Scroll to:

Characterization of Pathogenic Microflora Causing Suppurative Septic Postpartum Complications: a Retrospective Cohort Study

https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2023-30-3-15-24

Abstract

Background. Suppurative septic postpartum complications occupy a leading position in the structure of causes of maternal mortality. Information about the characteristics of pathogenic microflora in various forms of complications and analysis of its resistance to antibacterial drugs determine the choice of rational therapy for this pathology.

Objectives — to characterize the isolated pathogenic microflora in obstetric patients with suppurative septic postpartum complications.

Methods. A retrospective cohort study was conducted at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2 of the Omsk State Medical University and the Department of Gynecology of the Omsk Regional Clinical Hospital. The study included 123 cesarean section patients treated from January 2013 to December 2022 who were divided into three groups: Group A — uncomplicated course of postpartum endometritis, n = 55; Group B — complicated forms of postpartum endometritis, n = 48: B1 — local complications (suture failure following cesarean section; parametritis) n = 29; B2 — pelvic peritonitis, n = 19; Group C — septic complications following critical obstetric conditions, n = 20. The pathogenic microflora of uterine and abdominal cavities was examined; the extent of contamination with a pathogen and sensitivity to antibacterial drugs were determined. The isolated microorganisms were identified using a MicroTax bacteriological analyzer (Austria), Vitek2 Compact (France) and routine methods; a disk diffusion method was employed to determine the sensitivity of microorganisms to antibacterial drugs. Calculations were performed using licensed Microsoft Office Excel 2013 and Statistica 10 programs (StatSoft Inc., USA). Nonparametric nominal data were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared test with p-value determination.

Results. The pathogenic microflora was dominated by S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, and E. faecium. In 2018–2022, a statistically significant decrease was observed in the isolation rate of S. epidermidis (p = 0.016), E. faecalis (p < 0.001), and E. faecium (p = 0.05). The highest resistance was exhibited by bacteria to the following antibiotics: S. epidermidis — cephalosporins (30.16%); E. faecalis — fluoroquinolones (33.33%); E. coli — cephalosporins (65.91%) and β-lactamase-resistant penicillins (40.91%); E. faecium — aminopenicillins (64.10%) and fluoroquinolones (50.0%); А. baumannii — fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, carbapenems (100%), and aminoglycosides (84.2%). A contamination assessment revealed a high titer of isolated microorganisms in 60.53% of cases. We found a statistically significantly higher isolation rate of S. еpidermidis (p < 0.001), E. faecium (p = 0.01), and A. baumannii (p = 0.02) in the setting of pelvic peritonitis as compared to uncomplicated endometritis. In the case of suppurative septic complications due to critical obstetric conditions, the isolation rate was higher for S. еpidermidis (p <0.001), E. coli (p = 0.04), E. faecium (p = 0.005), A. baumannii (р<0.001), and K. рneumoniae (p = 0.04).

Conclusion. The antibiotic resistance of pathogenic microorganisms calls for the development of new organ system support technologies and the use of methods capable of sorbing microorganisms and their toxins in the area of inflammation.

Keywords

For citations:

Lazareva O.V., Barinov S.V., Shifman E.M., Popova L.D., Shkabarnya L.L., Tirskaya Yu.I., Kadtsyna T.V., Chulovsky Yu.I. Characterization of Pathogenic Microflora Causing Suppurative Septic Postpartum Complications: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2023;30(3):15-24. https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2023-30-3-15-24

INTRODUCTION

Despite the development of new medical technologies, one of the main problems of modern obstetrics is associated with a high rate of suppurative septic postpartum complications, which remains the leading cause of maternal mortality [1]. The likelihood of infectious complications arising in the postpartum period is determined by the following factors: nature of pathogenic microflora; general health of the woman; presence of chronic diseases; complications of pregnancy and delivery; amount of blood loss; operative delivery [2]. The massive use of antibiotics and the resistance developed by microorganisms constitute the most important issues with which we have been dealing in recent decades in the treatment of inflammatory complications [3].

The severity of suppurative septic postpartum diseases is determined by the following three main aspects: infection, the body’s response to the infection, and organ dysfunction. A wide range of pathogens can cause life-threatening reactions in a large number of organs; hence, suppurative septic complications have diverse clinical manifestations. Physiological, immunological, and mechanical changes during pregnancy make women more susceptible to infections as compared to nonpregnant women, specifically in the postpartum period [4].

Clinical manifestations of suppurative septic postpartum complications can vary from mild to severe forms and do not always correspond to the infection activity, which often leads to late diagnosis and generalization of the process [5]. Following operative delivery, suppurative septic complications have a more severe course as compared to natural childbirth. Recent years have seen a steady increase in the operative delivery rate worldwide, which is associated with the perinatal focus of obstetrics. Despite improvements in the surgical procedure, as well as the use of modern suture materials and antibacterial drugs, the cesarean section remains a complex operation posing an additional risk of postoperative postpartum complications, among which inflammatory processes prevail. The risk of infectious complications arising following a cesarean section is 20 times higher than following natural childbirth [6][7]. Following a cesarean section, the most common septic complication is endometritis, which, with the infectious process development, can lead to postoperative suture failure, parametritis, pelvic peritonitis, and sepsis [8].

In recent decades, the structure of pathogens responsible for suppurative septic postpartum diseases has changed, which is associated with the selection of microorganisms under the influence of antibiotics. In the “pre-antibiotic” era, Streptococcus was replaced by Staphylococcus aureus due to the active use of benzylpenicillin. Subsequently, the use of β-lactam antibiotics increased the etiological significance of Gram-negative microorganisms. In most cases, postpartum endometritis develops as a result of exposure to aerobic organisms, both Gram-positive (Group A β-hemolytic Streptococcus, coagulase-positive Staphylococcus aureus, Group B Streptococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Enterococcus faecalis, and Listeriamono cytogenes), and Gram-negative (Escherichia coli, Haemophilus influenza, Klebsiella species, Proteus species, Pseudomonas species, Serrata species, Gardnerella vaginalis, and Bacteroides fragilis). Less commonly, endometritis develops due to sexually transmitted infections such as Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis [9].

The irrational use of antibiotics in obstetric practice has created conditions for the selection of strains with acquired resistance to antibiotics from several pharmacological groups used to treat obstetric patients with septic complications: amoxicillin, amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, piperacillin/tazobactam, and gentamicin. The data of recent years indicate an increase in the etiological ignify cance of the Enterococcus genus due to the acquired resistance to cephalosporins [9][10].

Thus, despite a considerable amount of information on the etiology, as well as clinical and pathogenetic variants, of suppurative septic postpartum complications, this issue requires continuous study and analysis.

The study aims to characterize pathogenic microflora isolated in obstetric patients with suppurative septic postpartum complications.

METHODS

Study design

A retrospective cohort study (analysis of medical records) of 123 obstetric patients with suppurative septic postpartum complications was conducted. Anamnestic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected.

Study conditions

The study was conducted at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2 of the Omsk State Medical University (Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation) and the Department of Gynecology of the Omsk Regional Clinical Hospital. The analysis of complications associated with operative delivery was performed according to the medical records of inpatients (medical history), i.e., obstetric patients with suppurative septic postpartum complications, treated from January 2013 to December 2022.

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Presence of a suppurative septic complication associated with operative delivery, confirmed by clinical and laboratory diagnostic methods within 42 days of delivery.

Exclusion criteria

Active course of specific infectious (tuberculosis; viral hepatitis B and C) and venereal (syphilis; gonorrhea) diseases; malignant tumors; severe extragenital pathology.

Description of the eligibility criteria (diagnostic criteria)

Suppurative septic postpartum complications were diagnosed following the criteria specified in the clinical guidelines of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation Septic Complications in Obstetrics as of January 10, 2017. As reflected in the medical records, the results of the bacteriological examination of uterine cavity aspirate and abdominal secretion in obstetric patients were entered in the research database.

Selection of group members

According to the analysis of 7204 labor and delivery records of cesarean section patients, a total of 123 obstetric patients were found to develop suppurative septic postpartum complications within 42 days of delivery: endometritis, failure of the postoperative suture, parametritis, and pelvic peritonitis (ICD-10 O86.8 Other Specified Puerperal Infections; O86.0 Infection of Obstetric Surgical Wound). These postpartum infections were grouped to characterize dominant pathogenic microflora associated with different types of complications and to determine its resistance to antibacterial drugs, which should facilitate a targeted rational therapy. On the basis of anamnestic, clinical, laboratory, and instrumental data, the following three groups were formed: Group A — uncomplicated course of postpartum endometritis; Group B — complicated forms of postpartum endometritis: B1 — local complications (suture failure following cesarean section; parametritis), B2 — pelvic peritonitis; Group C — septic complications associated with critical obstetric conditions (massive obstetric bleeding; severe preeclampsia).

Target parameters in the study

Main parameter in the study

The pathogenic microflora of uterine and abdominal cavities in obstetric patients with various forms of suppurative septic complications was characterized on the first day of admission to the hospital, prior to the start of empiric antimicrobial therapy.

Additional parameters in the study

In order to ascertain the etiological significance of microorganisms in the development of postpartum endometritis, the quantitative indicator was determined. The extent of contamination was assessed using the following criteria: low degree — 102–103 CFU/mL; medium — 104 CFU/mL; high — 105 CFU/mL and higher.

Methods for measuring the target parameters

We analyzed 171 bacteriologic examination results of 123 obstetric patients with various forms of suppurative septic complications. Material from the uterine cavity was collected under aseptic conditions using a sterile single-use aspiration device pre-inserted into the cervical canal, which prevented sample contamination by cervical and vaginal microbiota (n = 103). For aspiration, sterile, disposable silicone catheters were used inserted into the cervical canal, which eliminated the possibility of sample contamination by vaginal and cervical microflora. Vacuum aspiration was performed using a sterile disposable syringe, with material placed in a sterile container with a transport medium. Abdominal material from the wound area was sampled intraoperatively (n = 68). In the bacteriological laboratory, the aerobic and microaerophilic flora were isolated via quantitative inoculation on 5% blood agar. Enterobacteriaceae and staphylococci were isolated using Endo agar and egg yolk salt agar, respectively. Candida spp. were grown on Sabouraud Agar. Oblate anaerobes were cultured on Schaedler agar supplemented with 5% blood or in a thioglycollate medium. The isolated microorganisms were identified using a MicroTax bacteriological analyzer (Austria; since 2018, Vitek2 Compact, France) and routine methods. The species and genus of microorganisms were determined, as well as the extent of contamination with the pathogen. In order to determine the sensitivity of microorganisms to antibacterial drugs, a disk diffusion method was used as per the recommendations of the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST).

Variables (predictors, confounders, and effect modifiers)

The study considered potential risk predictors: anemia; acute and exacerbation of chronic infectious diseases during pregnancy; chorioamnionitis; cesarean section in the setting of vaginitis; long interval between membrane rupture and delivery; increase in the number of repeat cesarean sections; interval between deliveries of less than one year; fetal hypoxia; presence of meconium amniotic fluid.

Statistical procedures

Principles behind sample size determination

The sample size was not determined in advance.

Statistical methods

Mathematical and statistical data processing was performed using licensed Microsoft Office Excel 2013 and Statistica 10 (StatSoft Inc., USA). Nominal indicators are presented in absolute and relative values (%). In order to compare nonparametric nominal data in two independent groups, Pearson’s chi-squared test was calculated with p-value determination. Differences were considered statistically significant at р < 0.05.

RESULTS

Sampling

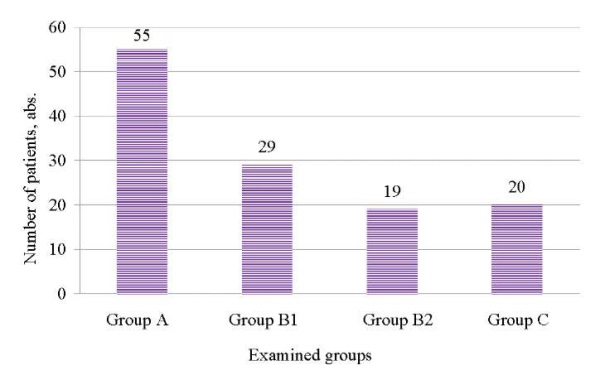

Of 7204 women, 1.7% (n = 123) developed suppurative septic complications following cesarean section procedures: 44.7% (n = 55/123) — postpartum endometritis; 39.0% (n = 48/123) — complications of postpartum endometritis (23.6% (n = 29/123) — suture failure and parametritis; 15.4% (n = 19/123) — pelvic peritonitis); 16.3% (n = 20/123) — septic complications following critical obstetric conditions (massive obstetric bleeding; preeclampsia) (Fig.1).

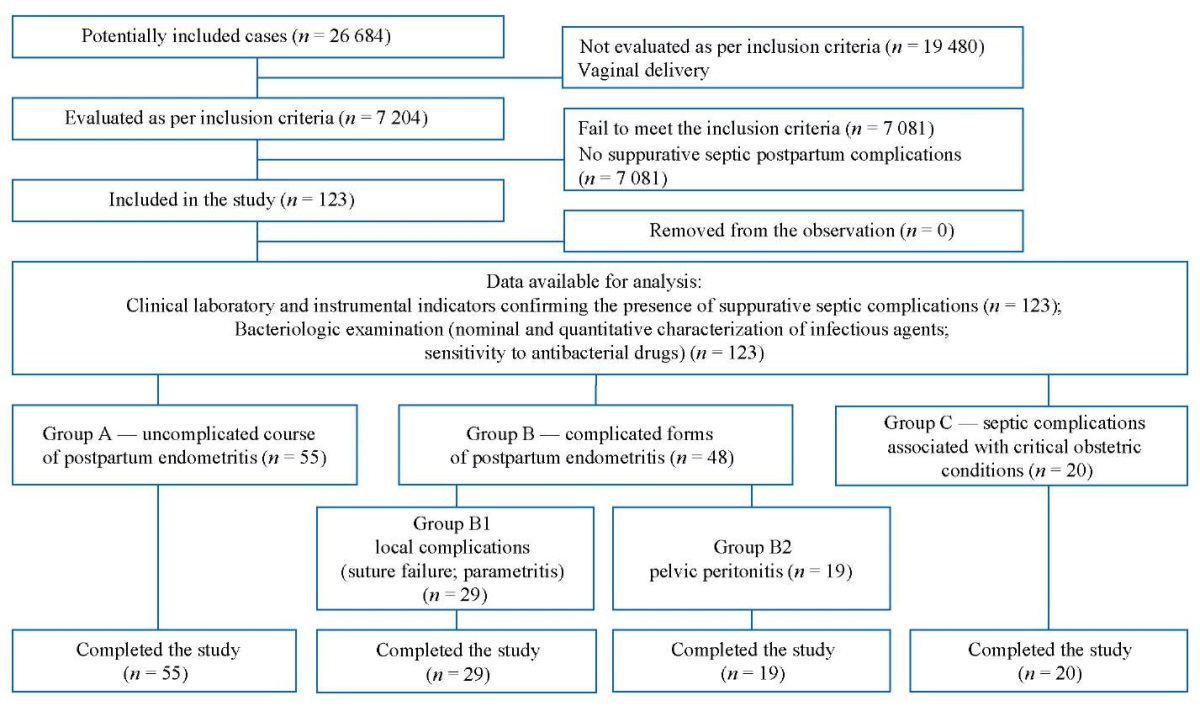

The block diagram of the study design is presented in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1. Structure of suppurative septic postpartum complications following a cesarean section.

Note: The figure was created by the authors.

Рис. 1. Структура гнойно-септических послеродовых осложнений после операции кесарева сечения.

Примечание: рисунок выполнен авторами.

Fig. 2. Block diagram of the study design.

Note: The block diagram was created by the authors (as per STROBE recommendations).

Рис. 2. Блок-схема дизайна исследования.

Примечание: блок-схема выполнена авторами (согласно рекомендациям STROBE).

Characteristics of the study sample

The main anamnestic, clinical, and technical factors affecting delivery are presented in Table 1.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients included in the study (n; %)

Таблица 1. Характеристика пациенток, включенных в исследование (n; %)

|

Parameters |

SSC following a cesarean section, n = 123 |

No SSC following a cesarean section, n = 7204 |

p * р < 0.05 |

|

Average age (years) |

28±4.8 |

27±3.6 |

– |

|

Gestational age (weeks) |

35±2.1 |

38±1.6 |

– |

|

Gestational age of <35 weeks |

31 (25.2) |

360 (4.9) |

<0.001* |

|

BMI |

29.5±2.1 |

27±1.7 |

– |

|

Previous cesarean delivery |

25 (20.3) |

920 (12.8) |

0.02* |

|

History of abortions |

37 (30.1) |

2140 (29.7) |

0.99 |

|

Chronic somatic and gynecologic pathology |

|||

|

Chronic extragenital infectious diseases |

81 (65.8) |

4234 (58.8) |

0.14 |

|

Chronic anemia |

56 (45.5) |

867 (12.0) |

0.25 |

|

Gynecological diseases |

35 (28.5) |

2875 (39.9) |

0.01* |

|

Course of pregnancy |

|||

|

Threatened miscarriage |

38 (30.9) |

2154 (29.9) |

0.89 |

|

Placental disorders |

18 (14.6) |

1453 (20.2) |

0.16 |

|

Anemia of pregnancy |

92 (74.8) |

4105 (56.9) |

<0.001* |

|

Preeclampsia |

34 (27.6) |

923 (12.8) |

<0.001* |

|

Acute respiratory infections |

87 (70.7) |

5870 (81.5) |

0.004* |

|

Vaginitides |

97 (78.9) |

6457 (89.6) |

<0.001* |

|

Gestational diabetes |

5 (4.1) |

231 (3.2) |

0.78 |

|

Chorioamnionitis |

6 (4.9) |

121 (1.7) |

0.02* |

|

Caesarean section is performed |

|||

|

For emergency indications |

102 (82.9) |

3457 (47.9) |

<0.001* |

|

As an elective surgery |

21 (17.1) |

3747 (52.1) |

<0.001* |

|

Indications for a caesarean section |

|||

|

Fetal distress |

39 (31.7) |

2032 (28.2) |

0.45 |

|

Labor abnormalities |

18 (14.6) |

957 (13.3) |

0.76 |

|

Clinically contracted pelvis |

11 (8.9) |

832 (11.5) |

0.45 |

|

Preeclampsia |

19 (15.4) |

634 (8.8) |

0.02* |

|

Placental abruption |

15 (12.2) |

284 (3.9) |

<0.001* |

|

Placenta previa |

4 (3.3) |

654 (9.1) |

0.04* |

|

Uterine scar |

16 (13.0) |

1811 (25.1) |

0.003* |

|

Specifics of the procedure |

|||

|

Duration (min.) |

79±23 |

38±18 |

– |

|

Blood Loss (mL) |

860±320 |

540±120 |

– |

|

Blood transfusion |

46 (37.4) |

760 (10.5) |

<0.001* |

Notes: The table was compiled by the authors; * — statistically significant difference between groups (р<0.05); Abbreviations: BMI — body mass index; SSC — suppurative septic complications

Примечания: таблица составлена авторами; * — статистически значимые различия между группами (р < 0,05). Сокращения: ИМТ — индекс массы тела; ГСО — гнойно-септические осложнения.

Main study results

We analyzed the microflora isolated in patients with suppurative septic postpartum complications in 2013–2022. Comparative analysis results for the periods of 2013–2017 and 2018–2022 are presented in Table 2.

Table 2. Results of bacteriological examination in patients with suppurative septic postpartum complications

Таблица 2. Результаты бактериологического исследования пациенток с гнойно-септическими осложнениями послеродового периода

|

Verified pathogens |

2013–2017, n = 65 |

2018–2022, n = 58 |

chi-squared test |

Level of significance р |

||

|

abs. |

% |

abs. |

% |

|||

|

Staphylococcus epidermidis, n = 63 |

40 |

61.54 |

23 |

39.66 |

5.87 |

0.016* |

|

Enterococcus faecalis, n = 48 |

35 |

53.85 |

13 |

22.41 |

12.77 |

<0.001* |

|

Escherichia coli, n = 48 |

23 |

35.38 |

25 |

43.10 |

0.77 |

0.38 |

|

Enterococcus faecium, n = 39 |

20 |

30.77 |

9 |

15.51 |

3.96 |

0.05* |

|

Acinetobacter baumannii, n = 15 |

9 |

13.85 |

6 |

10.34 |

0.35 |

0.55 |

|

Candida albicans, n = 9 |

6 |

9.23 |

3 |

5.17 |

0.74 |

0.39 |

|

Klebsiella pneumoniae, n = 15 |

9 |

13.85 |

6 |

10.34 |

0.35 |

0.55 |

|

Staphylococcus haemolyticus, n = 11 |

5 |

7.69 |

6 |

10.34 |

0.26 |

0.61 |

|

Corynebacterium amycolatum, n = 6 |

2 |

3.08 |

4 |

6.90 |

0.96 |

0.33 |

|

Peptostreptococcus spp., n = 2 |

2 |

3.08 |

– |

– |

1.81 |

0.18 |

|

Streptococcus anginosus, n = 2 |

2 |

3.08 |

– |

– |

1.81 |

0.18 |

|

Staphylococcus warneri, n = 3 |

2 |

3.08 |

1 |

1.72 |

0.24 |

0.63 |

|

Pantoea agglomerans, n = 1 |

1 |

1.54 |

– |

– |

0.90 |

0.34 |

|

Pseudomonas aeruginosa, n = 1 |

1 |

1.54 |

– |

– |

0.90 |

0.34 |

Notes: The table was compiled by the authors; * — statistically significant difference between groups (р < 0.05).

Примечания: таблица составлена авторами; * — статистически значимая разница между группами (р < 0,05).

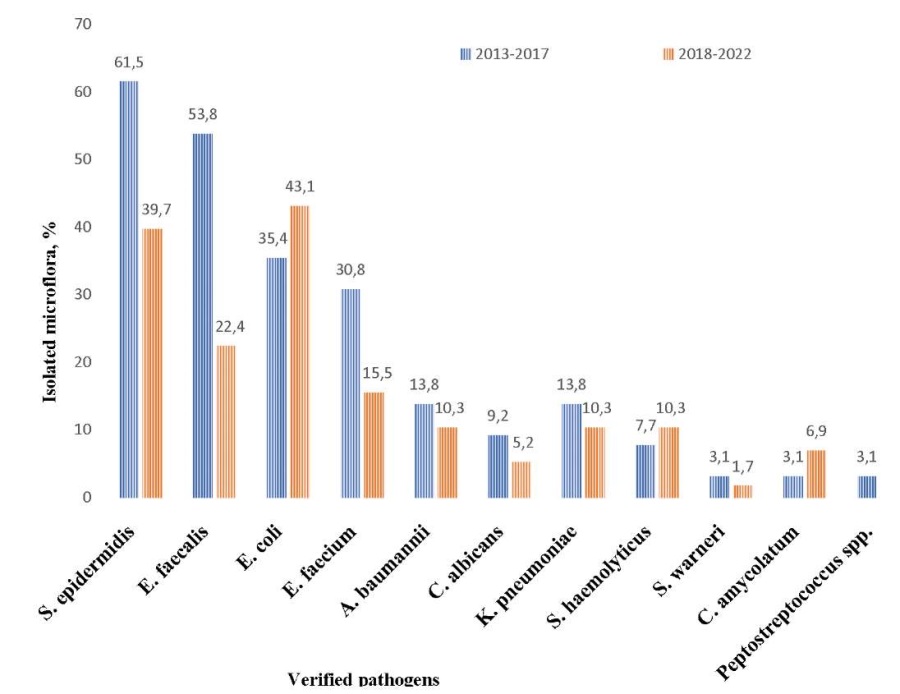

In 2013–2017, S. epidermidis dominated the isolated pathogenic microflora, followed by E. faecalis, then by E. coli and E. faecium, whereas in 2018–2022, S. epidermidis ranked first, E. coli second, and E. faecalis third. According to Fig. 3, a statistically significant decrease was observed in 2018–2022 in the isolation rate of S. epidermidis (p = 0.016) and E. faecalis (p < 0.001), as well as 2.0 times decrease in E. faecium, 1.3 times decrease in А. baumannii, and 1.8 times decrease in С. albicans. However, an increase was noted in the isolation rate of E. coli (1.2 times), S. haemolyticus (1.3 times), and C. аmycolatum (2.2 times).

Fig. 3. Comparative analysis of pathogenic microflora for 2013–2017 and 2018–2022.

Note: The figure was created by the authors.

Рис. 3. Сравнительный анализ патогенной микрофлоры за 2013–2017 и 2018–2022 гг.

Примечание: рисунок выполнен авторами.

The analysis of pathogenic microflora resistance to antibacterial drugs yielded the following results. S. epidermidis exhibited resistance to cephalosporins (30.16%), clindamycin (22.22%), aminopenicillins (11.11%), and carbapenems (11.11%). E. faecalis was found to be insensitive to fluoroquinolones (33.33%), aminopenicillins (6.25%), β-lactamase-resistant penicillins (amoxicillin-clavulanate) (4.17%), and cephalosporins (4.17%). E. coli was found to be resistant to cephalosporins (65.91%), β-lactamase-resistant penicillins (amoxicillin-clavulanate) (40.91%), aminoglycosides (27.23%), penicillins (18.18%), fluoroquinolones (15.91%), and carbapenems (2.27%). E. faecium was found to be resistant to aminopenicillins (64.10%), fluoroquinolones (50.0%), carbapenems (20.51%), vancomycin (7.69%), and β-lactamase-resistant penicillins (amoxicillin-clavulanate) (5.13%). А.baumannii exhibited resistance to fluoroquinolones, cephalosporins, and carbapenems in 100% of cases and to aminoglycosides in 84.2% of cases.

An analysis of pathogenic microflora isolated in various forms of septic complications is presented in Table 3.

Table 3 indicates a statistically significantly higher isolation rate of S. еpidermidis, E. faecium, and A. baumannii in the setting of pelvic peritonitis as compared to uncomplicated endometritis. In the case of septic complications arising due to critical obstetric conditions, the isolation rate is higher for S. еpidermidis, E. coli, E. faecium, A. baumannii, and K. рneumoniae.

Table 3. Results of bacteriological examination in obstetric patients with various forms of suppurative septic postpartum complications

Таблица 3. Результаты бактериологического исследования родильниц при различных формах гнойно-септических осложнений послеродового периода

|

Verified pathogens |

Group А, n = 55 % |

Group В1, n = 29 % |

Group В2, n = 19 % |

chi-squared test, рА-В2 value |

Group С, n = 20 % |

chi-squared test, рА-С value |

|

S. epidermidis |

25.45 |

75.86 |

68.42 |

<0.001* |

70.00 |

<0.001 |

|

E. faecalis |

32.73 |

58.62 |

36.84 |

0.74 |

30.00 |

0.82 |

|

E. coli |

34.55 |

55.17 |

57.90 |

0.07 |

10.00 |

0.04* |

|

E. faecium |

10.91 |

62.07 |

36.84 |

0.01* |

40.00 |

0.005* |

|

A. baumannii |

1.82 |

17.24 |

15.90 |

0.02* |

30.00 |

<0.001* |

|

C. albicans |

3.64 |

1.82 |

15.90 |

0.07 |

15.00 |

0.08 |

|

K. pneumoniae |

7.27 |

6.90 |

21.05 |

0.09 |

25.00 |

0.04* |

|

S. haemolyticus |

10.91 |

10.34 |

– |

0.13 |

10.00 |

0.91 |

|

P. agglomerans |

– |

– |

– |

5.00 |

0.09 |

|

|

С. amycolatum |

7.27 |

6.90 |

– |

0.23 |

– |

0.22 |

|

Peptostreptococcus spp. |

– |

– |

10.53 |

0.01* |

– |

– |

|

S. anginosus |

1.82 |

1.82 |

– |

0.55 |

– |

0.54 |

|

S. warneri |

1.82 |

6.90 |

– |

0.55 |

– |

0.54 |

|

P. aeruginosa |

– |

– |

– |

5.00 |

0.09 |

Notes: The table was compiled by the authors; рА-В2 — p-value between Groups A and B2; рА-С — p-value between Groups A and C; * — statistically significant difference between groups (р < 0.05).

Примечания: таблица составлена авторами, рА-В2 — значение критерия р между группой А и В2; рА-С — значение критерия р между группой А и В2; * — статистически значимая разница между группами (р < 0,05).

Additional study parameters

When assessing the extent of contamination, a high titer of microorganisms was found in 60.53% of cases, an average titer in 11.84%, and a low titer in 27.63% of cases.

DISCUSSION

Main findings of the study

This study conducted to provide a qualitative and nominal characterization of pathogenic microflora causing various forms of suppurative septic postpartum complications, as well as to estimate its sensitivity to the main types of antibacterial drugs used in clinical practice, will improve the treatment of obstetric patients with this pathology by enabling a choice of adequate therapy as early as at diagnosis, prior to bacteriological examination, and expand the search for new treatment methods affecting pathogenic microflora in the area of infection.

Research limitations

The limitation of the retrospective study is associated with a certain “bias” of documentation. Also, this is a study using a small number of patients, which may affect the final results.

Interpretation of the study results

The study showed that in the pathogenic microflora causing suppurative septic postpartum complications, S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, and E. faecium predominate. In 2018–2022, a change in the pathogen occurred, with E. coli taking second place instead of E. faecalis. These microorganisms have held leading positions for the last 5–7 years, as confirmed by several studies [10][11][12][13]. Their activation is attributed to a decrease in the body’s immune responsiveness during pregnancy, childbirth, and surgical intervention [14][15].

We assume that the statistically significant decrease in the isolation rate of S. epidermidis (p = 0.016), E. faecalis (p < 0.001), and E. faecium (p = 0.05) in 2018–2022 is associated with the widespread use of β-lactamase-resistant penicillins (amoxicillin-clavulanate) and carbapenems for the treatment of obstetric patients with suppurative septic postpartum complications, to which pathogens still have low resistance. However, medicine faces a serious problem related to the biological resistance of bacteria to antibiotics, necessitating the search for new methods affecting the area of infection [13][16][17]. The microbial agent analysis according to the type of suppurative septic complication showed that S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, and E. faecium predominate, irrespective of the complication. Literature data indicate a key role of Gram-positive bacteria in the development of obstetric peritonitis, as well as associations of Gram-positive and Gram-negative microflora in a significant proportion of female patients [18][19][20][21], which is confirmed by this study. When analyzing the extent of contamination with the microflora, over half of the obstetric patients we examined (60.53%) were found to have a high titer. The extent of contamination depends on the obstetric patient’s health status, the characteristics of microorganisms, and their virulence, which enables the differentiation of pathogens from contaminating microorganisms [22]. Under current conditions, an increase is observed in the rate of complications caused by Gram-negative non-fermentative bacteria (P. aeruginosa and Acinetobacter spp.), which cause sepsis in intensive care unit patients [23]. In this study, P. аeruginosa was found only in women with septic complications due to critical obstetric conditions (5.00%). In the examined obstetric patients, the isolation rate of A.baumannii was 8.7 times higher in the case of pelvic peritonitis (p = 0.02). In the case of complications due to critical obstetric complications, it was 16.5 times higher (p < 0.001) as compared to uncomplicated endometritis. An A. baumannii infection can lead to a fatal outcome from a toxic shock syndrome and multiple organ failure [11]. An extremely unfavorable phenomenon is pan-resistance, i.e., resistance to all antibacterial drugs recommended for therapy [24][25]. First of all, this applies to A. baumannii which has an extremely high ability to express genes that implement resistance mechanisms, as shown in this study. Of particular interest here is the isolation rate of K. рneumoniae, which was 2.9 times higher in patients with obstetric peritonitis and 3.4 times higher following critical obstetric conditions as compared to uncomplicated endometritis. The presence of these microorganisms is often accompanied by severe septic complications.

The irrational use of antibiotics in clinical practice constitutes the main condition for the emergence of multidrug-resistant bacteria or even bacteria completely resistant to any drugs, the so-called ESKAPE superbugs [9][26].

CONCLUSION

Over the past decade, specific pathogens (specifically S. epidermidis, E. faecalis, E. coli, and E. faecium) have been shown to play a key role in the etiology and development of suppurative septic postpartum diseases. The irrational use of antibiotics in medicine creates conditions for the emergence of multidrug resistance. This calls for the introduction of new organ-system support technologies, appropriate infection control, and the development of new methods, including the widespread use of formed carbon sorbents with various modifiers capable of sorbing microorganisms and their toxins in the area of inflammation.

References

1. Ivannikov N.Yu., Mitichkin A.E., Dimitrova V.I., Slyusareva O.A., Khlynova S.A., Dobrokhotova Yu.E. Modern approaches to the treatment of postpartum purulent-septic diseases. Meditsinsky Sovet. 2019; 7: 58–69 (In Russ.). DOI: 10.21518/2079-701X-2019-7-58-69

2. Axelsson D., Brynhildsen J., Blomberg M. Postpartum infection in relation to maternal characteristics, obstetric interventions and complications. J. Perinat. Med. 2018; 46(3): 271–278. DOI: 10.1515/jpm-2016-0389

3. Contro E., Jauniaux E. Puerperal sepsis: what has changed since Semmelweis’stime. BJOG. 2017; 124(6): 936. DOI: 10.1111/1471-0528.14377

4. Bonet M., Nogueira Pileggi V., Rijken M.J., Coomarasamy A., Lissauer D., Souza J.P., Gülmezoglu A.M. Towards a consensus definition of maternal sepsis: results of a systematic review and expert consultation. Reprod. Health. 2017; 14(1): 67. DOI: 10.1186/s12978-017-0321-6

5. Woodd S.L., Montoya A., Barreix M., Pi L., Calvert C., Rehman A.M., Chou D., Campbell O.M.R. Incidence of maternal peripartum infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2019; 16(12): e1002984. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002984

6. Singh N., Sethi A. Endometritis — Diagnosis,Treatment and its impact on fertility — A Scoping Review. JBRA Assist.Reprod. 2022; 26(3): 538–546. DOI: 10.5935/1518-0557.20220015

7. Shi M., Chen L., Ma X., Wu B. The risk factors and nursing countermeasures of sepsis after cesarean section: a retrospective analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2022; 22(1): 696. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-022-04982-8

8. Zeng S., Liu X., Liu D., Song W. Research update for the immune microenvironment of chronic endometritis. J. Reprod. Immunol. 2022; 152: 103637. DOI: 10.1016/j.jri.2022.103637

9. Zhilinkova N.G. Modern ideas about puerperal infections due to antibacterial resi the stent and the end of the antibiotic era. Obstetrics and Gynecology: News, Opinions, Training. 2019; 7(3): 70–75 (In Russ.). DOI: 10.24411/2303-9698-2019-13010

10. Abu Shqara R., Bussidan S., Glikman D., Rechnitzer H., Lowenstein L., Frank Wolf M. Clinical implications of uterine cultures obtained during urgent caesarean section. Aust. N Z J Obstet. Gynaecol. 2022. DOI: 10.1111/ajo.13630

11. Zejnullahu V.A., Isjanovska R., Sejfija Z., Zejnullahu V.A. Surgical site infections after cesarean sections at the University Clinical Center of Kosovo: rates, microbiological profile and risk factors. BMC Infect. Dis. 2019; 19(1): 752. DOI: 10.1186/s12879-019-4383-7

12. Li L., Cui H. The risk factors and care measures of surgical site infection after cesarean section in China: a retrospective analysis. BMC Surg. 2021; 21(1): 248. DOI: 10.1186/s12893-021-01154-x

13. Ahmed S., Kawaguchiya M., Ghosh S., Paul S.K., Urushibara N., Mahmud C., Nahar K., Hossain M.A., Kobayashi N. Drug resistance and molecular epidemiology of aerobic bacteria isolated from puerperal infections in Bangladesh. Microb.Drug. Resist. 2015; 21(3): 297–306. DOI: 10.1089/mdr.2014.0219

14. Sáez-López E., Guiral E., Fernández-Orth D., Villanueva S., Goncé A., López M., Teixidó I., Pericot A., Figueras F., Palacio M., Cobo T., Bosch J., Soto S.M. Vaginal versus Obstetric Infection Escherichia coli Isolates among Pregnant Women: Antimicrobial Resistance and Genetic Virulence Profile. PLoS One. 2016; 11(1): e0146531. DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0146531

15. Malmir M., Boroojerdi N.A., Masoumi S.Z., Parsa P. Factors Affecting Postpartum Infection: A Systematic Review. Infect. Disord.Drug.Targets. 2022; 22(3): e291121198367. DOI: 10.2174/1871526521666211129100519

16. Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine (SMFM). Electronic address: pubs@smfm.org; Plante L.A., Pacheco L.D., Louis J.M. SMFM Consult Series #47: Sepsis during pregnancy and the puerperium. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019; 220(4): B2–B10. DOI: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.01.216

17. Faure K., Dessein R., Vanderstichele S., Subtil D. Endométrites du post-partum. RPC infections génitaleshautes CNGOF et SPILF [Postpartum endometritis: CNGOF and SPILF Pelvic Inflammatory Diseases Guidelines]. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2019; 47(5): 442–450. French. DOI: 10.1016/j.gofs.2019.03.013

18. Barinov S.V., Lazareva O.V., Medyannikova I.V., Tirskaya Yu.I., Kadtsyna T.V., Leont’eva N.N., Shkabarnya L.L., Chulovskiy Yu.I., Gritsyuk M.N. On the issue of performing organ-preserving operations for postpartum endometritis after cesarean section.Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021; 10: 67–75 (In Russ.). DOI: 10.18565/aig.2021.10.76-84

19. Phillips C., Walsh E. Group A Streptococcal Infection During Pregnancy and the Postpartum Period. Nurs. Womens. Health. 2020; 24(1): 13–23. DOI: 10.1016/j.nwh.2019.11.006

20. Getaneh T., Negesse A., Dessie G. Prevalence of surgical site infection and its associated factors after cesarean section in Ethiopia: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2020; 20(1): 311. DOI: 10.1186/s12884-020-03005-8

21. Pavoković D., Cerovac A., Ljuca D., Habek D. Post-Cesarean Peritonitis Caused by Hysterorrhaphy Dehiscence with Puerperal Acute Abdomen Syndrome. Z. Geburtshilfe. Neonatol. 2020; 224(6): 374–376. DOI: 10.1055/a-1203-0983

22. Smirnova S.S., Egorov I.A., Golubkova A.A. Purulent-septic infections in puerperas. Part 2. Clinical and pathogenetic characteristics of nosological forms, etiology and antibiotic resistance (literature review). Journal of microbiology, epidemiology and immunobiology. 2022; 99(2): 244–259. DOI: 10.36233/0372-9311-227

23. Bitew Kifilie A., Dagnew M., Tegenie B., Yeshitela B., Howe R., Abate E. Bacterial Profile, Antibacterial Resistance Pattern, and Associated Factors from Women Attending Postnatal Health Service at University of Gondar Teaching Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Int. J. Microbiol. 2018; 2018: 3165391. DOI: 10.1155/2018/3165391

24. Gelfand B.R., Rudnov V.A., Galstyan G.M., Gelfand E.B., Zabolotskikh I.B., Zolotukhin K.N., Kulabukhov V.V., Lebedinskiy K.M., Levit A.L., Nekhaev I.V., Nikolenko A.V., Protsenko D.N., Shchegolev A.V., Yaroshetskiy A.I. Sepsis: terminology, pathogenesis, clinical diagnostic conception. Voprosy Ginekologii, Akušerstva i Perinatologii. 2017; 16(1): 64–72 (In Russ.). DOI: 10.20953/1726-1678-2017-1-64-72

25. Igwemadu G.T., Eleje G.U., Eno E.E., Akunaeziri U.A., Afolabi F.A., Alao A.I., Ochima O. Single-dose versus multiple-dose antibiotics prophylaxis for preventing caesarean section postpartum infections: A randomized controlled trial. Womens Health (Lond). 2022; 18: 17455057221101071. DOI: 10.1177/17455057221101071

26. Moulton L.J., Lachiewicz M., Liu X., Goje O. Endomyometritis after cesarean delivery in the era of antibiotic prophylaxis: incidence and risk factors. J. Matern. Fetal.Neonatal.Med. 2018; 31(9): 1214–1219. DOI: 10.1080/14767058.2017.1312330

About the Authors

O. V. LazarevaRussian Federation

Oksana V. Lazareva — Cand. Sci. (Med.), Assoc. Prof. of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2.

Lenina str., 12, Omsk, 644099

S. V. Barinov

Russian Federation

Sergey V. Barinov — Dr. Sci. (Med.), Prof., Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2.

Lenina str., 12, Omsk, 644099

E. M. Shifman

Russian Federation

Efim M. Shifman — Dr. Sci. (Med.), Prof. of the Department of Anesthesiology and Resuscitation.

Shchepkina str., 61/2, Moscow, 129090

L. D. Popova

Russian Federation

Larisa D. Popova — Head of the Bacteriological Laboratory.

Berezovaya str., 3, Omsk, 644111

L. L. Shkabarnya

Russian Federation

Lyudmila L. Shkabarnya — Head of the Department of Gynecology.

Berezovaya str., 3, Omsk, 644111

Yu. I. Tirskaya

Russian Federation

Yulia I. Tirskaya — Dr. Sci. (Med.), Assoc. Prof., Prof. of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University.

Lenina str., 12, Omsk, 644099

T. V. Kadtsyna

Russian Federation

Tatyana V. Kadtsyna — Cand. Sci. (Med.), Assoc. Prof. of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University.

Lenina str., 12, Omsk, 644099

Yu. I. Chulovsky

Russian Federation

Yury I. Chulovsky — Cand. Sci. (Med.), Assoc. Prof. of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology No. 2, Omsk State Medical University.

Lenina str., 12, Omsk, 644099

Supplementary files

Review

For citations:

Lazareva O.V., Barinov S.V., Shifman E.M., Popova L.D., Shkabarnya L.L., Tirskaya Yu.I., Kadtsyna T.V., Chulovsky Yu.I. Characterization of Pathogenic Microflora Causing Suppurative Septic Postpartum Complications: a Retrospective Cohort Study. Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2023;30(3):15-24. https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2023-30-3-15-24

JATS XML