Scroll to:

Effect of transcranial electrical stimulation on serum interleukin-1β levels in COVID-19 patients: A randomized prospective study

https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2025-32-6-41-55

Abstract

Background. Interleukin-1β plays an important role in the pathogenesis of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and may also be informative as a prognostic marker of infection. Other widely used diagnostic and prognostic markers include C-reactive protein and ferritin.

Objective. To evaluate the effect of transcranial electrical stimulation on the serum levels of interleukin-1β, C-reactive protein, and ferritin in moderate to severe COVID-19 patients who do not receive targeted anti-cytokine therapy.

Methods. The conducted randomized prospective study included patients treated at the Regional Clinical Hospital No. 2 (Ministry of Health of the Krasnodar Krai) in the period from June 24, 2021 to February 23, 2022. The patients diagnosed with moderate to severe COVID-19 were divided into two groups: comparison group (n = 20) receiving standard treatment as per the current guidelines and a group (n = 15) in which, in addition to standard therapy, the patients received transcranial electrical stimulation (one session per day until day 7 of stay in the COVID ward). The study excluded patients receiving specific anti-cytokine therapy (monoclonal antibodies, kinase inhibitors, and recombinant cytokine receptor antagonists). The levels of interleukin-1β, C-reactive protein, and ferritin were assessed prior to treatment and at the end of the first week of therapy. Statistical analysis and data visualization were performed in the R environment (The R Foundation, Austria). Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

Results. Prior to treatment, no statistically significant differences were observed in the levels of interleukin-1β, C-reactive protein, and ferritin between the groups. By the end of the first week, the level of interleukin-1β decreased by 11.8% (p = 0.7) in the comparison group, which was not statistically significant. In the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation, interleukin-1β levels exhibited a significant decrease (by 71%) from the baseline (p = 0.007). In addition, interleukin-1β levels in this group were 52% lower than in the comparison group (p = 0.005). Also, C-reactive protein levels decreased significantly in both groups, while ferritin levels did not exhibit any statistically significant changes.

Conclusion. The use of transcranial electrical stimulation in combination therapy for moderate to severe COVID-19 patients results in a more pronounced decrease in serum interleukin-1β levels as compared to standard therapy, which may indicate the anti-inflammatory potential of this method.

Keywords

For citations:

Ignatenko M.Yu., Kochkarova E.V., Izmaylova N.V., Zanin S.A. Effect of transcranial electrical stimulation on serum interleukin-1β levels in COVID-19 patients: A randomized prospective study. Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2025;32(6):41-55. https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2025-32-6-41-55

INTRODUCTION

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) constitutes a serious challenge for modern medicine and healthcare [1][2]. Its pathogenesis and fatal complications are associated with systemic immune dysregulation, including an abnormal secretion profile of various cytokines. Among them, a central role is played by interleukin (IL)-1β. Hyperproduction of proinflammatory substances underlies the pathogenesis of severe, life-threatening disease manifestations: cytokine release syndrome, thrombosis, and secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (macrophage activation syndrome), which can ultimately lead to multiple organ failure [1–3]. In spite of the progress made in targeted anti-cytokine therapy, it is necessary to continue the search for treatment methods that can address immune dysregulation and other components of COVID-19 pathogenesis.

Attention of clinicians around the world is drawn to methods of non-invasive electrical brain stimulation. These methods can be classified as transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS), transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS), and transcranial pulsed current stimulation (tPCS) [4]. The transcranial electrical stimulation (TES therapy) developed under the supervision of Valery Lebedev combines pulsed- and direct-current stimulation, even though in foreign literature it is often referred to as tPCS; the term “Lebedev’s currents” is also used [4][5]. Although transcranial electrical stimulation is being extensively studied in various contexts by domestic and foreign scientists [5–8], no studies on its effects in COVID-19 are currently available. The same cannot be said about other methods of non-invasive electrical stimulation of the nervous system. For example, Pinto et al. (2023) studied the effects of a single tDCS session (current magnitude of up to 2 mA) in 20 patients aged between 18 and 80 years who had been hospitalized with acute SARS-CoV-2 infection but without extremely severe symptoms. The authors showed that the procedure is safe and has no serious side effects (i.e., those related to the infection, as well as other side effects); they also revealed a number of positive effects of the procedure. As compared to 20 patients in the control group, the tDCS group exhibited normalization of heart rate variability (which the researchers attribute to the modulation of cardiac autonomic regulation) and increased oxygen saturation [9]. Noteworthy is that these phenomena were observed after a single session of the procedure. Another study conducted by Andrade et al. (2022) involved 56 intensive care patients, including 28 patients who received tDCS (up to 3 mA) two times per day for 10 days. No difference in side effects was observed between the stimulation and control groups. In the tDCS group, a higher number of ventilator-free days were reported (primary endpoint), and the patients showed more pronounced positive changes in organ failure indicators (Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score) [10]. A large number of studies consider the use of electrical stimulation methods to address the long-term effects of infection, including long COVID [11]. At the stage of rehabilitation, the stress-limiting, anxiolytic, and antinociceptive effects of these methods are of particular importance. Some of these studies also focus on TES therapy [12].

The positive effects of non-invasive electrical stimulation on the nervous system can be explained as follows. First, it modulates the activity of brain centers involved, among other things, in regulating respiration, hemodynamics, and immunity [13]. For example, the parasympathetic nervous system is known to inhibit excessive immune responses; conversely, sympathoadrenal hyperactivation (characteristic of many critical conditions) adversely affects the cardiovascular system, blood rheology (promoting thrombosis), metabolism, and thermoregulation, as well as potentiating endothelial dysfunction, inflammation, etc. [13]. It has been discussed that a sympathetic (adrenergic) storm plays an important role in the development of neurogenic pulmonary edema and respiratory failure, similarly to what happens under other critical conditions [14][15]. The combination of stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy and COVID-19 may also be attributed to hypersympathicotonia and hypercatecholaminemia, as well as other mechanisms [16].

TES therapy, which has demonstrated its positive effects in various nosologies, involves the stimulation of antinociceptive brain areas (endorphinergic, serotonergic, and dopaminergic), which perform a variety of functions beyond pain suppression, including immunomodulation and stress response inhibition [7][17][18]. For example, TES therapy was shown to reduce the blood levels of a number of proinflammatory substances, such as IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF), IL-6, and IL-2 [18][19]. Similar effects were described both in laboratory animals with the use of models of various pathologies and in the clinical context in patients with inflammatory diseases of microbial and non-microbial etiology [18–20].

Drawing on these data, we can formulate the hypothesis that TES therapy may provide an additional sanogenic effect in the combination treatment of COVID-19 by suppressing the hyperproduction of proinflammatory cytokines. In addition, it is informative to evaluate laboratory indicators of acute phase response — C-reactive protein (CRP) and ferritin [21][22]. Also, a ferritin level indicates the severity of cytolysis and imbalance in the systemic iron response [22]. Thus, the present authors find it reasonable to study the effect of TES therapy on these indicators for an integrative assessment of the applicability of this method in the combination pathogenetic treatment of the considered disease.

The study aims to evaluate the effect of transcranial electrical stimulation on the serum levels of IL-1β, CRP, and ferritin in moderate to severe COVID-19 patients not receiving targeted anti-cytokine therapy.

METHODS

Study design

The conducted randomized prospective study included 35 patients with moderate to severe COVID-19; these patients were treated at Ward No. 3 for adult COVID-19 patients who do not require mechanical ventilation (Regional Clinical Hospital No. 2, Ministry of Health of Krasnodar Krai).

Eligibility criteria

Inclusion criteria

Moderate to severe course of the disease as per “Interim Guidelines: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)” of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation, which were effective during the patient’s hospital stay (versions 11–151); positive response to standard therapy in the first two days of treatment in terms of clinical and laboratory indicators (for this reason, patients were not prescribed additional anti-cytokine therapy); age of patients from 18 to 70 years; informed voluntary consent from the participants.

Exclusion criteria

Present or suspected bacterial co-infection; presence of decompensated chronic diseases; presence of contraindications to TES therapy.

Removal criteria

Discontinuation of TES therapy at the patient’s request; the need to add any specific anti-cytokine therapy to the treatment; present or suspected secondary bacterial co-infection.

Study conditions

The study was conducted at the Regional Clinical Hospital No. 2 (Ministry of Health of Krasnodar Krai) and at the Department of General and Clinical Pathophysiology of the Kuban State Medical University (Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation).

Duration of the study

The study lasted nine months (June 2021–February 2022). The patients were observed during the first seven days of their hospital stay.

Description of the medical procedure

The COVID-19 diagnosis was verified using nucleic acid amplification to identify SARS-CoV-2 virus RNA. The severity of the disease was determined in accordance with the interim guidelines of the Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation (versions 11–152).

According to the specified guidelines, the standard treatment included the starting maximum dose of glucocorticoid drugs (20 mg of dexamethasone per day), followed by a 20–25% reduction in the administration/day dose during the first two days and then by a 50% reduction every 1–2 days until discontinuation3. The patients also received anticoagulants (low molecular weight heparins): enoxaparin sodium at a dose of 40 anti-Xa IU administered subcutaneously once daily, as well as dalteparin sodium or nadroparin calcium in equivalent doses (depending on availability); the patients with a body mass index of over 30 kg/m² received 80 anti-Xa IU of enoxaparin.

Transcranial electrical stimulation was performed in the supine position using rectangular pulse current. The stimulation parameters were as follows: a pulse duration of 3.75 ± 0.25 ms, a current of 3 mA, and a frequency of 77 Hz. The electrodes were placed on the forehead and in the mastoid region. The first session, which was aimed at helping the patients adapt to the procedure, lasted 15 minutes. Subsequent procedures were carried out for 45 minutes daily for six days (one session per day).

Study outcomes

Main study outcome

The serum levels of IL-1β, CRP, and ferritin at two time points: on the day of admission to the COVID ward and at the end of the first week of treatment.

Additional study outcomes

No additional outcomes are intended.

Methods for recording outcomes

Biological material (venous blood) was collected upon admission to the COVID ward and at day 7 of hospitalization.

The serum was obtained through the centrifugation of venous blood for ten minutes at 3000 rpm.

Determination of laboratory parameters

Serum IL-1β levels were determined by means of an Interleukin-1 beta-EIA-BEST kit (A-8766; Vector-Best, Russia) as per the manufacturer’s instructions using the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay: measurement unit — pg/mL; analytical sensitivity — <1 pg/mL.

The levels of CRP were measured via turbidimetry using an Architect c8000 analyzer (Abbott, USA) and a CRP Vario kit (Abbott Laboratories, USA): measurement unit — mg/L; analytical sensitivity — 0.2 mg/L; measurement range — 0.2–320 mg/L.

Ferritin levels were measured via chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay using an Architect i2000 analyzer (Abbott, USA) and an ARCHITECT Ferritin 7K59 kit (Abbott Laboratories, USA) as per the manufacturer’s recommendations: measurement unit — ng/mL; analytical sensitivity — < 1 ng/mL.

Analyzed clinical history characteristics

The following additional variables were taken into account: presence of comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity with a body mass index of ≥30 kg/m²); features of concomitant therapy (use of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE inhibitors), angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARBs), statins, and metformin).

Tolerability assessment of transcranial electrical stimulation

Individual patient responses to the TES procedure (subjective discomfort, sleep disturbances, headache, etc.) were also recorded, followed by a qualitative tolerability assessment of the method.

Randomization

Fifty-seven patients meeting the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. The personal data of these patients (age, sex, medical history, information about comorbidities, etc.) were entered into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets (Microsoft, USA). Each participant was assigned a unique, anonymous identification number.

Randomization was performed using the Microsoft Excel random number generator (=RAND() function), which ensured an equal distribution of participants across two groups: the TES therapy group (n = 28) receiving transcranial electrical stimulation in addition to the standard treatment; the comparison group (n = 29) receiving only the standard treatment.

In the study, the clinical condition of the patients and the course of COVID-19 were monitored daily. In cases where the condition worsened, a bacterial co-infection developed, or specific anti-cytokine therapy was needed, the patient was removed from the study.

The final statistical analysis included data on 35 patients: 15 patients from the TES therapy group and 20 from the comparison group.

Data anonymity assurance

The collection and subsequent processing of patient data were conducted anonymously. The division of patients into groups and the analysis of results were carried out by the authors without the involvement of third parties.

Statistical analysis

Principles behind sample size determination

The sample size was not determined in advance, as this pilot (exploratory) study was aimed at analyzing trends in IL-1β, CRP, and ferritin levels associated with the administration of transcranial electrical stimulation in COVID-19 patients. The obtained results were intended to serve as a basis for designing subsequent studies with a priori sample power determination and calculation of the required number of participants.

Methods of statistical data analysis

Data analysis and visualization were performed in the R environment4 [23]. The normality of quantitative data distribution was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Since most parameters did not follow a normal distribution, the descriptive statistic is presented as Me (Q1; Q3) — medians and quartiles.

The intergroup comparison of quantitative indicators (TES group vs. comparison group) was performed using the Mann-Whitney U test. The effect size of intergroup differences was expressed in terms of probability of superiority (PS) using the rcompanion software5 [24].

The PS values are interpreted as follows:

- PS = 0.5 — no differences (equivalence of groups);

- PS → 0 or PS → 1 — maximum effect size (the probability that the value of the indicator in one group is higher than in another tends to 0 or 100%).

Intragroup trends (before and after treatment) were assessed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test with Pratt correction and the Coin software [25].

For dependent samples, the effect size was expressed in terms of the matched-pairs rank biserial correlation coefficient (rc) calculated using the rcompanion software.

The rc values are interpreted as follows [26][27]:

- |rc| < 0.1 — negligible effect;

- 0.1 ≤ |rc| < 0.3 — small effect,

- 0.3 ≤ |rc| < 0.5 — medium effect,

- |rc| ≥ 0.5 — large effect.

Differences were considered statistically significant at p < 0.05.

RESULTS

Study participants

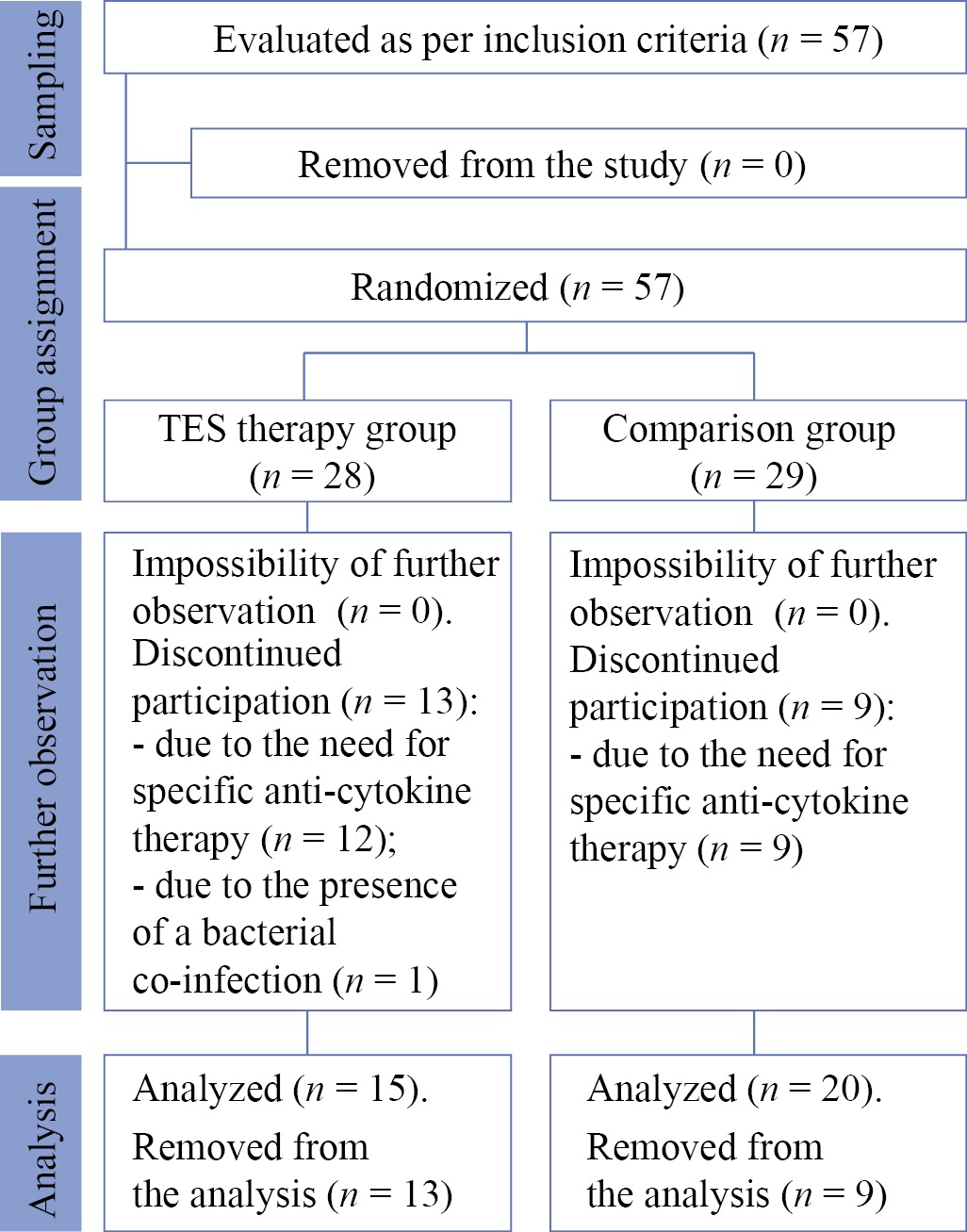

Between June 24, 2021 and February 23, 2022, 57 patients were invited to participate in the study. They were randomly divided into two study groups: the TES therapy group (n = 28) receiving transcranial electrical stimulation in addition to the standard treatment and the comparison group (n = 29) receiving the standard treatment. As a result of daily monitoring, thirteen people from the TES therapy group were removed from the study (of these, twelve patients required anti-cytokine therapy, and one was removed due to the presence of a bacterial co-infection), as well as nine people from the comparison group (due to the need for anti-cytokine therapy). Thus, the final analysis of the data was performed for 15 patients in the TES therapy group and 20 patients in the comparison group (see block diagram of the study design, Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Block diagram of the study design

Note: The block diagram was created by the authors (as per CONSORT recommendations). Abbreviation: TES — transcranial electrical stimulation.

Рис. 1. Блок-схема дизайна исследования

Примечание: блок-схема выполнена авторами (согласно рекомендациям CONSORT). Сокращение: TES — транскраниальная электростимуляция.

All the patients had moderate disease severity upon admission, except for two patients from the comparison group. Upon admission, the severity of disease in these patients was assessed as severe based on oxygen saturation (92 and 90%). After the first day of treatment, oxygen saturation consistently exceeded 93%, which was consistent with moderate severity (Table).

Table. Demographic, anthropometric, and clinical history characteristics of patients in the study groups

Таблица. Демографические, антропометрические и клинико-анамнестические показатели пациентов исследуемых групп

|

Parameter |

Comparison Group (n = 20) |

TES Therapy Group (n = 15) |

Statistical significance level of differences¹, р |

|

Age, years; Me (Q1; Q3) |

41.5 (34.7; 54.5) |

48 (36.0; 55.5) |

0.10 (MWU) |

|

Sex, abs. (%) |

|||

|

Women |

11 (55) |

6 (40) |

0.38 (FET) |

|

Men |

9 (45) |

9 (60) |

|

|

Severity upon admission, abs. (%) |

|||

|

Moderate |

18 (90) |

15 (100) |

0.21 (FET) |

|

Severe |

2 (10) |

– |

|

|

Treatment of the underlying disease |

|||

|

Glucocorticoids, abs. (%) |

19 (95) |

14 (93.3) |

0.83 (FET) |

|

Anticoagulants, abs. (%) |

20 (100) |

15 (100) |

– |

|

Comorbid nosologies |

|||

|

Diabetes mellitus, abs. (%) |

2 (10) |

0 (0) |

0.21 (FET) |

|

Body mass index exceeding 30 kg/m², abs. (%) |

1 (5) |

1 (6.7) |

0.83 (FET) |

|

Hypertension, abs. (%) |

6 (30) |

2 (13.3) |

0.25 (FET) |

|

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, abs. (%) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

– |

|

Treatment of concomitant diseases |

|||

|

ACE inhibitors or ARBs, abs. (%) |

0 (0) |

1 (6.7) |

0.24 (FET) |

|

statins, abs. (%) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

– |

|

metformin, abs. (%) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

– |

|

Baseline for the analyzed laboratory blood parameters |

|||

|

IL-1β, pg/mL; Me (Q1; Q3) |

1.7 (1.1; 2.9) |

2.4 (1.0; 3.7) |

0.70 (MWU) |

|

C-reactive protein, mg/L; Me (Q1; Q3) |

55.2 (17.9; 67.6) |

46.1 (26.7; 85.5) |

0.90 (MWU) |

|

Ferritin, ng/mL; Me (Q1; Q3) |

316.0 (212.3; 433.0) |

349.8 (156.4; 567.9) |

0.80 (MWU) |

Note: The table was compiled by the authors. ¹MWU — Mann-Whitney U test, FET — Fisher’s exact test. Abbreviations: ARBs — angiotensin II receptor blockers; ACE inhibitors — angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; TES — transcranial electrical stimulation.

Примечание: таблица составлена авторами. ¹MWU — критерии Манна — Уитни, FET — точный критерий Фишера. Сокращения: ARBs — антагонисты рецепторов к ангиотензину II, ACE — ингибиторы ангиотензинпревращающего фермента, TES — транскраниальная электростимуляция.

Thus, the two study groups were comparable in terms of the main analyzed indicator in addition to their comparability in terms of the severity of the underlying disease, demographic characteristics, comorbidity, treatment of concomitant pathologies, and the standard treatment of the disease (according to the interim guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of COVID-19 effective at the time of hospitalization) (see Table).

Main study results

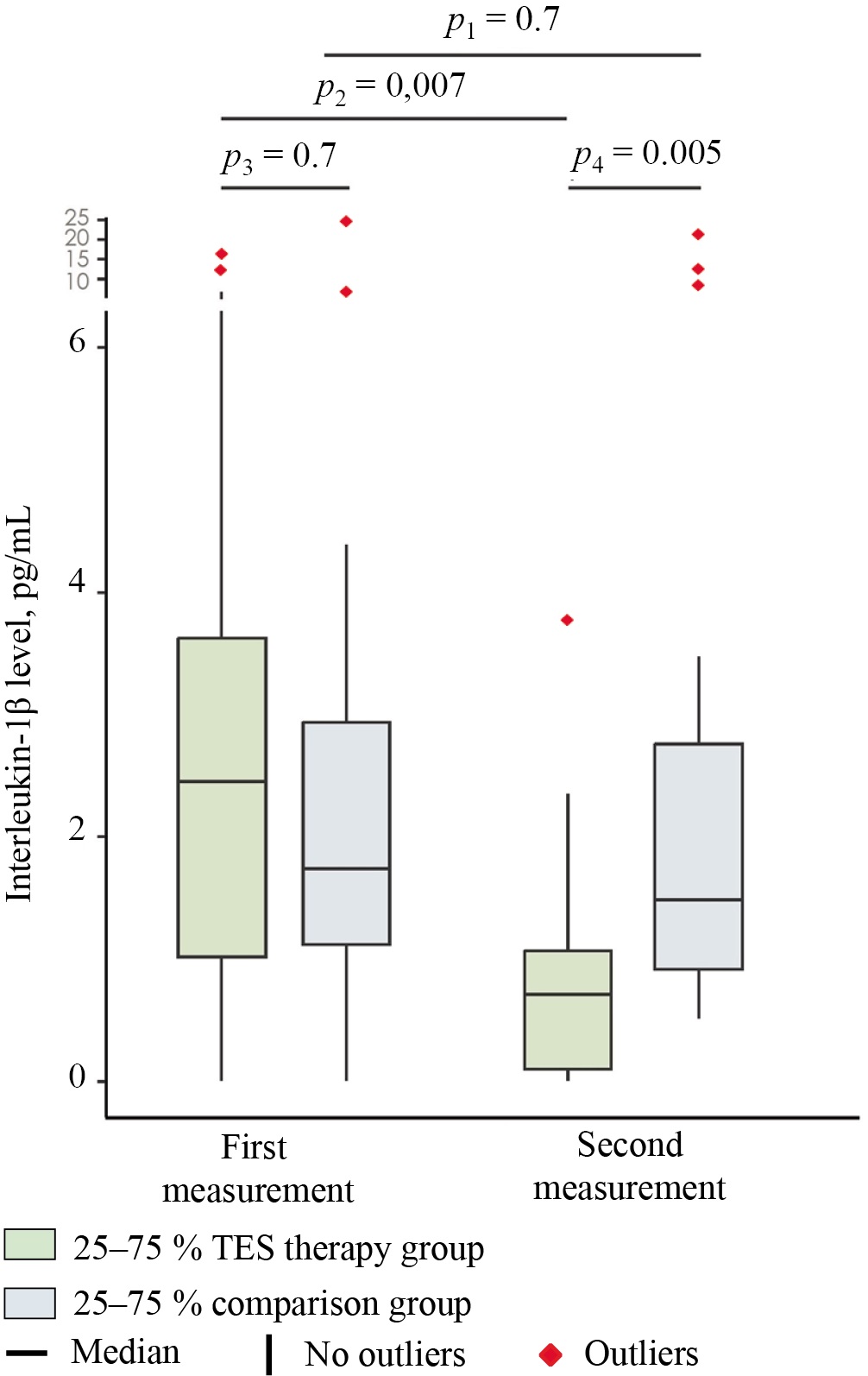

Figure 2 shows the serum IL-1β levels of the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation and the comparison group prior to treatment (first measurement). The median value of this indicator in TES therapy group (2.4 [ 1.0; 3.7] pg/mL) was 41.2% higher than in the comparison group (1.7 (1.1; 2.9) pg/mL; however, the difference between the groups was statistically insignificant (p = 0.7; effect size — PS = 0.5 [ 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.3–0.7]).

Fig. 2. Median serum levels of interleukin-1β in the study groups at days 1 (first measurement) and 7 (second measurement) of hospitalization

Note: The figure was created by the authors. Significance levels: p1 — significance level of differences between days 1 and 7 in the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation (intra-group comparison); p2 — significance level of differences between days 1 and 7 in the comparison group (intra-group comparison); p3 — significance level of differences between the comparison group and the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation before treatment (day 1); p4 — significance level of differences between the comparison group and the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation at day 7 of stay. The intragroup comparisons (p1, p2) were performed using the Wilcoxon test with Pratt correction (for dependent samples). The intergroup comparisons (p3, p4) were performed using the Mann—Whitney U test (for independent samples). In the intergroup comparison, the effect size is expressed in terms of the probability of superiority (PS), whereas in the intragroup comparison, it is expressed in terms of the rank-biserial correlation coefficient (rc). Abbreviation: TES — transcranial electrical stimulation.

Рис. 2. Значение медиан сывороточной концентрации интерлейкина-1β, 1‑е (первое измерение) и 7‑е (второе измерение) сутки госпитализации в исследуемых группах

Примечание: рисунок выполнен авторами. Обозначения уровней значимости: p1 — уровень значимости различий в группе ТЭС-терапии между 1-м и 7-м сутками (внутригрупповое сравнение); p2 — уровень значимости различий в группе сравнения между 1-м и 7-м сутками (внутригрупповое сравнение); p3 — уровень значимости различий между группами (ТЭС-терапия и сравнение) до начала лечения (1‑е сутки); p4 — уровень значимости различий между группами (ТЭС-терапия и сравнение) на 7‑е сутки госпитализации. Пояснение: Внутригрупповые сравнения (p1, p2) выполнены с помощью критерия Вилкоксона с поправкой Пратта (для зависимых выборок). Межгрупповые сравнения (p3, p4) — с помощью критерия Манна — Уитни (для независимых выборок). Размер эффекта при межгрупповом сравнении выражен через probability of superiority (PS), а при внутригрупповом — через ранговый бисериальный коэффициент корреляции (rc). Сокращения: TES — транскраниальная электростимуляция.

In the comparison group, the patients exhibited a statistically insignificant downward trend in the level of the specified indicator (Fig. 2; second measurement): from 1.7 (1.1; 2.9) pg/mL to 1.5 (0.9; 2.8) pg/mL (by 11.8%) (p = 0.7; effect size — rc = 0.09 [ 95% CI −0.4–0.6]) by day 7 of hospitalization.

In the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation, conversely, the IL-1β level reached 0.7 (0.1; 1.1) pg/mL by the time of the second measurement (Fig. 2), i.e., it decreased by 70.8% relative to the baseline (2.4 (1.0; 3.7) pg/mL) (p = 0.007; effect size — rc = 0.8 (95% CI 0.4–1)). By the end of the observation period, the TES therapy group exhibited a 53.3% lower level of the analyzed indicator (1.5 (0.9; 2.8) pg/mL in the comparison group versus 0.7 (0.1; 1.1) pg/mL in TES therapy group) (p = 0.005; effect size — PS = 0.2 (95% CI 0.06–0.4)).

The administration of transcranial electrical stimulation was associated with a more pronounced decrease in the serum cytokine level, which apparently reflects the anti-inflammatory effect of this treatment method. Thus, IL-1β levels decreased in 12 out of 15 patients. The maximum value of this indicator in the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation amounted to 3.8 pg/mL by the time of the second measurement (with the baseline level of 12.3 pg/mL in this patient). In the comparison group, the maximum cytokine level was equal to 20.9 pg/mL (with the baseline level of 7.1 pg/mL in this patient). Among the three patients in the TES therapy group whose cytokine level increased, the maximum value during the second measurement amounted to 3.7 pg/mL.

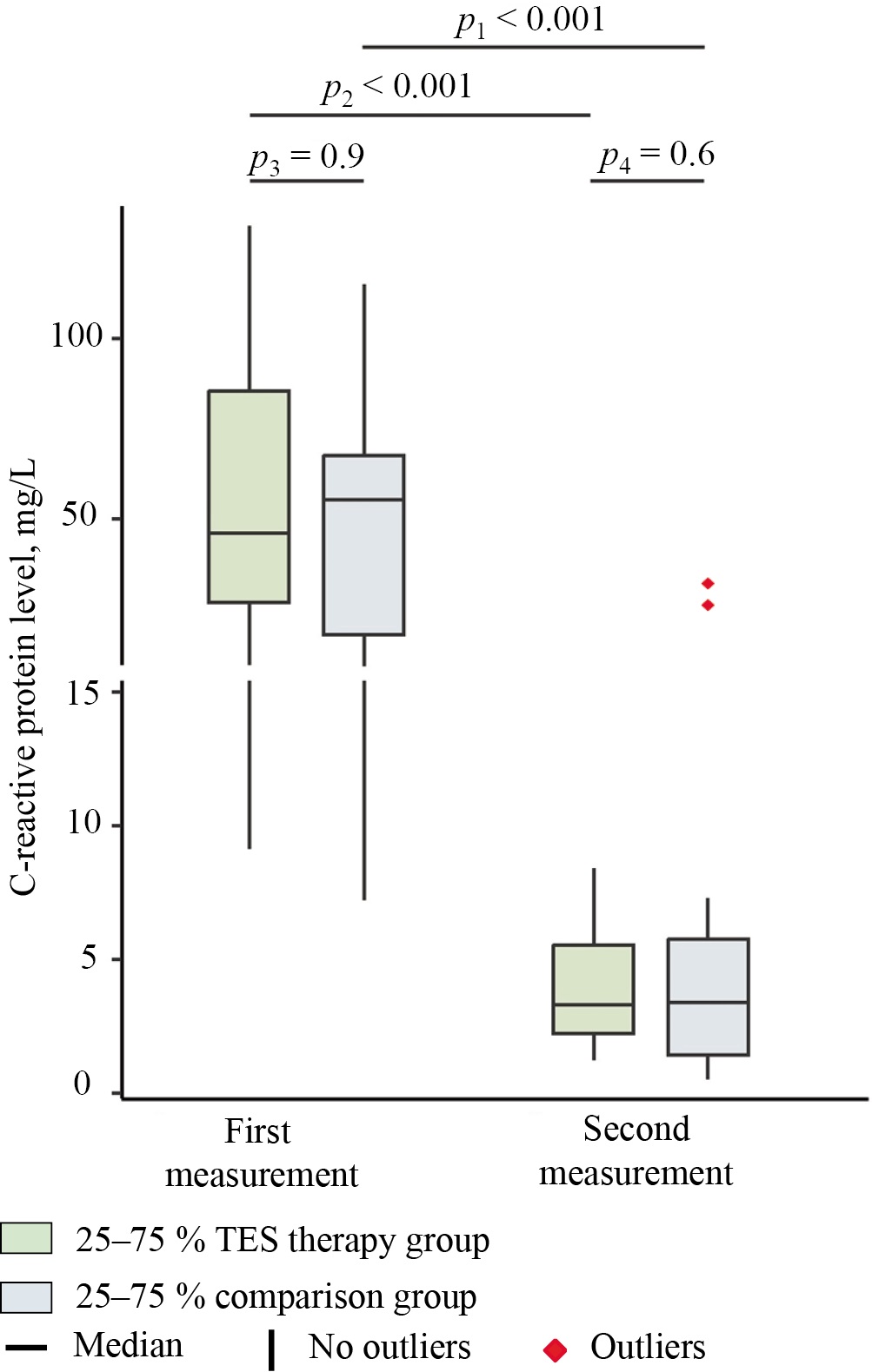

In the comparison group, the CRP level (Fig. 3) was equal to 55.2 (17.9; 67.6) mg/L prior to treatment, whereas in the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation, it reached 46.1 (26.7; 85.5) mg/L. At baseline, intergroup differences were statistically insignificant (p = 0.9; effect size — PS = 0.5; 95% CI 0.288–0.719). Thus, both groups of patients exhibited a markedly elevated CRP level against the standard reference range of 0–5 mg/L6. Such hypersynthesis of acute phase proteins is characteristic of COVID-19 and is widely used as an indicator of inflammation severity and the need for therapy adjustment and prognosis [21].

Fig. 3. Median serum levels of C-reactive protein in the study groups at days 1 (first measurement) and 7 (second measurement) of hospitalization

Note: The figure was created by the authors. Significance levels: p1 — significance level of differences between days 1 and 7 in the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation (intra-group comparison); p2 — significance level of differences between days 1 and 7 in the comparison group (intra-group comparison); p3 — significance level of differences between the comparison group and the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation before treatment (day 1); p4 — significance level of differences between the comparison group and the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation at day 7 of stay. The intragroup comparisons (p1, p2) were performed using the Wilcoxon test with Pratt correction (for dependent samples). The intergroup comparisons (p3, p4) were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test (for independent samples). In the intergroup comparison, the effect size is expressed in terms of the probability of superiority (PS), whereas in the intragroup comparison, it is expressed in terms of the rank-biserial correlation coefficient (rc). Abbreviation: TES — transcranial electrical stimulation.

Рис. 3. Значение медиан концентрации С-реактивного белка, 1‑е (первое измерение) и 7‑е сутки (второе измерение) госпитализации в исследуемых группах

Примечание: рисунок выполнен авторами. Обозначения уровней значимости: p1 — уровень значимости различий в группе ТЭС-терапии между 1-м и 7-м сутками (внутригрупповое сравнение); p2 — уровень значимости различий в группе сравнения между 1-м и 7-м сутками (внутригрупповое сравнение); p3 — уровень значимости различий между группами (ТЭС-терапия и сравнение) до начала лечения (1‑е сутки); p4 — уровень значимости различий между группами (ТЭС-терапия и сравнение) на 7‑е сутки госпитализации. Пояснение: Внутригрупповые сравнения (p1, p2) выполнены с помощью критерия Вилкоксона с поправкой Пратта (для зависимых выборок). Межгрупповые сравнения (p3, p4) — с помощью критерия Манна — Уитни (для независимых выборок). Размер эффекта при межгрупповом сравнении выражен через probability of superiority (PS), а при внутригрупповом — через ранговый бисериальный коэффициент корреляции (rc). Сокращения: TES — транскраниальная электростимуляция.

By the time of the second measurement, the comparison group showed a CRP level of 3.4 (1.5; 5.7) mg/L, which corresponds to a 93.8% decrease in this marker relative to the baseline value (55.2 (17.9; 67.6) mg/L) (p = 0.0003; effect size — rc = 0.95; 95% CI 0.8–1). In the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation, the CRP level was equal to 3.3 (2.2; 5.5) mg/L at day 7, which means a 92.8% decrease relative to the baseline level (46.1 (26.7; 85.5) mg/L) (p = 0.0006; effect size — rc = 1). At day 7, the intergroup comparison showed no statistically significant differences in the level of this inflammatory response marker (p = 0.6; PS = 0.5; 95% CI 0.3–0.7). All patients in the TES therapy group exhibited a positive change in this indicator. In the comparison group, a CRP decrease was recorded in 19 out of 20 patients; in one participant, the level of acute phase protein increased from 14.6 to 31 mg/L. The obtained results indicate a marked decrease in the inflammatory response intensity in both groups by day 7 of observation, which can be considered to be a favorable prognostic sign in COVID-19. Noteworthy is that literature data suggest the possibility of a secondary (late) CRP level peak occurring after the 11th day of the disease, which may complicate severity assessment, as well as the selection of the optimal treatment strategy [21].

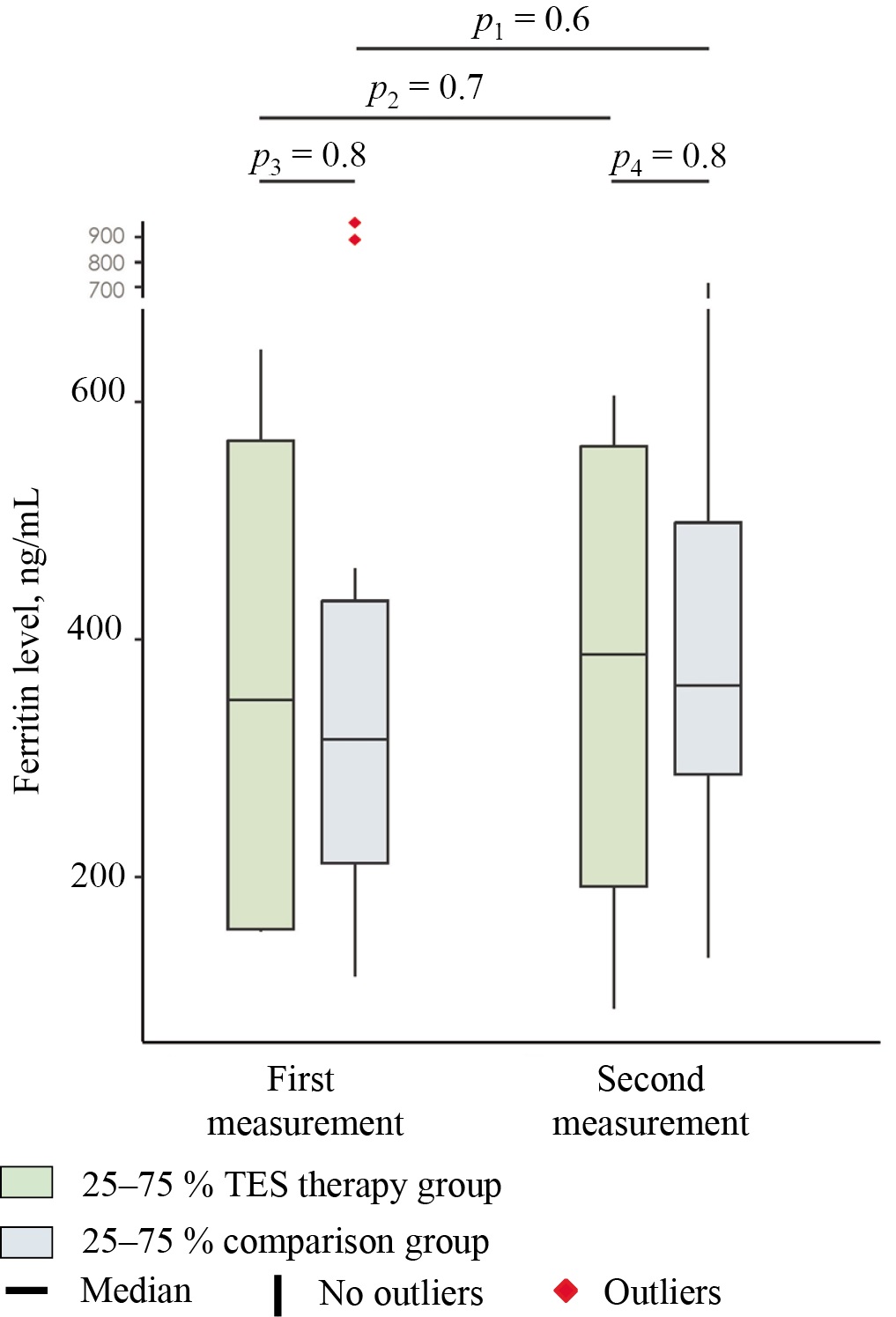

In the comparison group, the pre-treatment ferritin level (Fig. 4) was equal to 316 (212.3; 433) ng/mL. In the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation, this indicator was comparable, amounting to 349.8 (156.4; 567.9) ng/mL. The intergroup comparison revealed no statistically significant differences before treatment (p = 0.8; PS = 0.45). Noteworthy is that in both groups, the ferritin levels were elevated relative to reference values (21.8–274.6 ng/mL7). An elevated ferritin level is widely regarded in the literature as a significant diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for COVID-19 [22]. Hyperferritinemia is associated with a combination of pathological processes induced by the infection: increased ferritin synthesis by hepatocytes in response to proinflammatory cytokines (primarily IL-6) and at least two additional mechanisms, which will be discussed in detail below.

Fig. 4. Median serum levels of ferritin in the study groups at days 1 (first measurement) and 7 (second measurement) of hospitalization

Note: The figure was created by the authors. Significance levels: p1 — significance level of differences between days 1 and 7 in the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation (intra-group comparison); p2 — significance level of differences between days 1 and 7 in the comparison group (intra-group comparison); p3 — significance level of differences between the comparison group and the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation before treatment (day 1); p4 — significance level of differences between the comparison group and the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation at day 7 of stay. The intragroup comparisons (p1, p2) were performed using the Wilcoxon test with Pratt correction (for dependent samples). The intergroup comparisons (p3, p4) were performed using the Mann–Whitney U test (for independent samples). In the intergroup comparison, the effect size is expressed in terms of the probability of superiority (PS), whereas in the intragroup comparison, it is expressed in terms of the rank-biserial correlation coefficient (rc). Abbreviation: TES — transcranial electrical stimulation.

Рис. 4. Значение медиан концентрации ферритина, 1‑е (первое измерение) и 7‑е сутки (второе измерение) госпитализации в исследуемых группах.

Примечание: рисунок выполнен авторами. Обозначения уровней значимости: p1 — уровень значимости различий в группе ТЭС-терапии между 1-м и 7-м сутками (внутригрупповое сравнение); p2 — уровень значимости различий в группе сравнения между 1-м и 7-м сутками (внутригрупповое сравнение); p3 — уровень значимости различий между группами (ТЭС-терапия и сравнение) до начала лечения (1‑е сутки); p4 — уровень значимости различий между группами (ТЭС-терапия и сравнение) на 7‑е сутки госпитализации. Пояснение: Внутригрупповые сравнения (p1, p2) выполнены с помощью критерия Вилкоксона с поправкой Пратта (для зависимых выборок). Межгрупповые сравнения (p3, p4) — с помощью критерия Манна — Уитни (для независимых выборок). Размер эффекта при межгрупповом сравнении выражен через probability of superiority (PS), а при внутригрупповом — через ранговый бисериальный коэффициент корреляции (rc). Сокращения: TES — транскраниальная электростимуляция.

The second measurement yielded a ferritin level of 361.5 (286.7; 498.4) ng/mL in the comparison group. As compared to the baseline level, the median value increased by 14.4% (baseline level — 316 (212.3; 433) ng/mL); however, the changes were statistically insignificant (p = 0.6; rc = 0.2). In the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation, this indicator also increased and amounted to 387.9 (192.5; 563) ng/mL. The median increase by the end of the first week was equal to 10.9% (baseline level — 349.8 (156.4; 567.9) ng/mL) and was also statistically insignificant (p = 0.7; rc = 0.2). At this point in time, the intergroup comparison revealed no statistically significant differences in the ferritin (p = 0.8; PS = 0.45).

Unlike the CRP level, the ferritin level increased in a significant proportion of patients by the end of the first week of treatment in both the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation and the comparison group. These results may indirectly indicate the pathogenetic significance of iron metabolism disorders and cytolysis processes (see discussion below), whose dynamics are not necessarily synchronized with the inflammatory response.

Thus, the combination of transcranial electrical stimulation with the standard treatment of the disease caused no increase in the IL-1β level, did not provoke cytokine release syndrome (Fig. 2), and did not exacerbate the laboratory manifestations of the acute phase response (see Table). The standard therapy, which did not include targeted anti-cytokine therapy, had little effect on the IL-1β level (Fig. 2). In the standard treatment group, the patients exhibited a decrease in the level of CRP but not in ferritin. Conversely, the combination of transcranial electrical stimulation with the standard therapy had a significant effect on the IL-1β level, which exceeded 3 pg/mL only in one patient in this group by the end of the observation period (Fig. 2).

Additional study results

No additional results were obtained during the study.

Adverse events

No lethal cases were reported in either group. No adverse events associated with the use of transcranial electrical stimulation were observed.

DISCUSSION

Summary of the main study result

In this study, the patients receiving the standard therapy (without targeted anti-cytokine drugs) showed no statistically significant decrease in the IL-1β level during the observation period. Conversely, the TES therapy group showed a marked decrease in the serum IL-1β level, with administration of TES therapy causing no complications in the COVID-19 patients. Both groups exhibited a significant decrease in the CRP levels, while no positive changes were observed in the ferritin levels.

Discussion of the main study result

Cytokine hyperproduction lies at the heart of cytokine release syndrome in the considered disease [1]. This phenomenon adversely affects the patient’s prognosis and requires a search for treatment methods. Among the key proinflammatory cytokines, of note is IL-1β, which plays a pivotal role in the development of a maladaptive immune response. Laboratory studies confirmed the ability of the SARS-CoV-2 virus to induce inflammasome assembly responsible for the partial proteolysis of pro-IL-1β (by the enzyme caspase-1) to active IL-1β (as well as pro-IL-18 to IL-18), which leads to its hyperproduction [2][3]. The mechanism seems to involve the direct activation of functionally related proteins (NLRP3, TRAF3, and ASC) by viral proteins (nucleocapsid protein (N) and Orf3a viroporin) [2][28]. In addition to immune response amplification, the described processes produce other cytopathic effects. An important example is the activation of gasdermin D (GSDMD) that increases cell membrane permeability, a central event in the pathogenesis of programmed cell death by pyroptosis [2]. The latter further exacerbates life-threatening multi-organ failure. Also, cell disruption is associated with the release of tissue thromboplastin and the initiation of coagulation cascades. Furthermore, IL-1β contributes to thromboinflammation in a variety of other ways: it promotes megakaryocyte maturation, platelet adhesion, and the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (which, in turn, leads to the Hageman factor autoactivation and suppresses antithrombin and tissue factor pathway inhibitor), as well as affecting the endothelium [3][29]. The latter factor is particularly important since activated endothelium becomes a source of cytokines, eicosanoids, free radicals, and proaggregatory/procoagulant substances (von Willebrand factor), while the production of anticoagulants (thrombomodulin) declines [3]. In addition, endothelial cells strongly express adhesion molecules (P-selectins, intercellular adhesion molecules, and vascular cell adhesion molecules), to which leukocyte surface proteins attach, leading to the activation of the latter [1][3].

Hyperproduction of IL-1β (along with TNF and IL-6) constitutes one of the main mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of acute phase response, which includes a range of systemic effects of inflammation (fever, synthesis of acute-phase proteins/peptides, systemic iron metabolism reorganization, stimulation of leukopoiesis and stress-induced splenic erythropoiesis, postreceptor inhibition of insulin signal transduction, etc.) [1][30]. Extremely high levels of these cytokines have a direct cytopathic systemic effect on vital organs, further contributing to multiple organ failure. A special related problem is secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (macrophage activation syndrome), which results in a cytokine storm and additional organ damage [1].

Ferritin and CRP belong to acute-phase proteins; their production by the liver is stimulated by proinflammatory cytokines (especially IL-6) [1][21][22]. Ferritin is also a key participant in systemic iron metabolism. During inflammation, this metabolism is disrupted depending on the severity of the disease, which is pathogenetically associated with an imbalance of regulatory substances (hepcidin, erythroferone, bone morphogenetic protein 6, and growth differentiation factor 15), the direct effect of cytokines on the red bone marrow, and systemic dysfunction of CD163-positive cells of the phagocytic mononuclear system [22][30–32]. The latter are also a source of hyperferritinemia during inflammation. Finally, ferritin present in cells deposits iron; therefore, during cytolysis, an increase in the extracellular protein level is observed [22]. Cytolysis, in turn, can be caused by respiratory or ischemic (e.g., due to thrombosis) tissue hypoxia, as well as the cytopathic effects of the virus, inflammatory mediators, and other substances (e.g., catecholamines in the context of an adrenergic/sympathetic storm) in COVID-19 [33]. Thus, at least three mechanisms behind a ferritin level increase due to inflammation can be identified.

In the present study, the standard treatment, which includes glucocorticoid therapy without targeted anti-cytokine drugs, had no effect on the serum IL-1β and ferritin levels. Similar results were reported in other studies. For example, Alonso-Domínguez et al. (2023) showed that the levels of IL-1β, TNF, and macrophage inflammatory protein 1α (MIP-1α) can remain elevated one month after the onset of infection [28]. Moreover, this trend observed only in these three indicators but not the others in the long list under study—IL-3, IL-6, IL-8, IL-18, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), IFN-γ induced protein 10, IFN-γ induced monokine, and MIP 1β—is associated with the risk of long-term consequences of infection and long COVID-19. As the predictive threshold level, Alonso-Domínguez et al. (2023) offer an IL-1β level of over 7.36 pg/mL. In this case, the prognostic value of this indicator is higher than that of the TNF and MIP-1α levels: the area under the characteristic curve of 0.709 versus 0.682 and 0.691, respectively [28].

As we have shown in this study, the comparison group patients experienced a marked decrease in the CRP level by the end of the observation period, which can probably be attributed to the successful elimination of the pathogen by the immune system and the effect of treatment. The differences between CRP and IL-1β level dynamics can be speculatively explained by the pivotal role of IL-6 in stimulating the synthesis of acute phase proteins. Of interest is the study of how IL-6 level dynamics correlate with changes in the CRP and IL-1β levels. We also hypothesize that CRP cannot serve as a laboratory indication of IL-1β dysfunction (although the clinical significance of this is unclear). As mentioned above, the ferritin level is affected by a combination of pathological processes. In this context, it would be interesting to compare the dynamics of this indicator with changes in the IL-6 level (in order to assess the contribution of acute phase response to the development of hyperferritinemia) and cytolysis markers, for example, aminotransferases.

The combination of TES therapy with the standard treatment resulted in a marked decrease in the IL-1β level (Fig. 2). In this group, all patients with the initially high cytokine level exhibited a pronounced decrease by the end of the first week. Only several patients with the initially low IL-1β level showed a slight increase, which did not exceed 1.2 pg/mL. As well as in the comparison group, the patients exhibited a marked decrease in the CRP but not in the ferritin level. Transcranial electrical stimulation caused no serious complications, specifically cytokine release syndrome. Such results pathogenetically justify further study of this treatment method in COVID-19.

The obtained data are consistent with previous studies demonstrating the effect of the TEP therapy on neuroimmunoendocrine dysregulation in animal experiments and in clinical practice. This effect was studied in the context of various pathologies, with some of the studies addressing the effect of TES therapy on IL-1β production. In particular, this method was shown to have a positive effect on cytokine levels in animals under simulated conditions of severe combined stress, acute cerebrovascular accidents, etc. [19][34]. Clinical studies revealed the ability of TES therapy to reduce the IL-1β level in patients with coronary artery disease and acute pancreatitis, as well as during rehabilitation after treatment for malignant neoplasms [18][20].

This effect is believed to be attributed primarily to the activation of the body’s antinociceptive systems: opioidergic (stimulation of β-endorphin production), dopaminergic, and serotonergic [35][36]. However, the functions of these systems go far beyond pain suppression and include, for example, stress-limiting effects and regulation of energy metabolism, immunity, and oxidative status [7][37]. Transcranial electrical stimulation promotes endogenous β-endorphin production and inhibits the hyperproduction of proinflammatory mediators, as shown by this and a number of previous studies.

Research limitations

The number of participants was small. The study has a pathophysiological focus, so, in accordance with the defined aims, clinical parameters were not considered. Therefore, the clinical significance of the IL-1β level decrease in the group receiving transcranial electrical stimulation is unclear (especially considering the trials of targeted IL-1β blocking drugs) [38][39].

CONCLUSION

TES therapy was found to reduce the serum IL-1β level in moderate COVID-19 patients who did not receive targeted anti-cytokine treatment. The CRP and ferritin level dynamics in the patients who received TES therapy in addition to the standard treatment showed no statistically significant differences from those in the comparison group.

1 Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Interim Guidelines: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Version 11 (May 7, 2021). Available: https://static-0.minzdrav.gov.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/055/735/original/B%D0%9C%D0%A0_COVID-19.pdf

Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Interim Guidelines: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Version 12 (September 21, 2021). Available: https://static-0.minzdrav.gov.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/058/075/original/%D0%92%D0%9C%D0%A0_COVID-19_V12.pdf

Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Interim Guidelines: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Version 13 (October 14, 2021). Available: https://static-0.minzdrav.gov.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/058/211/original/BMP-13.pdf

Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Interim Guidelines: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Version 14 (December 27, 2021). Available: https://static-0.minzdrav.gov.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/059/041/original/%D0%92%D0%9C%D0%A0_COVID-19_V14_27-12-2021.pdf

Ministry of Health of the Russian Federation. Interim Guidelines: Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of the Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19). Version 15 (February 22, 2022). Available: https://static-0.minzdrav.gov.ru/system/attachments/attaches/000/059/392/original/%D0%92%D0%9C%D0%A0_COVID-19_V15.pdf

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

4 R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2024 Available: https://www.R-project.org/

5 Mangiafico S. rcompanion: Functions to Support Extension Education Program Evaluation. version 2.4.36. Rutgers Cooperative Extension. New Brunswick, New Jersey. 2024. Available: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rcompanion

6 Reference values established by the laboratory of the Regional Clinical Hospital No. 2, Ministry of Health of Krasnodar Krai

7 Ibid.

References

1. Darif D, Hammi I, Kihel A, El Idrissi Saik I, Guessous F, Akarid K. The pro-inflammatory cytokines in COVID-19 pathogenesis: What goes wrong? Microb Pathog. 2021;153:104799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2021.104799

2. Bittner Z.A., Schrader M., George S.E., Amann R. Pyroptosis and Its Role in SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Cells. 2022;11(10):1717. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells11101717

3. Potere N, Abbate A, Kanthi Y, Carrier M, Toldo S, Porreca E, Di Nisio M. Inflammasome Signaling, Thromboinflammation, and Venous Thromboembolism. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2023;8(9):1245–1261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2023.03.017

4. Moreno-Duarte I, Gebodh N, Schestatsky P, Guleyupoglu B, Reato D, Bikson M, Fregni F. Transcranial Electrical Stimulation: Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation (tDCS), Transcranial Alternating Current Stimulation (tACS), Transcranial Pulsed Current Stimulation (tPCS), and Transcranial Random Noise Stimulation (tRNS). In: Cohen Kadosh R., editor. The Stimulated Brain: сognitive Enhancement Using Non-Invasive Brain Stimulation. 2014;35–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-404704-4.00002-8

5. Shen Y, Liu J, Zhang X, Wu Q, Lou H. Experimental study of transcranial pulsed current stimulation on relieving athlete’s mental fatigue. Front Psychol. 2022;13:957582. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.957582

6. Tarasova DN, Skvortsov VV, Levitan BN. Transcranial electrical stimulation in the treatment of peptic ulcer. Lechaschi Vrach. 2024;2(27):21– 24 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.51793/OS.2024.27.2.004

7. Kade AKh, Kazanchi DN, Polyakov PP, Zanin SA, Gavrikova PA, Katani ZO, Chernysh KM. Hypercatecholaminaemia in stress urinary incontinence and its pathogenetic treatment perspectives: an experimental non-randomised study. Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2022;29(2):118–130 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2022-29-2-118-130

8. Zanin SA, Chabanets EA, Kade AKh, Polyakov PP, Trofimenko AI, Zanina ES. Adiponectin as the main representative of adipokines: role in pathology, possibilities of TES-therapy. Medical news of the north Caucasus. 2022;17(4):455–461 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.14300/mnnc.2022.17110

9. Pinto TP, Inácio JC, de Aguiar E, Ferreira AS, Sudo FK, Tovar-Moll F, Rodrigues EC. Prefrontal tDCS modulates autonomic responses in COVID-19 inpatients. Brain Stimul. 2023:16(2):657–666. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2023.03.001

10. Andrade SM, Cecília de Araújo Silvestre M, Tenório de França EÉ, Bezerra Sales Queiroz MH, de Jesus Santana K, Lima Holmes Madruga ML, Torres Teixeira Mendes CK, Araújo de Oliveira E, Bezerra JF, Barreto RG, Alves Fernandes da Silva SM, Alves de Sousa T, Medeiros de Sousa WC, Patrícia da Silva M, Cintra Ribeiro VM, Lucena P, Beltrammi D, Catharino RR, Caparelli-Dáquer E, Hampstead BM, Datta A, Teixeira AL, Fernández-Calvo B, Sato JR, Bikson M. Efficacy and safety of HD-tDCS and respiratory rehabilitation for critically ill patients with COVID-19 The HD-RECOVERY randomized clinical trial. Brain Stimul. 2022;15(3):780–788. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2022.05.006

11. Fawzy NA, Abou Shaar B, Taha RM, Arabi TZ, Sabbah BN, Alkodaymi MS, Omrani OA, Makhzoum T, Almahfoudh NE, Al-Hammad QA, Hejazi W, Obeidat Y, Osman N, Al-Kattan KM, Berbari EF, Tleyjeh IM. A systematic review of trials currently investigating therapeutic modalities for post-acute COVID-19 syndrome and registered on WHO International Clinical Trials Platform. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2023;29(5):570–577. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2023.01.007.

12. Nesina I.A., Golovko EA, Shakula AV, Figurenko NN, Zhilina IG, Khomchenko TN, Smirnova EL, Chursina VS, Koroleva AV. Experience of Outpatient Rehabilitation of Patients after Pneumonia Associated with the New Coronavirus Infection COVID-19. Bulletin of Rehabilitation Medicine. 2021;20(5):4–11 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.38025/2078-1962-2021-20-5-4-11

13. Pilloni G, Bikson M, Badran BW, George MS, Kautz SA, Okano AH, Baptista AF, Charvet LE. Update on the Use of Transcranial Electrical Brain Stimulation to Manage Acute and Chronic COVID-19 Symptoms. Front Hum Neurosci. 2020;14:595567. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2020.595567

14. Alharthy A, Faqihi F, Memish ZA, Karakitsos D. Lung Injury in COVID-19-An Emerging Hypothesis. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11(15):2156–2158. https://doi.org/10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00422

15. Finsterer J. Neurological Perspectives of Neurogenic Pulmonary Edema.Eur Neurol. 2019;81(1-2):94–102. https://doi.org/10.1159/000500139

16. Angelini P, Postalian A, Hernandez-Vila E, Uribe C, Costello B. COVID-19 and the Heart: Could Transient Takotsubo Cardiomyopathy Be Related to the Pandemic by Incidence and Mechanisms? Front Cardiovasc Med. 2022;9:919715. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2022.919715.

17. Kade AKh, Kravchenko SV, Trofimenko AI, Chaplygina KYu, Ananeva EI, Poliakov PP, Lipatova AS. The efficacy of TES-therapy for treatment of anxiety-like behavior and motor disorders in rats with an experimental model of parkinsonism. S.S. Korsakov Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry 2019;119(9):91–96 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17116/jnevro201911909191

18. Penzhoyan AG, Penzhoyan GA, Akhedzhak-Naguze SK, Abushkevich VG, Burlutskaya AV. Increasing stress resistance by transcranial electrical stimulation in patients after prostate cancer surgery. Ul’yanovskiy mediko-biologicheskiy zhurnal. 2022;1:75–96 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.34014/2227-1848-2022-1-75-86

19. Lipatova AS, Kade AKh, Trofimenko AI, Polyakov PP Correction of stress-induced neuromimuneendocrine disturbances in male rats with low stress sustainability by transcranial direct current stimulation. Kursk Scientific and Practical Bulletin «Man and His Health». 2018;3:58–68 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.21626/vestnik/2018-3/09

20. Klindukhova MO, Kade AK. Effect of transcranial electrical stimulation on the dynamics of interleukins in patients with acute pancreatitis. Journal of new medical technologies, eEdition. 2024;18(2):93–97 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.24412/2075-4094-2024-2-3-3

21. Bilalova AR, Moiseeva SV, Shakirova VG, Khaertynova IM, Gataullin MR, Sozinova YuM, Fatkullin BSh. Clinical and laboratory characteristics of patients with coronavirus infection. Practical medicine. 2023;21(1):30–37 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.32000/2072-1757-2023-1-30-37

22. Polushin YuS, Shlyk IV, Gavrilova EG, Parshin EV, Ginzburg AM. The Role of Ferritin in Assessing COVID-19 Severity. Messenger of anesthesiology and resuscitation. 2021;18(4):20–28 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.21292/2078-5658-2021-18-4-20-28

23. Xu S, Chen M, Feng T, Zhan L, Zhou L, Yu G. Use ggbreak to Effectively Utilize Plotting Space to Deal With Large Datasets and Outliers. Front Genet. 2021;12:774846. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2021.774846

24. Uanhoro JO. Probability of superiority for comparing two groups of clusters. Behav Res. 2023:55:646–656. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-022-01815-6

25. Hothorn T, Hornik K, van de Wiel MA, Zeileis A. Implementing a class of permutation tests: The coin package. J Stat Soft. 2008;28(8):1–23. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v028.i08

26. In J, Lee DK. Alternatives to the P value: connotations of significance. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2024;77(3):316–325. https://doi.org/10.4097/kja.23630

27. Ordak M. Multiple comparisons and effect size: Statistical recommendations for authors planning to submit an article to Allergy. Allergy. 2023;78(5):1145–1147. https://doi.org/10.1111/all.15700

28. Alonso-Domínguez J, Gallego-Rodríguez M, Martínez-Barros I, Calderón-Cruz B, Leiro-Fernández V, Pérez-González A, Poveda E. High Levels of IL-1β, TNF-α and MIP-1α One Month after the Onset of the Acute SARS-CoV-2 Infection, Predictors of Post COVID-19 in Hospitalized Patients. Microorganisms. 2023;11(10):2396. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms11102396

29. Nesterova IV, Atazhakhova MG, Teterin YuV, Matushkina VA, Chudilova GA, Mitropanova MN. The role of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in the immunopathogenesis of severe COVID-19: potential immunotherapeutic strategies regulating net formation and activity. Russian Journal of Infection and Immunity. 2023;13(1):9–28 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.15789/2220-7619-TRO-2058

30. Volfovitch Y, Tsur AM, Gurevitch M, Novick D, Rabinowitz R, Mandel M, Achiron A, Rubinstein M, Shoenfeld Y, Amital H. The intercorrelations between blood levels of ferritin, sCD163, and IL-18 in COVID-19 patients and their association to prognosis. Immunol Res. 2022;70(6):817–828. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12026-022-09312-w

31. Schmidtner N, Utrata A, Mester P, Schmid S, Müller M, Pavel V, Buechler C. Reduced Plasma Bone Morphogenetic Protein 6 Levels in Sepsis and Septic Shock Patients. Biomedicines. 2024;12(8):1682. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12081682

32. Rochette L, Zeller M, Cottin Y, Vergely C. GDF15: an emerging modulator of immunity and a strategy in COVID-19 in association with iron metabolism. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2021;32(11):875–889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tem.2021.08.011

33. Al-Kuraishy HM, Al-Gareeb AI, Mostafa-Hedeab G, Kasozi KI, Zirintunda G, Aslam A, Allahyani M, Welburn SC, Batiha GE. Effects of β-Blockers on the Sympathetic and Cytokines Storms in COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2021;12:749291. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2021.749291

34. Zanin SA, Kade AK, Trofimenko AI, Baykova EE, Onopriev VV The effect of transcranial electrical stimulation of brain endorphinergic mechanisms on the blood β-endorphin level in experimental ischemic stroke and traumatic brain injury. Annals of Clinical and Experimental Neurology. 2016;10(3):45–49 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17816/psaic43

35. Kravchenko SV, Kade AK, Vcherashnyuk SP, Polyakov PP, Bulatova VV, Mischenko AS The influence of transcranial electrical stimulation therapy on the dynamics of anxiety in rats with rotenoneinduced parkinsonism model. Modern problems of science and education. 2019;3:144 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17513/spno.28903

36. Kade AKh, Polyakov PP, Agumava AA, Gusaruk LR, Tsymbalov OV, Alimetov AY, Lipatova AS, Vcherashnyuk SP, Kravchenko SV, Sharkova AV, Chernykh NY, Belyakova IS. Transcranial electrotherapy stimulation modulates stress-induced c-fos expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in rats with different resistance to stress. Modern problems of science and education. 2018;1:65 (In Russ.). https://doi.org/10.17513/spno.27389

37. Pandey V, Yadav V, Singh R, Srivastava A, Subhashini. β-Endorphin (an endogenous opioid) inhibits inflammation, oxidative stress and apoptosis via Nrf-2 in asthmatic murine model. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):12414. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-38366-5

38. Davidson M, Menon S, Chaimani A, Evrenoglou T, Ghosn L, Graña C, Henschke N, Cogo E, Villanueva G, Ferrand G, Riveros C, Bonnet H, Kapp P, Moran C, Devane D, Meerpohl JJ, Rada G, Hróbjartsson A, Grasselli G, Tovey D, Ravaud P, Boutron I. Interleukin-1 blocking agents for treating COVID-19. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2022;1(1):CD015308. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD015308

39. Lan SH, Hsu CK, Chang SP., Lu LC, Lai CC Clinical efficacy and safety of interleukin-1 blockade in the treatment of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ann Med. 2023;55(1):2208872. https://doi.org/10.1080/07853890.2023.2208872

About the Authors

M. Yu. IgnatenkoRussian Federation

Marina Yu. Ignatenko — Postgraduate student, Department of General and Clinical Pathophysiology

Mitrofana Sedina str., 4, Krasnodar, 350063

E. V. Kochkarova

Russian Federation

Ekaterina V. Kochkarova — Teaching Assistant, Department of General and Clinical Pathophysiology

Mitrofana Sedina str., 4, Krasnodar, 350063

N. V. Izmaylova

Russian Federation

Nataliya V. Izmaylova — Biologist, Clinical Diagnostic Laboratory

Krasnykh Partizan str., 6, bldg. 2, Krasnodar, 350012

S. A. Zanin

Russian Federation

Sergey A. Zanin — Cand. Sci. (Med.), Assoc. Prof., Acting Head of the Department of General and Clinical Pathophysiology

Mitrofana Sedina str., 4, Krasnodar, 350063

Review

For citations:

Ignatenko M.Yu., Kochkarova E.V., Izmaylova N.V., Zanin S.A. Effect of transcranial electrical stimulation on serum interleukin-1β levels in COVID-19 patients: A randomized prospective study. Kuban Scientific Medical Bulletin. 2025;32(6):41-55. https://doi.org/10.25207/1608-6228-2025-32-6-41-55

JATS XML