Scroll to:

Differential use of various types of pessaries in isthmic-cervical insufficiency for prevention of preterm birth: A randomized prospective trial

https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2024-31-5-15-25

Abstract

Background. Obstetric pessary comprises one of the methods for treatment of isthmic-cervical insufficiency. Despite the variety of pessaries produced, the common purpose of their use consists in preventing premature birth. Various types of pessaries correct different cervical parameters, which is not always taken into account by doctors when choosing a pessary and reduces their potential effectiveness. Objective. To substantiate a differentiated approach to the selection of pessary type for correcting isthmic-cervical insufficiency and preventing preterm birth based on the evaluation of cervical parameters. Methods. A randomized prospective study enrolled 90 pregnant women diagnosed with isthmic-cervical insufficiency (ICD-10 code — О.34.3) at 19–24 weeks of gestation. Of these, 41 women underwent correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency with an obstetric unloading pessary and 49 women — with a perforated cervical pessary. Transvaginal ultrasound cervicometry evaluated the parameters of the cervix before correcting isthmic-cervical insufficiency and in dynamics (once every 4 weeks) after inserting various types of pessaries. Statistical data processing was carried out using Statistica 10.0 (StatSoft, Tulsa, USA) and MedCalc 10.2.0.0 (MedCalc, Mariakerke, Belgium). The differences were considered to be statistically significant at p <0.05. Results. Inserting an obstetric unloading pessary in isthmic-cervical insufficiency decreased the uterocervical angle from 115 (110; 130)° to 100 (90; 115)° (p = 0.021). A decrease in the uterocervical angle was observed during 16-week-use of obstetric unloading pessary. After insertion of perforated cervical pessaries, the length of the closed part of the cervical region increased from 23 (21; 24) mm to 25 (21; 27) mm (p = 0.009) for a period of 4 weeks with a subsequent decrease in this parameter. The effectiveness of both types of pessaries in preventing preterm birth was found to be identical. Urgent delivery occurred in 61% of cases of using an obstetric unloading pessary and in 64.7% of cases of using a perforated cervical pessary (p = 0.993). The gestational age at preterm birth against the background of the use of obstetric unloading pessaries and perforated cervical pessaries was found comparable and amounted to 247 (230; 253) days and 245 (225; 254) days, respectively (p = 0.870). Conclusion. A differentiated approach to selecting a type of pessary for the prevention of premature birth in isthmic-cervical insufficiency is determined by the initial ultrasound parameters of the cervix. Thus, an increase in the uterocervical angle serves as an indication for an obstetric unloading pessary, while a shortened part of the cervical region without an increase in the utero-cervical angle determines the use of a perforated cervical pessary. Additional dynamic ultrasound control after inserting pessaries of any type allows such complications as pessary displacement, cervical edema, amniotic fluid sludge, prolapse of fetal membranes in the vagina, and increased myometrial tone to be timely diagnosed and corrected, thereby increasing the effectiveness of using pessaries.

For citations:

Zakharenkova T.N., Kaplan Yu.D., Zanko S.N., Kovalevskaya T.N. Differential use of various types of pessaries in isthmic-cervical insufficiency for prevention of preterm birth: A randomized prospective trial. Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2024;31(5):15-25. https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2024-31-5-15-25

INTRODUCTION

Every year, 15 million premature infants are born worldwide and about 1 million children under 5 years of age die from a cause related to preterm birth [1]. The global incidence of preterm births ranges from 4 to 18% of the total number of births. In the Republic of Belarus, according to the reports of the Ministry of Health in 2023, preterm births accounted for 4.5% of all births. Preterm births are considered to be the leading cause of neonatal morbidity and mortality, and a factor determining the health status of children at older ages. Therefore, preterm births belong to priority areas of modern health care. The prognosis, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of spontaneous preterm births are directly related to the reduction of preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age [1][2].

Spontaneous preterm birth is considered a syndrome rather than a certain condition and may be caused by one or more mechanisms. The multivector nature of cause-effect relationships explains the complexity of developing universal effective diagnostic and therapeutic measures to prevent preterm births [3].

Cervical shortening refers to one of the criteria for isthmic-cervical insufficiency and a proven risk factor for premature labor, developing weeks or even months before delivery. Structural changes in the cervix can be quantified by transvaginal ultrasound. Comparative studies are constantly in progression to determine the prognostic role of determining the length of the closed part of the cervix, and the uterocervical angle [4–8]. The length of the closed part of the cervix is claimed to be a determining criterion for threatened preterm births with a high negative prognostic value (97.9%) and relatively good specificity (82.5%) [4]. A uterocervical angle is being actively studied for the prognosis of preterm births [5]. A review of 5061 pregnant women showed that an increase in uterocervical angle serves as a risk marker for preterm birth in both singleton and multiple pregnancies [6]. In turn, simultaneous determination of the cervical length and uterocervical angle can improve prognosis [7][8]. Other ultrasound markers of preterm births to be studied include a smoothness index, cervical volume, combined uterocervical index, cervical vascular index, etc. [9].

Currently, micronized progesterone, cerclage, and pessary are used to correct isthmic-cervical insufficiency [10]. The efficacy of pessaries for preventing preterm births remains questionable [11]. One study questioned the efficacy of a pessary for the prevention of preterm births at cervical length ≤ 25 mm and singleton pregnancies [12], while another study showed the efficacy of a cervical pessary only for preventing preterm births before 28 weeks in twin pregnancies [13]. Nevertheless, most publications reveal the significant efficacy of pessaries in isthmic-cervical insufficiency if the patient population is correctly selected taking into account the anamnesis, cervical parameters, and contraindications [14–19]. Treatment with a pessary can prevent spontaneous preterm births in asymptomatic women with a short cervix detected in the middle of the second trimester of pregnancy, including cases with a history of preterm births, assisted reproductive technology pregnancies complicated by isthmic-cervical insufficiency [16][17]. A pessary fails to be effective for correcting a short cervix and preventing preterm births in case of intrauterine infection, for preventing preterm births after labor suppressed by tocolysis at 24–34 weeks of pregnancy [18][19].

The exact mechanisms of the pessary are being investigated. The mechanical support provided by the pessary is thought to contribute to cervical lengthening and sacralization [11][20]. However, specific changes in cervical parameters after inserting pessaries and the impact of these changes on the outcome of pregnancy are yet to be determined. The period after pessary insertion requires monitoring of cervical parameters for further prognosis of a preterm birth and detection of complications due to pessary insertion [21][22].

The shape, size range, and material of pessaries are being improved, thereby requiring additional studies to evaluate the characteristics of the cervix after the insertion of different types of pessaries. This will allow the mechanism of their action to be established and their effectiveness in the prevention of preterm births to be determined in each specific clinical situation.

In the context of the aforementioned, the current study aims to substantiate a differentiated approach to the selection of a pessary type for correcting isthmic-cervical insufficiency and preventing preterm births based on the evaluation of cervical parameters.

METHODS

Study design

The study followed the design of a randomized prospective trial involving 90 pregnant women diagnosed with isthmic-cervical insufficiency corrected with an obstetric pessary; cervical parameters were studied before and after correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency.

Compliance criteria

Eligibility criteria

Pregnant women at 19–24 weeks with a diagnosis of isthmic-cervical insufficiency, a cervical length of 25 mm or less, determined by transvaginal ultrasound; singleton pregnancy.

Non-inclusion criteria

Pregnant women with signs of threatened spontaneous late miscarriage; multiple pregnancies; bloody discharge from the genital tract; pregnancy resulting from assisted ART; fetal anomalies, infectious inflammatory diseases of the vagina.

Exclusion criteria

Patient’s refusal to participate in the study, refusal of dynamic follow-up; maternal and fetal conditions requiring termination of pregnancy and/or early delivery.

Research conditions

The study was carried out at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology with the course of the Faculty of Advanced Training and Retraining of Gomel State Medical University, on the basis of Gomel City Clinical Hospital No. 2 and Gomel Regional Diagnostic Medical and Genetic Center with Marriage and Family Consulting Center.

Study duration

Recruitment and result recording was carried out from January 2015 to December 2019. Patients were followed up from the time of diagnosis until the completion of pregnancy. The diagnosis of isthmic-cervical insufficiency (ICD-10 code — O34.3) was made on the basis of anamnestic data, clinical examination, and transvaginal ultrasound cervicometry.

Description of medical intervention

The selection of participants involved transvaginal ultrasound cervicometry at 19–24 weeks for diagnosis of isthmic-cervical insufficiency. Medical interventions included examination by an obstetrician-gynecologist, medical history, speculum examination, microscopic and bacteriological examination of the discharge of the genital tract to exclude infectious inflammatory diseases of the vagina, ultrasound in the second trimester of pregnancy in order to exclude multiple pregnancies and fetal anomalies. After confirming the absence of urogenital infections and normal myometrial tone, all patients underwent correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency by insertion of either an obstetric unloading pessary or a cervical perforated pessary (both pessaries were manufactured by CJSC Simurg, Republic of Belarus). The size of the pessaries was selected in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions, depending on the patient parity, the size of the upper third of the vagina, and the diameter of the cervix measured by ultrasound. Insertion of a pessary was performed in a gynecological examination chair under aseptic conditions. An obstetric unloading pessary, having the shape of a trapezoid with rounded corners, was prepositioned vertically at vaginal orifice. The pessary was inserted starting with the lower half-ring of the wide base, then the upper half-ring of the wide base, and the entire pessary was advanced deep into the vagina. The pessary was then turned in an oblique position relative to the axis of the patient’s body and placed with a wide base in the vaginal vault, a narrow base to the pubic symphysis, and the cervix in the central opening of the pessary. Before insertion, a cervical pessary, having the shape of a deep bowl, was squeezed with the fingers of the hand to reduce its size and was inserted into the woman’s vagina with a small section. The pessary was turned around so that the cervix was located in the central opening, and the convex part of the pessary was facing the vaginal vaults.

Study outcomes

Primary outcome of the study

The endpoint of the study was considered to be the completion of pregnancy by delivery both at more than 37 weeks of gestation (effective prevention of preterm birth) and before 37 weeks, when the prolonged term of pregnancy was taken into account. The efficacy of an obstetric unloading pessary and a perforated cervical pessary for the prevention of preterm births was evaluated and cervical parameters modifiable with the use of both types of pessaries for the treatment of isthmic-cervical insufficiency were determined. The frequency of the following complications after the insertion of pessaries was analyzed: displacement of the pessary, prolapse of the fetal membranes in the vagina, cervical edema, amniotic fluid sludge, increased myometrial tone.

Additional outcome of the study

Not provided by the present study.

Outcome registration methods

The efficacy of correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency in the groups was assessed as the number of deliveries at more than 37 weeks of gestation (term delivery). Cervical parameters were evaluated using ultrasound diagnostic devices equipped with a transvaginal transducer with an operating frequency of 5 MHz. Transvaginal ultrasound cervicometry determined the total length of the isthmic-cervical region in mm; the length of the closed part of the cervical region in mm; the depth of prolapse of membranes into the cervical canal in mm; the opening and shape of the internal os in mm; the value of the uterocervical angle in degrees. Cervical parameters were measured starting from days 2–3 after inserting the pessary and then in dynamics with an 4 week interval until 36 weeks of pregnancy or until the time of preterm birth and compared depending on the type of a pessary.

Randomization

Two groups were formed randomly. Sampling of patients was performed by a sequential method as they sought medical help. The first group (OUP group) had obstetric unloading pessaries inserted, while the second group (PCP group) — perforated cervical pessaries.

Data anonymization

The authors of the study performed anonymization when obtaining and further processing the primary data of the patients. A new key code was introduced for the parameters of patients in the case of the study, without announcing the binding of the code to personal data.

Statistical procedures

Principles of sample size calculation

The sample size was not pre-calculated.

Statistical methods

RESULTS

Sampling (grouping) of patients

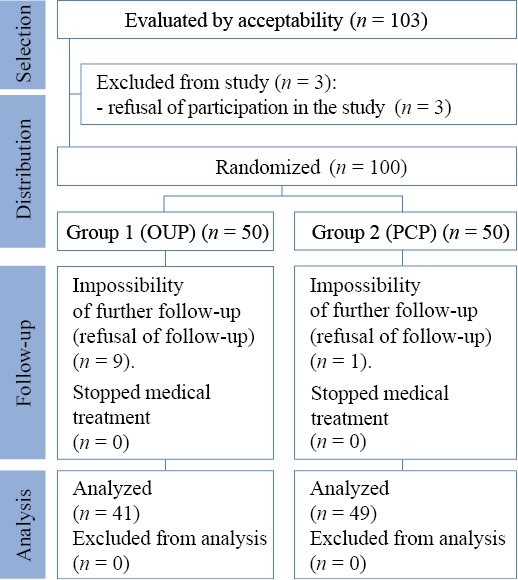

The sample was formed in accordance with the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The study enrolled 100 patients with isthmic-cervical insufficiency. Of these, 50 patients had obstetric unloading pessaries inserted and 50 patients — perforated cervical pessaries. 9 patients with obstetric unloading pessaries and 1 patient with a perforated cervical pessary further refused from dynamic transvaginal ultrasound cervicometry. Therefore, the final analysis of the study results was carried out in 90 pregnant women. As a result, 41 pregnant women were included in the obstetric unloading pessary group, and 49 pregnant women were included in the perforated cervical pessary group. The schematic diagram of the research design is shown in Figure 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic diagram of the research design

Note: performed by the authors (according to CONSORT recommendations). Abbreviations: OUP — obstetric unloading pessary; PCP — perforated cervical pessary.

Рис. 1. Блок-схема дизайна исследования

Примечание: блок-схема выполнена авторами (согласно рекомендациям CONSORT). Сокращения: OUP — акушерский разгружающий пессарий; PCP — цервикальный перфорированный пессарий.

Characteristics of the study sample (groups)

The age of the women in the obstetric unloading pessary (OUP) group accounted for 27 (26; 32) years and was not statistically significantly different from women in the perforated cervical pessary (PCP) group — 28.5 (26; 31) years (U = 811; p = 0.98). The gestational period of correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency in the OUP group amounted to 167 (154; 173) days, which had no statistically significant differences with the PCP group — 166 (156; 173) days (U = 941; p = 0.61). The groups did not differ in pregnancy and delivery parity: the proportion of multigravidas accounted for 75.6% (31 of 41 women) in the OUP group and 81.6% (40 of 49 women) in the PCP group (χ² = 0.192; p = 0.661). The proportion of multiparas in the OUP group comprised 46.3% (19 of 41) and in the PCP group — 34.7% (17 of 49) (χ² = 0.823; p = 0.364). A history of miscarriage was observed in 36.6% of patients (15 of 41) in the OUP group and 26.5% of women (13 of 49) in the PCP group, which was comparable (χ² = 0.636; p = 0.425).

Main findings of the study

The gestational period for the verification of isthmic-cervical insufficiency in pregnant women of the OUP group amounted to 159 (147; 165) days and did not differ from the PCP group — 160 (154; 164) days (U = 872; p = 0.5). A comparative analysis of cervical parameters was carried out based on the transvaginal ultrasound data at the initial diagnosis of isthmic-cervical insufficiency. The length of the closed part of the cervical region in all patients was less than 25 mm, while the total cervical length including the infundibulum (total length of the cervical region) was significantly greater, up to 40 mm, which was often interpreted as normal cervical length, and the risk of preterm births was underestimated at the preliminary stage. The ultrasound parameters of the cervix before correcting the isthmic-cervical insufficiency by different types of pessaries were comparable in both groups (Table 1).

Table 1. Cervical parameters before correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency in comparison groups, Me (25; 75)

Таблица 1. Параметры шейки матки до коррекции истмико-цервикальной недостаточности в группах сравнения, Ме (25; 75)

|

Parameters |

Group 1 (OUP) (n = 41) |

Group 2 (PCP) (n = 49) |

Statistical parameters: U, p |

|

TLCR, mm |

29 (23; 36) |

26 (23; 34) |

U = 978; р = 0.83 |

|

LCPCR, mm |

23 (20; 23) |

23 (21; 24) |

U = 923; р = 0.51 |

|

DPM, mm |

7 (0; 15) |

7 (0; 12) |

U = 959; р = 0.51 |

|

IO, mm |

7 (0; 12) |

6 (0; 10) |

U = 952; р = 0.51 |

|

UCA,° |

115 (110; 130) |

110 (100; 130) |

U = 872; р = 0.28 |

Note: compiled by the authors. Abbreviations: OUP — obstetric unloading pessary; PCP — perforated cervical pessary; TLCR — total length of the cervical region; LCPCR — length of the closed part of the cervical region; DPM — depth of prolapse of membranes; IO — internal os; UCA — uterocervical angle.

Примечание: таблица составлена авторами; Сокращения: OUP — акушерский разгружающий пессарий; PCP — цервикальный перфорированный пессарий; TLCR — общая длина цервикального отдела; LCPCR — длина сомкнутой части цервикального отдела; DPM — глубина пролабирования плодных оболочек; IO — внутренний зев; UCA — утеро-цервикальный угол.

On days 2–3 after inserting pessaries, no complaints were reported when interviewing patients of both groups. The cervical parameters were re-examined. The reported changes in some cervical parameters against the background of pessary insertion depended on the type of the pessary used (Table 2).

Table 2. Cervical parameters in transvaginal ultrasound before correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency and on days 2–3 after correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency using obstetric unloading pessaries and perforated cervical pessaries, Me (25; 75)

Таблица 2. Параметры шейки матки при проведении трансвагинального ультразвукового исследования до коррекции истмико-цервикальной недостаточности и на 2–3-й день после коррекции истмико-цервикальной недостаточности при помощи акушерского разгружающего пессария и цервикального перфорированного пессария, Ме (25; 75)

|

Indicator |

Group 1 (OUP) (n = 41) |

Group 2 (PCP) (n = 49) |

||

|

before |

after |

before |

after |

|

|

TLCR, mm |

29 (23; 36) |

30 (32; 35) |

26 (23; 34) |

29 (25; 33) |

|

LCPCR, mm |

23 (20; 23) |

22 (19; 25) |

23 (21; 24) |

25 (21; 27)* |

|

DPM, mm |

7 (0; 15) |

5 (0; 12) |

7 (0; 12) |

0 (0; 10) |

|

IO, mm |

7 (0; 12) |

5 (0; 12) |

6 (0; 10) |

0 (0; 12) |

|

UCA,° |

115 (110; 130) |

100 (90; 115)* |

110 (100; 130) |

110 (105; 125) |

|

Statistical parameters: Z, p |

ZUCA = 2.3; p = 0.021 |

ZLCPCR = 2.6; p = 0.009 |

||

Note: the table was compiled by the authors; * p < 0.05 for z value from the Wilcoxon test. Abbreviations: OUP — obstetric unloading pessary; PCP — perforated cervical pessary; TLCR — total length of the cervical region; LCPCR — length of the closed part of the cervical region; DPM — depth of prolapse of membranes; IO — internal os; UCA — uterocervical angle.

Примечание: таблица составлена авторами; * p < 0,05 для Z-критерия Вилкоксона. Сокращения: OUP — акушерский разгружающий пессарий; PCP — цервикальный перфорированный пессарий; TLCR — общая длина цервикального отдела; LCPCR — длина сомкнутой части цервикального отдела; DPM — глубина пролабирования плодных оболочек; IO — внутренний зев; UCA — утеро-цервикальный угол.

Inserting obstetric unloading pessaries led to a significant decrease in uterocervical angle from 115 (110; 130)° to 100 (90; 115)° (Z = 2.3; p = 0.021), which resulted in redistribution of pressure exerted by the fetus and extrafetal structures from the cervix to the anterior lower uterine segment. Thus, the effect of cervical unloading was realized while maintaining its original length. No closure of the internal os and no decrease in prolapse of the membranes into the cervical canal were reported. In turn, correcting the isthmic-cervical insufficiency using perforated cervical pessaries led to a significant increase in the length of the closed part of the cervix from 23 (21; 24) mm to 25 (21; 27) mm (Z = 2.6; p = 0.009), and revealed a tendency to reduce the depth of prolapse of the fetal membranes into the cervical canal (Z = 1.9; p = 0.06). Thus, the effect of cervical closure was realized.

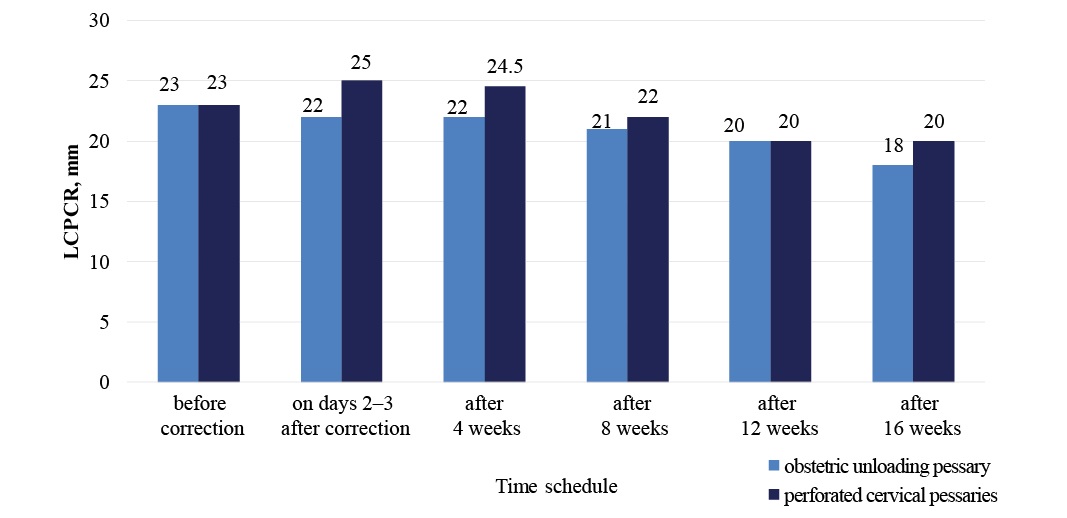

Further dynamic study was instrumental in assessing the long-term changes observed against the background of pessary insertion. The dynamics of the length of the closed part of the cervical region after correcting the isthmic-cervical insufficiency using obstetric unloading pessaries and perforated cervical pessaries is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Dynamics of change in the length of the closed part of the cervix (mm) in the correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency using different types of pessaries

Note: performed by the authors. Abbreviation: LCPCR — length of the closed part of the cervical region

Рис. 2. Динамика изменения длины сомкнутой части шейки матки (мм) при коррекции истмико-цервикальной недостаточности разными типами пессариев

Примечание: рисунок выполнен авторами. Сокращение: LCPCR — длина сомкнутой части цервикального отдела.

After inserting obstetric unloading pessaries, a gradual significant decrease in the length of the closed part of the cervix from 23 to 18 mm was noted starting from days 2–3 and further for 16 weeks, (Zafter 4–8 weeks = 4.2; p = 0.0002; Zafter 8–12 weeks = 3.9; p = 0.0009; Zafter 12–16 weeks = 2.1; p = 0.046). The observed increase in the length of the closed part of the cervix after inserting perforated cervical pessaries was noted only in the first 4 weeks, followed by a gradual significant decrease in the LCPCR during 12 weeks (Zafter 4–8 weeks from inserting PCP = 3.8; p = 0.0002; Zafter 8–12 weeks = 5.2; p < 0.0001), thereby indicating the short-term closure when using the perforated cervical pessaries. For both groups of pregnant women, irrespective of the type of pessary used, it was found that women with preterm birth, compared with women who gave birth at term, revealed a significant decrease in LCPCR between 28 and 32 weeks of pregnancy (8 and 12 weeks after correction), it accounted for 4 (2; 10) mm against 2 (0; 3) mm (U = 356; p = 0.0001). The threshold value of the decrease in the LCPCR for predicting preterm births was identified for both groups. Thus, a decrease in LCPCR of more than 4 mm in a sequential study at weeks 28 and 32 in women with corrected isthmic-cervical insufficiency was considered a significant risk factor for preterm births (AUC = 0.748; Se = 50.0%; Sp = 91.1%; 95% CI (=) 0.628–0.845; p = 0.0042).

The dynamics of changes in the uterocervical angle in the correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency using different types of pessaries is presented in Figure 3.

Fig. 3. Dynamics of changes in the uterocervical angle (°) in the correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency using different types of pessaries

Note: performed by the authors. Abbreviation: UCA — uterocervical angle

Рис. 3. Динамика изменения утеро-цервикального угла (°) при коррекции истмико-цервикальной недостаточности разными типами пессариев

Примечание: рисунок выполнен авторами. Сокращение: UCA — утеро-цервикальный угол.

Inserting obstetric unloading pessaries showed a long-term effect on the uterocervical angle. A significant decrease in the uterocervical angle, observed as early as 2–3 days after correction, persisted after 12–16 weeks (Zafter 12 weeks from inserting OUP = 2.3; p = 0.021, Zafter 16 weeks = 2.2; p = 0.046). In turn, correcting isthmic-cervical insufficiency using perforated cervical pessary led to no change in UCA on days 2–3 after inserting the pessary; moreover, it caused a significant increase in UCA from 110 (105; 125)° to 116 (110; 130)° (Z = 3.1; p = 0.003) at 28 weeks (8 weeks after the correction). A threshold value of UCA at 28 weeks of gestation equal to or greater than 112° was established for both groups, at which preterm births can be predicted with a sensitivity of 62.5% and a specificity of 71.4% (AUC = 0.733; 95% CI 0.628–0.822; p = 0.0001).

Dynamic transvaginal ultrasound timely identified the correct location of the pessary and a number of complications that arose after inserting different types of pessaries (Table 3).

Table 3. Frequency and nature of complications after correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency with different types of pessaries according to transvaginal ultrasound

Таблица 3. Частота и характер осложнений после коррекции истмико-цервикальной недостаточности разными типами пессариев по данным трансвагинального улитразвукового исследования

|

TVUS sign |

Group 1 (OUP) (n = 41) |

Group 2 (PCP) (n = 49) |

Statistical significance level, р |

||

|

abs. |

rel. |

abs. |

rel. |

||

|

Pessary displacement |

8 |

19.5% |

5 |

10.2% |

χ² = 1.56; р = 0.24 |

|

Cervical edema |

0 |

0 |

5 |

10.2% |

2p (F) = 0.06 |

|

Prolapse of the membranes in the vagina |

1 |

2.4% |

3 |

6.1% |

2p (F) = 0.62 |

|

Amniotic fluid sludge |

5 |

12.2% |

3 |

6.1% |

2p (F) = 0.46 |

|

Increased myometrial tone |

9 |

21.9% |

10 |

20.4% |

χ² = 0.01; р = 0.98 |

Note: compiled by the authors. Abbreviations: TVUS — transvaginal ultrasound; OUP — obstetric unloading pessary; PCP — perforated cervical pessary; 2p (F) — two-tailed Fisher’s exact test

Примечание: таблица составлена авторами; Сокращения: TVUS — трансвагинальное ультразвуковое исследование; OUP — акушерский разгружающий пессарий; PCP — цервикальный перфорированный пессарий; 2p (F) — двусторонний точный критерий Фишера.

In cases of pessary displacement, only part of the anterior lip of cervix uteri and/or the anterior vaginal wall was visualized in the central opening of the pessary. Overall, pessary displacement was observed in 14.4% (13 of 90) of cases, in every fifth case of obstetric unloading pessary insertion, and in 10.2% of pregnant women with perforated cervical pessary. In 2 patients with obstetric unloading pessaries (4.9%) and 1 patient with a perforated cervical pessary (2.0%), pessary displacement was detected at up to 28 weeks of gestation, and 100% of these women had subsequent preterm births (at 229, 246 and 255 days). In 3 women (7.3%) with obstetric unloading pessaries and 4 patients (8.2%) with perforated cervical pessaries, displacement was diagnosed at 32 weeks of gestation, with 71.4% (2 patients with OUP and 4 with PCP) of cases experiencing preterm births. Another 3 pregnant women with obstetric unloading pessaries (7.3%) were diagnosed as having displacement at 36 weeks’ gestation, and all women delivered at term.

Cervical edema was observed in 5.6% (5 of 90) women, and only in cases with perforated cervical pessaries. Nevertheless, cervical edema had no impact on the outcome of pregnancy; the pessary was replaced with a larger one, and all these patients delivered at term.

Fetal membranes prolapsed beyond the external os or into the vagina in 4.4% (4 of 90) of cases, regardless of the type of pessary. In 2 cases (2.2%), the pregnancy was prolonged to the full term (in one case the patient had an obstetric unloading pessary inserted, in the second case — a perforated cervical pessary), and 4.1% (2 out of 49) of cases of correcting the isthmic-cervical insufficiency with perforated cervical pessaries experienced preterm births.

A sludge in the area of the lower pole of the fetal bladder formed in 8.9% (8 out of 90) of cases. The incidence of sludge did not correlate with the type of pessary. It was observed in 12.2% (5 of 41) of women with obstetric unloading pessaries, in 6.1% (3 of 49) of women with perforated cervical pessaries. Sludge was considered an unfavorable factor for the outcome of delivery. In 75% (6 of 8) of cases with sludge, the pregnancy was terminated prematurely.

Increased myometrial tone of the lower uterine segment against the background of pessary insertion was detected in 21.1% (19 out of 90) of women in the study groups with no dependence of incidence on the type of pessary inserted. In both groups, regardless of the type of pessary, it was found that women with preterm births, compared with women with term births, significantly more often had increased myometrial tone — 46.9% (15 out of 34) of women against 7.4% (4 out of 56) of women, respectively (χ² = 15.217; p = 0.0001). At the same time, when increased myometrial tone was observed, the risk of preterm births increased 8.1 times (OR = 8.1; 95% CI — 2.6–25.2; p = 0.0003); however, at 32 weeks’ gestation, the risk of preterm births increased 23.3 times (OR = 23.3; 95% CI — 2.7–19.7; p = 0.004), requiring additional pregnancy-preserving therapy.

The proportion of term births in patients in the obstetric unloading pessary group was 61.0% (25 out of 41 women) and had no statistically significant differences with the perforated cervical pessary group, where 64.7% (31 out of 49 women) of cases occurred during full-term pregnancy (χ² < 0.0001; p = 0.996). The gestational age at preterm births in the obstetric unloading pessary group amounted to 247 (230; 253) days, and in the perforated cervical pessary group — 245 (225; 254) days and was considered comparable (U = 139; p = 0.870). A late miscarriage at 21–22 weeks according to the type of rupture of the fetal membranes was observed in 2 cases with perforated cervical pessaries, and early preterm births before 28 weeks (less than 196 days) — in 1 case of correction with a perforated cervical pessary. Preterm births at 28–34 weeks (196–237 days) was observed in 8 (8.8%) women with pessary-corrected isthmic-cervical insufficiency, at 34–37 weeks (238–258 days) — in 23 (25.5%) women and had no significant difference depending on the type of pessary chosen.

Additional results of the study

Not obtained.

Adverse events

Not identified.

DISCUSSION

Limitations of the study

The study has limitations in the form of low statistical power due to limited number of patients.

Generalizability/extrapolation

The results of the present study may be generalizable to other types or experimental research settings. In particular, when using other types of pessaries different from those used in the study, ultrasound evaluation of cervical parameters before and after pessary insertion will contribute to evaluating their mechanisms and efficacy both for the treatment of isthmic-cervical insufficiency and for the diagnosis of complications requiring additional medical interventions.

Summary of the primary outcome of the study

The study demonstrated the high efficacy of both obstetric unloading pessary and perforated cervical pessary. The data obtained confirm the need for a differentiated approach to selecting the type of pessary for the correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency. A significant result consists in identifying the parameters of the cervix in isthmic-cervical insufficiency, which can be corrected using different types of pessaries and thus more effectively prevent preterm births.

Discussion of the primary outcome of the study

Against the background of contradictory publications on the efficacy of obstetric pessaries in correcting the isthmic-cervical insufficiency and preventing preterm births [11–14], as well as in the context of improving the shape, size, and material of pessaries, the present study showed the efficacy of obstetric unloading pessaries and perforated cervical pessaries in preventing 61 and 64.7% of potential preterm births due to isthmic-cervical insufficiency, which is consistent with the results of previous studies [16][17]. The main cause of neonatal and infant mortality in preterm births is associated with deliveries before 28 weeks [1]. According to Y.O. Xiong et al., obstetric pessaries prevent such births only in case of multiple pregnancies [13]. In our study, obstetric unloading pessaries and perforated cervical pessaries demonstrated high efficacy (100 and 97%, respectively) in preventing early preterm births in singleton pregnancies and allowed for prolongation of pregnancy for 14 weeks.

These studies recognize the importance of developing clearer criteria to justify the use of an obstetric pessary, as well as transvaginal ultrasound monitoring of cervical parameters and accurate placement of the pessary, in order to increase the efficacy of pessaries for the correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency and prevention of preterm births [2][20–22]. The need for differentiated selection of the pessary type is attributable to the difference of the parameters corrected by various pessaries. Inserting an obstetric unloading pessary induces a significant decrease in uterocervical angle (p = 0.021), and corrects the isthmic-cervical insufficiency using an obstetric unloading pessary, which leads to an increase in the length of the closed part of the cervix (p = 0.009) and a slight decline in the depth of prolapse of the fetal membranes into the cervical canal (p = 0.06). The correction mechanism of an obstetric unloading pessary is associated with the redistribution of pressure exerted by the fetus and extrafetal structures from the cervix to the anterior lower uterine segment, while the corrective action of a perforated cervical pessary is based on the closure of the cervix. The evaluation of the length of the closed part of the cervix, internal os, the depth of prolapse of membranes, and uterocervical angle using transvaginal ultrasound cervicometry in the second trimester will allow for choosing the appropriate type of pessary and maximizing the effect of its use.

Ultrasound control after correcting the isthmic-cervical insufficiency by a pessary is found to be an integral part of the further prognosis of a preterm birth [2][21]. As early as 2–3 days after pessary insertion, it is possible to assess what cervical parameters have been corrected. Further dynamic cervicometry serves to detect the progression of cervical shortening and prolapse of the fetal membranes, diagnose such complications as pessary displacement, cervical edema, amniotic fluid sludge, and increased myometrial tone, which requires timely therapeutic measures to reduce the risk of preterm births.

CONCLUSION

Ultrasound parameters of the cervix are critical in selecting a pessary type for prevention of preterm births in isthmic-cervical insufficiency. Application of an obstetric unloading pessary is aimed at reducing the uterocervical angle, and a perforated cervical pessary increases the length of the closed part of the cervical region. Treatment of isthmic-cervical insufficiency using an obstetric unloading pessary and cervical pessary can prevent, respectively, 61 and 64.7% of potential preterm births, including 100% and 97% of early births before 28 weeks of gestation. Dynamic ultrasound monitoring with determination of cervical parameters after pessary insertion enables complications to be timely assessed and corrected, thereby increasing the efficacy of obstetric pessaries for the correction of isthmic-cervical insufficiency and prevention of preterm births.

References

1. Walani SR. Global burden of preterm birth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2020;150(1):31–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13195

2. Kaplan YuD, Zakharenkova TN. Prediction of Spontaneous Preterm Birth in Women with Ischemic-Cervical Insufficiency Corrected with the Pessary. Health and Ecology Issues. 2019;4:43–48 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.51523/2708-6011.2019-16-4-8

3. Vidal MS Jr, Lintao RCV, Severino MEL, Tantengco OAG, Menon R. Spontaneous preterm birth: Involvement of multiple feto-maternal tissues and organ systems, differing mechanisms, and pathways. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:1015622. https://doi.org/10.3389/fendo.2022.1015622

4. Thain S, Yeo GSH, Kwek K, Chern B, Tan KH. Spontaneous preterm birth and cervical length in a pregnant Asian population. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0230125. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230125

5. Sawaddisan R, Kor-Anantakul O, Pruksanusak N, Geater A. Distribution of uterocervical angles in the second trimester of pregnant women at low risk for preterm delivery. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021;41(1):77–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443615.2020.1718622

6. Hessami K, Kasraeian M, Sepúlveda-Martínez Á, Parra-Cordero MC, Vafaei H, Asadi N, Benito Vielba M. The Novel Ultrasonographic Marker of Uterocervical Angle for Prediction of Spontaneous Preterm Birth in Singleton and Twin Pregnancies: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2021:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1159/000510648

7. Luechathananon S, Songthamwat M, Chaiyarach S. Uterocervical Angle and Cervical Length as a Tool to Predict Preterm Birth in Threatened Preterm Labor. Int J Womens Health. 2021;13:153–159. https://doi.org/10.2147/IJWH.S283132

8. Singh PK, Srivastava R, Kumar I, Rai S, Pandey S, Shukla RC, Verma A. Evaluation of Uterocervical Angle and Cervical Length as Predictors of Spontaneous Preterm Birth. Indian J Radiol Imaging. 2022;32(1):10–15. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1741411

9. Tanacan A, Sakcak B, Denizli R, Agaoglu Z, Farisogullari N, Kara O, Sahin D. The utility of combined utero-cervical ındex in predicting preterm delivery in pregnant women with preterm uterine contractions. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2024;310(1):377–385. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-024-07395-4

10. Dobrokhotova YuE, Borovkova EI, Zalesskaya SA, Nagaitseva EA, Raba DP. Diagnosis and management patients with cervical insufficiency. Gynecology 2018;20(2):41–45 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.26442/2079-5696_2018.2.41-45

11. Marochko KV, Parfenova YaA, Artymuk NV, Novikova ON, Beglov DE. Use of pessary for cervical insufficiency: a discussion. Fundamental and Clinical Medicine. 2023;8(1):109–118 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.23946/2500-0764-2023-8-1-109-118

12. Saccone G, Ciardulli A, Xodo S, Dugoff L, Ludmir J, Pagani G, Visentin S, Gizzo S, Volpe N, Maruotti GM, Rizzo G, Martinelli P, Berghella V. Cervical Pessary for Preventing Preterm Birth in Singleton Pregnancies With Short Cervical Length: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Ultrasound Med. 2017;36(8):1535–1543. https://doi.org/10.7863/ultra.16.08054

13. Xiong YQ, Tan J, Liu YM, Qi YN, He Q, Li L, Zou K, Sun X. Cervical pessary for preventing preterm birth in singletons and twin pregnancies: an update systematic review and meta-analysis. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2022;35(1):100–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1712705

14. Goya M, Pratcorona L, Merced C, Rodó C, Valle L, Romero A, Juan M, Rodríguez A, Muñoz B, Santacruz B, Bello-Muñoz JC, Llurba E, Higueras T, Cabero L, Carreras E; Pesario Cervical para Evitar Prematuridad (PECEP) Trial Group. Cervical pessary in pregnant women with a short cervix (PECEP): an open-label randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9828):1800–1806. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60030-0

15. Goya M, de la Calle M, Pratcorona L, Merced C, Rodó C, Muñoz B, Juan M, Serrano A, Llurba E, Higueras T, Carreras E, Cabero L; PECEP-Twins Trial Group. Cervical pessary to prevent preterm birth in women with twin gestation and sonographic short cervix: a multicenter randomized controlled trial (PECEP-Twins). Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;214(2):145–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.11.012

16. Timokhina EV, Strizhakov AN, Pesegova SV, Belousova VS, Samoilova YuA. The choice of techniques for correction of isthmic-cervical insufficience: the results of the retrospective study. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2021;8:86–93 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.185565/aig.2021.8.86-92

17. Issenova SSh, Nurgalym AE, Saduakasova ShM, Boran AM, Nurlanova GK. Cervical insufficiency in pregnant women after ivf: a retrospective research. Reproductive medicine. 2023;1(54):29–34 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.37800/RM.1.2023.29-34

18. Zakharenkova TN, Kruglikova AV, Voronkova EA. Correction of cervical insufficiency during prolapse of the fetal bladder and intrauterine infection. Health and Ecology Issues. 2023;20(2):128–134. https://doi.org/10.51523/2708-6011.2023-20-2-16

19. Mastantuoni E, Saccone G, Gragnano E, Di Spiezio Sardo A, Zullo F, Locci M; Italian Preterm Birth Prevention Working Group. Cervical pessary in singleton gestations with arrested preterm labor: a randomized clinical trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol MFM. 2021 Mar;3(2):100307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajogmf.2021.100307

20. Grobman WA, Norman J, Jacobsson B; FIGO Working Group for Preterm Birth. FIGO good practice recommendations on the use of pessary for reducing the frequency and improving outcomes of preterm birth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2021;155(1):23–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijgo.13837

21. Schnettler W, Manoharan S, Smith K. Transvaginal Sonographic Assessment Following Cervical Pessary Placement for Preterm Birth Prevention. AJP Rep. 2022;12(1):e80–e88. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0041-1742273

22. Mendoza Cobaleda M, Ribera I, Maiz N, Goya M, Carreras E. Cervical modifications after pessary placement in singleton pregnancies with maternal short cervical length: 2D and 3D ultrasound evaluation. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2019;98(11):1442–1449. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13647

About the Authors

T. N. ZakharenkovaBelarus

Tatsiana N. Zakharenkova — Cand. Sci. (Med.), Assoc. Prof., Head of the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology with the course of the Faculty of Advanced Training and Retraining, Gomel State Medical University.

Lange str., 5, Gomel, 246000

Yu. D. Kaplan

Belarus

Yuliya D. Kaplan — Cand. Sci. (Med.), Assoc. Prof., Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology with the course of the Faculty of Advanced Training and Retraining, Gomel State Medical University.

Lange str., 5, Gomel, 246000

S. N. Zanko

Belarus

Sergey N. Zanko — Dr. Sci. (Med.), Prof., Honored Scientist of the Republic of Belarus, Chairman of the Board, Belarusian Medical Public Association “Reproductive Health”.

Frunze Ave., 81–2025, Vitebsk, 210033

T. N. Kovalevskaya

Belarus

Tatsiana N. Kovaleuskaya — Assistant, Department of Public Health and Healthcare with the course of the Faculty of Advanced Training and Retraining. Vitebsk State Order of Peoples’ Friendship Medical University.

Frunze Ave., 27, Vitebsk, 210009

Supplementary files

Review

For citations:

Zakharenkova T.N., Kaplan Yu.D., Zanko S.N., Kovalevskaya T.N. Differential use of various types of pessaries in isthmic-cervical insufficiency for prevention of preterm birth: A randomized prospective trial. Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2024;31(5):15-25. https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2024-31-5-15-25