multifaceted frameworks and culturally competent interventions in achieving equity, similar to the specific recommendations in our review about tailoring interventions to underserved groups. In contrast, Liburd et al. [49] emphasized the conceptual approach to integrate equity into public health functions and added more to the idea of the integration of equity in public health functions.

Population-Specific Challenges

Our review discussed barriers and facilitators to health care access among different population groups, whereas Mytton et al. [50] have emphasized the significance of adolescence as a critical period in the life cycle. They underscored long-term consequences of health behaviors and rising risks during adolescence, including vaping and online harms. Although our results were more general, addressing population-level inequities, Mytton et al. [50] provided some insight into how to address vulnerabilities in a particular population, emphasizing the importance of age-sensitive policy interventions.

Healthcare Quality and Safety

Vikan et al. [51] assessed the linkage of patient safety culture score to the rate of adverse events as part of highlighting the safety considerations in service delivery. Though our literature review is centered around inequities and equity in the delivery of health care, Vikan et al. [51] was keen on quality aspects in healthcare services. The general consensus, as observed by the review, suggested the requirement for consistent approaches and more elaborate analysis of assessments toward healthcare in the entire sector.

Implementation of Universal Health Coverage

Our review and Preker et al. [52] both highlighted the potential of UHC to reduce inequities. Preker et al. [51] specifically looked at the implementation of UHC in middle- and upper-middle-income countries, focusing on challenges related to political sustainability and resource constraints. While our review looked at access barriers and facilitators, Preker et al. [52] provided a detailed analysis of institutional factors that affect UHC sustainability, thus providing a complementary perspective on how to achieve equitable healthcare systems.

Limitations

This study was limited by the heterogeneity in study designs, populations, and methodologies that limited the possibility of comparisons between findings. The inclusion of cross-sectional studies prevented inferring causality. Differences in socioeconomic and healthcare system characteristics across regions introduced contextual biases, and the generalizability of results was compromised. In addition, the lack of standardized metrics for evaluating healthcare access and equity led to inconsistencies in reported outcomes. Numerous studies suffered from missing longitudinal follow-up, which made it not possible to evaluate properly long-term impacts of policies. Many studies were based on self-reported information, which increased recall and reporting bias, and some regions were underrepresented in rural and marginalized populations, limiting the generalizability of results.

Future Implications and Recommendations

Access to care could be made fairer through financial and geographical barriers reduction, especially in low- and middle-income regions. Reducing disparities will require integrated healthcare systems with a balance of urban and rural focuses. Community-based interventions should be a part of Universal Health Coverage initiatives, and there must be a strengthening of health infrastructure in underserved regions. Health literacy improvement and stigma reduction should be especially emphasized among vulnerable populations. Consistent measures to evaluate access to and equity in healthcare need to be developed to maintain standards in research and policy review. Additionally, longitudinal studies should be encouraged to better understand the long-term impact of health policies.

CONCLUSION

The obtained findings collectively demonstrate that healthcare access is universally influenced by SES, financial, and geographic barriers, albeit with regional variations. High-income studies provided insights into nuanced inequities within robust systems, while middle- and low-income studies highlighted structural and resource-related challenges. Despite differences in focus, the findings consistently underscored the need for equity-sensitive, context-specific health policies to mitigate disparities globally. Such comparisons highlighted large thematic consistencies while demonstrating the vast regional challenges that shape healthcare access.

References

1. Ni X, Li Z, Li X, Zhang X, Bai G, Liu Y, Zheng R, Zhang Y, Xu X, Liu Y, Jia C, Wang H, Ma X, Zheng H, Su Y, Ge M, Zeng Q, Wang S, Zhao J, Zeng Y, Feng G, Xi Y, Deng Z, Guo Y, Yang Z, Zhang J. Socioeconomic inequalities in cancer incidence and access to health services among children and adolescents in China: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2022;400(10357):1020–1032. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01541-0

2. Ahonen EQ, Winkler MR, Hajat A. Work, Health, and the Ongoing Pursuit of Health Equity. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(21):14047. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192114047

3. Mafla AC, Moran LS, Bernabe E. Maternal Oral Health and Early Childhood Caries amongst Low-Income Families. Community Dent Health. 2020;37(3):223–228. https://doi.org/10.1922/CDH_00040Mafla06

4. Brown LE, França UL, McManus ML. Socioeconomic Disadvantage and Distance to Pediatric Critical Care. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2021;22(12):1033–1041. https://doi.org/10.1097/PCC.0000000000002807

5. Zhou Y, Guo Y, Liu Y. Health, income and poverty: evidence from China's rural household survey. Int J Equity Health. 2020;19(1):36. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-020-1121-0

6. D'Avila OP, Chisini LA, Costa FDS, Cademartori MG, Cleff LB, Castilhos ED. Use of Health Services and Family Health Strategy Households Population Coverage in Brazil. Cien Saude Colet. 2021;26(9):3955– 3964. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232021269.11782021

7. Hong SN, Kim JK, Kim DW. The Impact of Socioeconomic Status on Hospital Accessibility in Otorhinolaryngological Disease in Korea. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2021;33(2–3):287–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1010539520977320

8. Montañez-Hernández JC, Alcalde-Rabanal J, Reyes-Morales H. Socioeconomic factors and inequality in the distribution of physicians and nurses in Mexico. Rev Saude Publica. 2020;54:58. https://doi.org/10.11606/s1518-8787.2020054002011

9. Asare AO, Maurer D, Wong AMF, Ungar WJ, Saunders N. Socioeconomic Status and Vision Care Services in Ontario, Canada: A Population-Based Cohort Study. J Pediatr. 2022;241:212–220.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2021.10.020

10. Dantas MNP, Souza DLB, Souza AMG, Aiquoc KM, Souza TA, Barbosa IR. Factors associated with poor access to health services in Brazil. Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2020;24:e210004. Portuguese, English. https://doi.org/10.1590/1980-549720210004

11. Cheng JM, Batten GP, Cornwell T, Yao N. A qualitative study of healthcare experiences and challenges faced by ageing homebound adults. Health Expect. 2020;23(4):934–942. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13072

12. Meshesha BR, Sibhatu MK, Beshir HM, Zewude WC, Taye DB, Getachew EM, Merga KH, Kumssa TH, Alemayue EA, Ashuro AA, Shagre MB, Gebreegziabher SB. Access to surgical care in Ethiopia: a cross-sectional retrospective data review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022;22(1):973. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08357-9

13. Olfson M, Mauro C, Wall MM, Choi CJ, Barry CL, Mojtabai R. Healthcare coverage and service access for low-income adults with substance use disorders. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;137:108710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108710

14. Aronu NI, Atama CS, Chukwu NE, Ijeoma I. Socioeconomic Dynamics in Women's Access and Utilization of Health Technologies in Rural Nigeria. Community Health Equity Res Policy. 2022;42(2):225–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272684X20972643

15. Page MJ, Moher D, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, McKenzie JE. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n160. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n160

16. Igelström E, Campbell M, Craig P, Katikireddi SV. Cochrane's risk of bias tool for non-randomized studies (ROBINS-I) is frequently misapplied: A methodological systematic review. J Clin Epidemiol. 2021 Dec;140:22–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.08.022

17. Downes MJ, Brennan ML, Williams HC, Dean RS. Development of a critical appraisal tool to assess the quality of cross-sectional studies (AXIS). BMJ Open. 2016;6(12):e011458. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011458

18. Andersson K, Ozanne A, Edelvik Tranberg A, E Chaplin J, Bolin K, Malmgren K, Zelano J. Socioeconomic outcome and access to care in adults with epilepsy in Sweden: A nationwide cohort study. Seizure. 2020;74:71–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seizure.2019.12.001

19. Improving Health in Slums Collaborative. Inequity of healthcare access and use and catastrophic health spending in slum communities: a retrospective, cross-sectional survey in four countries. BMJ Glob Health. 2021;6(11):e007265. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007265

20. Boccolini CS, de Souza Junior PR. Inequities in Healthcare utilization: results of the Brazilian National Health Survey, 2013. Int J Equity Health. 2016;15(1):150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-016-0444-3

21. Chen X, Giles J, Yao Y, Yip W, Meng Q, Berkman L, Chen H, Chen X, Feng J, Feng Z, Glinskaya E, Gong J, Hu P, Kan H, Lei X, Liu X, Steptoe A, Wang G, Wang H, Wang H, Wang X, Wang Y, Yang L, Zhang L, Zhang Q, Wu J, Wu Z, Strauss J, Smith J, Zhao Y. The path to healthy ageing in China: a Peking University-Lancet Commission. Lancet. 2022;400(10367):1967–2006. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01546-X

22. Dorjdagva J, Batbaatar E, Dorjsuren B, Kauhanen J. Income-related inequalities in health care utilization in Mongolia, 2007/2008-2012. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-015-0185-8

23. Ha R, Jung-Choi K, Kim CY. Employment Status and Self-Reported Unmet Healthcare Needs among South Korean Employees. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2018;16(1):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph16010009

24. Hoebel J, Rommel A, Schröder SL, Fuchs J, Nowossadeck E, Lampert T. Socioeconomic Inequalities in Health and Perceived Unmet Needs for Healthcare among the Elderly in Germany. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(10):1127. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14101127

25. Hoven H, Backhaus I, Gerő K, Kawachi I. Characteristics of employment history and self-perceived barriers to healthcare access. Eur J Public Health. 2023;33(6):1080–1087. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckad178

26. Jindal RM, Tiwari S. Challenges to Achieving Surgical Equity in Slums. Int J Public Health. 2025 Jan 13;69:1608098. https://doi.org/10.3389/ijph.2024.1608098

27. Liu PY, Bell O, Wu O, Holguin M, Lozano C, Jasper E, Saleeby E, Smith L, Szilagyi P, Schickedanz A. Interest in Clinic-Based Financial Services among Low-Income Prenatal Patients and its Association with Health-Related Social Risk Factors. J Prim Care Community Health. 2021;12:21501327211024425. https://doi.org/10.1177/21501327211024425

28. Mather T, Banks E, Joshy G, Bauman A, Phongsavan P, Korda RJ. Variation in health inequalities according to measures of socioeconomic status and age. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2014;38(5):436–440. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12239

29. Mziwira M, Ahaji A, Naciri K, Belahsen R. Socio-economic characteristics, health status and access to health care in an elderly Moroccan community: study of the gender factor. Rocz Panstw Zakl Hig. 2022;73(3):341–349. https://doi.org/10.32394/rpzh.2022.0224

30. Njagi P, Arsenijevic J, Groot W. Cost-related unmet need for healthcare services in Kenya. BMC Health Serv Res. 2020;20(1):322. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-05189-3

31. Petroze RT, Joharifard S, Groen RS, Niyonkuru F, Ntaganda E, Kushner AL, Guterbock TM, Kyamanywa P, Calland JF. Injury, disability and access to care in Rwanda: results of a nationwide cross-sectional population study. World J Surg. 2015;39(1):62–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-014-2544-9

32. Rahman M, Rana MS, Rahman MM, Khan MN. Healthcare services access challenges and determinants among persons with disabilities in Bangladesh. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):19187. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-70418-2

33. Saito E, Gilmour S, Yoneoka D, Gautam GS, Rahman MM, Shrestha PK, Shibuya K. Inequality and inequity in healthcare utilization in urban Nepal: a cross-sectional observational study. Health Policy Plan. 2016;31(7):817–824. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czv137

34. Sangare M, Coulibaly YI, Coulibaly SY, Dolo H, Diabate AF, Atsou KM, Souleymane AA, Rissa YA, Moussa DW, Abdallah FW, Dembele M, Traore M, Diarra T, Brieger WR, Traore SF, Doumbia S, Diop S. Factors hindering health care delivery in nomadic communities: a cross-sectional study in Timbuktu, Mali. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):421. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10481-w

35. Tran BX, Nguyen LH, Nong VM, Nguyen CT. Health status and health service utilization in remote and mountainous areas in Vietnam. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2016;14:85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12955-016- 0485-8

36. Vahedi S, Torabipour A, Takian A, Mohammadpur S, Olyaeemanesh A, Kiani MM, Mohamadi E. Socioeconomic determinants of unmet need for outpatient healthcare services in Iran: a national cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21(1):457. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-10477-6

37. Vora K, Saiyed S, Shah AR, Mavalankar D, Jindal RM. Surgical Unmet Need in a Low-Income Area of a Metropolitan City in India: A Cross-Sectional Study. World J Surg. 2020;44(8):2511–2517. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00268-020-05502-5

38. Wendt A, Marmitt LP, Nunes BP, Dumith SC, Crochemore-Silva I. Socioeconomic inequalities in the access to health services: a population-based study in Southern Brazil. Cien Saude Colet. 2022;27(2):793– 802. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232022272.03052021

39. Zhuoga C, Cuomu Z, Li S, Dou L, Li C, Dawa Z. Income-related equity in inpatient care utilization and unmet needs between 2013 and 2018 in Tibet, China. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22(1):85. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-023-01889-4

40. Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ. Global epidemiology of migraine and its implications for public health and health policy. Nat Rev Neurol. 2023;19(2):109–117. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41582-022-00763-1

41. Lim Z, Sebastin SJ, Chung KC. Health Policy Implications of Digital Replantation. Clin Plast Surg. 2024;51(4):553–558. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2024.02.017

42. Manji K, Perera S, Hanefeld J, Vearey J, Olivier J, Gilson L, Walls H. An analysis of migration and implications for health in government policy of South Africa. Int J Equity Health. 2023;22(1):82. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-023-01862-1

43. Townsend JR, Kirby TO, Marshall TM, Church DD, Jajtner AR, Esposito R. Foundational Nutrition: Implications for Human Health. Nutrients. 2023;15(13):2837. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu15132837

44. Wong BLH, Maaß L, Vodden A, van Kessel R, Sorbello S, Buttigieg S, Odone A; European Public Health Association (EUPHA) Digital Health Section. The dawn of digital public health in Europe: Implications for public health policy and practice. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2022;14:100316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2022.100316

45. Li C, Zhu B, Zhang J, Guan P, Zhang G, Yu H, Yang X, Liu L. Epidemiology, health policy and public health implications of visual impairment and age-related eye diseases in mainland China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:966006. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.966006

46. Franco-Rocha OY, Carillo-Gonzalez GM, Garcia A, Henneghan A. Cancer Survivorship Care in Colombia: Review and Implications for Health Policy. Hisp Health Care Int. 2022;20(1):66–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/15404153211001578

47. Reyna VF. A scientific theory of gist communication and misinformation resistance, with implications for health, education, and policy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2021;118(15):e1912441117. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1912441117

48. Broadbent P, Thomson R, Kopasker D, McCartney G, Meier P, Richiardi M, McKee M, Katikireddi SV. The public health implications of the cost-of-living crisis: outlining mechanisms and modelling consequences. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2023;27:100585. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanepe.2023.100585

49. Liburd LC, Hall JE, Mpofu JJ, Williams SM, Bouye K, Penman-Aguilar A. Addressing Health Equity in Public Health Practice: Frame- works, Promising Strategies, and Measurement Considerations. Annu Rev Public Health. 2020;41:417–432. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094119

50. Mytton OT, Donaldson L, Goddings AL, Mathews G, Ward JL, Greaves F, Viner RM. Changing patterns of health risk in adolescence: implications for health policy. Lancet Public Health. 2024;9(8):e629–e634. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(24)00125-7

51. Vikan M, Haugen AS, Bjørnnes AK, Valeberg BT, Deilkås ECT, Danielsen SO. The association between patient safety culture and adverse events — a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res. 2023;23(1):300. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-023-09332-8

52. Preker AS, Cotlear D, Kwon S, Atun R, Avila C. Universal health care in middle-income countries: Lessons from four countries. J Glob Health. 2021;11:16004. https://doi.org/10.7189/jogh.11.16004

About the Authors

Chintu ChaudharyIndia

Dr Chintu Choudhary - Professor, Department of Community Medicine,

N.H.-9, Delhi Road, Moradabad, 244001, Uttar Pradesh

Vinod K. Singh

India

Dr Vinod Kumar Singh - Professor, Department of Medicine,

N.H.-9, Delhi Road, Moradabad, 244001, Uttar Pradesh

Sadhna Singh

India

Dr Sadhna Singh - Professor, Department of Community Medicine,

N.H.-9, Delhi Road, Moradabad, 244001, Uttar Pradesh

Supplementary files

Review

For citations:

Chaudhary Ch., Singh V., Singh S. Socioeconomic determinants of access to preventive healthcare services challenges and policy implications: A systematic review. Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2025;32(4):96-114. https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2025-32-4-96-114